L'huomo di lettere

L'huomo di lettere difeso ed emendato (Rome, 1645) by the Ferrarese Jesuit Daniello Bartoli (1608-1685) is a two-part treatise on the man of letters bringing together material he had assembled as a teacher of rhetoric and a preacher. His literary success with this work led to his appointmernt in Rome as the official historiographer of the Society of Jesus.

Part I defends his high status under two headings, La Sapienza felice anche nelle Miserie and L'Ignoranza misera anche nelle Felicita. Part II emends his faults, taking particular aim at excesses of the precious baroque style then in vogue. Its chapters are Ladroneccio, Lascivia, Maldicenza, Alterezza, Dapoccaggine, Imprudenza, Ambitione, Avarizia, Oscurita.

Italian

In 1645 the appearance of Bartoli's first book initiated an international literary sensation.[1] The work quickly inserted itself in the regional literary debates of the time, with an unauthorized Florentine edition (1645) dedicated to Salvator Rosa soon challenged by a Bolognese edition (1646) dedicated to Virgilio Malvezzi. Over the following three decades and beyond there were another thirty printings at a dozen different Italian presses, especially Venetian, of which half a dozen "per Giunti, e Baba" with a signature frontispiece title illustration.(Here right)

Bartoli's literary "how to" book spread its influence well beyond the geographical and literary confines of Italy. During the process of her conversion to Roman Catholicism at the hands of the Jesuits in 1651 Christina, Queen of Sweden specifically requested a copy of this celebrated work be sent to her in Stockholm.[2] It seems to have fulfilled the Baroque dream of an energetic rhetorical eloquence to which the age aspired. Through its gallery of exemplary stylizations and picturesque moral encouragements it defends and emends not only the aspiring letterato, but also an updated classicism open to modernity, but diffident of excess. The book's international proliferation made it a vehicle of the cultural ascendancy of the Jesuits as modern classicists during the Baroque. Years later, Bartoli provided a revision for the collected edition.[3] After Bartoli's death the editions and translations continued to appear, particularly in the Ottocento.

In Bartoli's lifetime and beyond his work was also translated extensively, by men of letters of other nationalities, Jesuits and non-Jesuits.

French

The French translation by Thomas LeBlanc, S.J. first appeared in 1651 as L'Homme de lettres (Pont-a-Mousson). In 1654 it was reprinted under the more galant title, La Guide des Beaux Esprits. The fifth edition of 1669 was dedicated to Charles Le Jay, Baron de Tilly.[4] In the next century there was a second translation as L'homme de lettres by the Barnabite writer, T. Delivoy: (Paris: Herissant, 1769).

German

There was a German translation without Bartoli's name by Georg Adam von Kufstein (1605-1656) of the Weimar language academy Fruitbearing Society (Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft) (Nurnberg, 1654).[5]

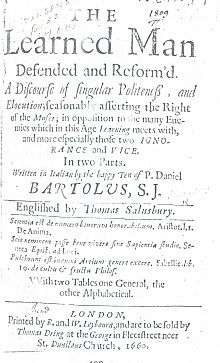

English

The London edition of 1660 celebrating the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy and dedicated to two of its chief protagonists George Monck and William Prynne, was translated under the name of Thomas Salusbury by the English Jesuit Thomas Plowden.[6] It was printed by the mathematician and surveyor William Leybourn and distributed by Thomas Dring, an important London bookseller.

Latin

The French Jesuit Louis Janin, who provided Latin translations of Bartoli's Istoria della Compagnia di Gesu, also furnished a Latin translation that was first printed in Lyons (1672) and then served as a scholastic edition brought out in Cologne in 1674 "opusculum docentibus atque ac discentibus utile ac necessarium".[7] To this was added a second translation into Latin by Johann Georg Hoffmann for the German world.[8]

Spanish

A Spanish version by the noted priest musician Gaspar Sanz appeared in Madrid (1678) and was reprinted in Barcelona (1744).[9]

Dutch

The Mennonite patriarch, Lambert Bidloo (1638-1724), an apothecary like Bartoli's father, was the brother of Govert Bidloo and father of Nicolaas Bidloo. He undertook a translation of this Baroque touchstone in his old age. This remarkable Dutch translation, accompanied by a host of poetical compositions by literary contemporaries, appeared in Amsterdam in 1722.[10]

References, Translations and Online Links

- ↑ Dell'Huomo di lettere difeso et emendato :Titlepage above

- ↑ John J. Renaldo, Daniello Bartoli: A letterato of the Seicento (Naples,1979) p. 41

- ↑ Delle opere del p. Daniello Bartoli, Le Morali (Rome: Varese, 1684)

- ↑ La Guide des Beaux Esprits

- ↑ Vertheidigung der Kunstlebenden und Gelehrten anstandigere Sitten

- ↑ The Learned Man Defended and Reform'd: A Discourse of Singular Politeness and Elocution asserting the Right of the Muses

- ↑ Character Hominis Literati

- ↑ Homo literatus defensus et emendatus (Frankfurt: Schrei, 1693)

- ↑ El Hombre de Letras

- ↑ Een Gelettererd Man Verdadigd, en Verbeterd door Daniel Bartholi