Pietà

The Pietà (Italian pronunciation: [pjeˈta]) is a subject in Christian art depicting the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus, most often found in sculpture. As such, it is a particular form of the Lamentation of Christ, a scene from the Passion of Christ found in cycles of the Life of Christ. When Christ and the Virgin are surrounded by other figures from the New Testament, the subject is strictly called a Lamentation in English, although Pietà is often used for this as well, and is the normal term in Italian.

Context and development

Pietà is one of the three common artistic representations of a sorrowful Virgin Mary, the other two being Mater Dolorosa (Mother of Sorrows) and Stabat Mater (here stands the mother).[1][2] The other two representations are most commonly found in paintings, rather than sculpture, although combined forms exist.[3]

.jpg)

The Pietà developed in Germany (where it is called the "Vesperbild") about 1300, reached Italy about 1400, and was especially popular in Central European Andachtsbilder.[4] Many German and Polish 15th-century examples in wood greatly emphasise Christ's wounds. The Deposition of Christ and the Lamentation or Pietà form the 13th of the Stations of the Cross, as well as one of the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin.

Although the Pietà most often shows the Virgin Mary holding Jesus, there are other compositions, including those where God the Father participates in holding Jesus (see gallery below). In Spain the Virgin often holds up one or both hands, sometimes with Christ's body slumped to the floor.

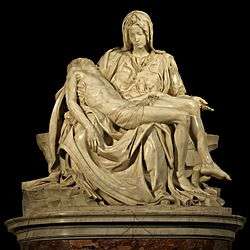

Michelangelo

A famous example by Michelangelo is located in St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican City. The body of Christ is different from most earlier pietà statues, which were usually smaller and in wood. The Virgin is also unusually youthful, and in repose, rather than the older, sorrowing Mary of most pietàs. She is shown as youthful for two reasons; God is the source of all beauty and she is one of the closest to God, also the exterior is thought as the revelation of the interior (the virgin is morally beautiful). The Pietà with the Virgin Mary is also unique among Michelangelo's sculptures, because it was the only one he ever signed, upon hearing that visitors thought it had been sculpted by Cristoforo Solari, a competitor.[5] Michelangelo's signature is carved into the sash the Virgin wears on her breast.

Michelangelo's last work was another Pietà, this one featuring not the Virgin Mary holding Christ, but rather Joseph of Arimathea, probably carved as a self-portrait. A generation later, the Spanish painter Luis de Morales painted a number of highly emotional Pietàs, with examples in the Louvre and Museo del Prado.

Gallery

Statues

Bohemian Pietà, 1390-1400

Bohemian Pietà, 1390-1400- Austrian Pietà, c. 1420

15th-century German wood Pietà from Cologne

15th-century German wood Pietà from Cologne Swabian painted wood Pietà of c. 1500

Swabian painted wood Pietà of c. 1500 Pietà by Michelangelo, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence

Pietà by Michelangelo, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence- Pieta near the base of the Our Lady of Lebanon statue, Harissa

- 18th-century Bavarian example with Rococo setting

- The Pietà of St. Patrick's Cathedral

- The Pietà: plaster of Michele Tripisciano in Caltanissetta (1913)

- Mother and Son by Joseph Whitehead, Woodside Cemetery, Paisley

Paintings

Pietà in frescoes found in the Church of St. Panteleimon, Gorno Nerezi, 1164

Pietà in frescoes found in the Church of St. Panteleimon, Gorno Nerezi, 1164 Pietà with God Father, Jean Malouel, Louvre, 1400-1410

Pietà with God Father, Jean Malouel, Louvre, 1400-1410 Kraków, c. 1450

Kraków, c. 1450.jpg) The Avignon Pietà, Enguerrand Charonton, 15th century

The Avignon Pietà, Enguerrand Charonton, 15th century.jpg) The prayer Obsecro te (1470s), from the Book of Hours of Angers

The prayer Obsecro te (1470s), from the Book of Hours of Angers

Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

Luis de Morales, 16th century

Luis de Morales, 16th century El Greco, Pietà, 1571-1576, Philadelphia Museum of Art

El Greco, Pietà, 1571-1576, Philadelphia Museum of Art_-_Pieta_(1876).jpg) William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Pietà, 1876, Dallas Museum of Fine Arts

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Pietà, 1876, Dallas Museum of Fine Arts

See also

References

- ↑ Arthur de Bles, 2004 How to Distinguish the Saints in Art by Their Costumes, Symbols and Attributes ISBN 1-4179-0870-X page 35

- ↑ Anna Jameson, 2006 Legends of the Madonna: as represented in the fine arts ISBN 1-4286-3499-1 page 37

- ↑ E.g. see Noël Quillerier's at Oratorio della Nunziatella

- ↑ G Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II,1972 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, pp. 179-181, figs 622-39, ISBN 0-85331-324-5

- ↑ William E. Wallace, 1995 Life and Early Works (Michelangelo: Selected Scholarship in English) ISBN 0-8153-1823-5 page 233

Further reading

- Forsyth, William F. (1995). The Pietà in French late Gothic sculpture: regional variations. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-681-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pietà. |

- Michelangelo's Pieta in St Peter's Basilica

- Data collection of the image type Pietà in sculpture

- 3D model of a detail of Mary from a cast made by the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the Vatican Museums, via photogrammetric survey

- Poem by Moez Surani proposing nine new sculptural pietas