Le Chat Noir

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Le Chat Noir (French pronunciation: [lə ʃa nwaʁ]; French for "The Black Cat") was a nineteenth-century entertainment establishment, in the bohemian Montmartre district of Paris. It opened on 18 November 1881 at 84 Boulevard de Rochechouart by the impresario Rodolphe Salis, and closed in 1897 not long after Salis' death (much to the disappointment of Picasso and others who looked for it when they came to Paris for the Exposition in 1900).

Le Chat Noir is thought to be the first modern cabaret:[1] a nightclub where the patrons sat at tables and drank alcoholic beverages while being entertained by a variety show on stage. The acts were introduced by a master of ceremonies who interacted with well-known patrons at the tables. Its imitators have included cabarets from St. Petersburg (Stray Dog Café) to Barcelona (Els Quatre Gats).

Perhaps best known now by its iconic Théophile Steinlen poster art, in its heyday it was a bustling nightclub that was part artist salon, part rowdy music hall. The cabaret published its own humorous journal Le Chat Noir until 1895.

Early history

The cabaret began by renting the cheapest accommodations it could find, a small two-room site located at 84 Boulevard Rochechouart, (now commemorated only by a historical plaque). Its success was assured with the wholesale arrival of a group of radical young writers and artists called Les Hydropathes ("those who are afraid of water — so they drink only wine"), a club led by the journalist Émile Goudeau. The group claimed to be averse to water, preferring wine and beer. Their name doubled as a nod to the "rabid" zeal with which they advocated their sociopolitical and aesthetic agendas. Goudeau’s club met in his house on the Rive Gauche (left bank), but had become so popular that it outgrew its meeting place. Salis met Goudeau, whom he convinced to relocate the club meeting place across the river to 84 Boulevard Rochechouart.[2]

The cabaret began by serving bad wine and had a rather inferior decor, but from the first, at the door, guests were greeted by a Swiss guard, splendidly bedecked and covered with gold from head to foot. The guard supposedly was responsible for bringing in the painters and poets who arrived, while barring the "infamous priests and the military." Eventually Salis' tongue-in-cheek admirational piece was on a high marble fireplace: The skull of Louis XIII as a child.[3]

Second site

Le Chat Noir soon outgrew its first site. Three and a half years after opening, its popularity forced it to move into larger accommodations a few doors down, in June 1885. Located at 12 Rue Victor-Masse (which before 1885 had been Rue de Laval 12), the new establishment was sumptuous. It was the old private mansion of the painter Alfred Stevens, who, at the request of Salis, had transformed it into a "fashionable country inn" with the help of the architect Maurice Isabey. On 10 June 1885, with great fanfare, Salis moved to new premises at 12 Rue Victor-Masse. Very quickly, poets and singers who performed at Le Chat Noir found the best practice for their craft to be had in Paris.

With exaggerated, ironic politeness, Salis most often played the role of conférencier (post-performance lecturer, or emcee). It was here that the Salon des Arts Incohérents (Salon of Incoherent Arts), shadow plays, and comic monologues got their start.

Salis declared that the Chat Noir is the most extraordinary cabaret in the world. You rub shoulders with the most famous men of Paris, meeting there with foreigners from every corner of the world."

Famous men and women to patronize the Chat Noir included Jane Avril, Franc-Nohain, Adolphe Willette, Caran d'Ache, André Gill, Émile Cohl, Paul Bilhaud, Sarah England, Paul Verlaine, Henri Rivière, Claude Debussy, Erik Satie, Charles Cros, Jules Laforgue, Yvette Guilbert, Charles Moréas, Albert Samain, Louis Le Cardonnel, Coquelin Cadet, Emile Goudeau, Alphonse Allais, Maurice Rollinat, Maurice Donnay, Armand Masson, Aristide Bruant, Théodore Botrel, Paul Signac, August Strindberg, George Auriol, Marie Krysinska, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Last location

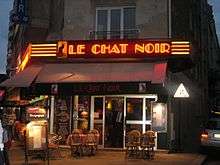

The cabaret would later move to 68, Boulevard de Clichy.

The last shadow play by Salis's company was staged in January 1897, after which Salis took the company on tour. Salis was talking of plans to move the cabaret to a location in Paris itself, but died on 19 March 1897. Other cabarets successfully copied and adapted the model established by the Chat Noir.[4] In December 1899 Henri Fursy opened his Boîte à Fursy cabaret in the former Chat Noir hôtel on rue Victor-Massé. He claimed to have inherited the mantle of Salis, and said his cabaret "has thanks to Fursy become once again the goal of all who 'climb Montmartre' to hear their favorite chansonniers..."[5]

Le Chat Noir on Boulevard de Clichy remained popular into the 1920s.[6] Today, this last location has been transformed into a modern boutique hotel, with a few nods to its raucous past.

Le Chat Noir

From 1892 to 1895 the cabaret published a weekly magazine with the same name, featuring literary writings, news from the cabaret and Montmartre, poetry, and political satire.[7]

Cultural associations

A poster of "Le Chat Noir" may be seen prominently in the crime scene photographs from the 2001 murder of Kathleen Peterson by her husband and novelist Michael Peterson.

Le Chat Noir is the name of the nightclub where Frank Sinatra and Natalie Wood rekindle their relationship, in the 1958 movie Kings Go Forth. There is also the famous cat painting with blinking eyes on the entrance wall.

References

- ↑ "Hommage à Salis le Grand", in 88 notes pour piano solo, Jean-Pierre Thiollet, Neva Editions, 2015, p. 146. ISBN 978 2 3505 5192 0

- ↑ Meakin, Anna. "Le Chat Noir: Historic Montmartre Cabaret". Bonjour Paris. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- ↑ Baldran 2002, p. 62.

- ↑ Whiting 1999, p. 52.

- ↑ Whiting 1999, p. 53.

- ↑ Nichols 2002, p. 119.

- ↑ Vogel 2009, p. 30.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Le Chat Noir. |

Sources

- Baldran, Jacqueline (2002). Paris, carrefour des arts et des lettres: 1880-1918. L'Harmattan. p. 62. ISBN 978-2-7475-3141-2. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- Nichols, Roger (2002). The Harlequin Years: Music in Paris, 1917-1929. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23736-0. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- Vogel, Shane (2009). The Scene of Harlem Cabaret: Race, Sexuality, Performance. U of Chicago P. p. 30. ISBN 9780226862521.

- Whiting, Steven Moore (1999-02-18). Satie the Bohemian : From Cabaret to Concert Hall: From Cabaret to Concert Hall. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-158452-7. Retrieved 2013-09-23.