Liberum veto

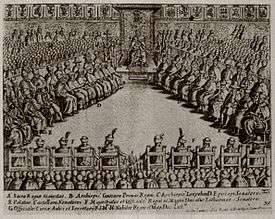

The liberum veto (Latin for "the free veto") was a parliamentary device in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was a form of unanimity voting rule that allowed any member of the Sejm (legislature) to force an immediate end to the current session and nullify any legislation that had already been passed at the session by shouting Sisto activitatem! (Latin: "I stop the activity!") or Nie pozwalam! (Polish: "I do not allow!"). The rule was in place from the mid-17th to the late 18th century in the Sejm's parliamentary deliberations. It was based on the premise that since all Polish noblemen were equal, every measure that came before the Sejm had to be passed unanimously. The principle of liberum veto was a key part of the political system of the Commonwealth, strengthening democratic elements and checking royal power, going against the European-wide trend of having a strong executive (absolute monarchy).

Many historians hold that the principle of liberum veto was a major cause of the deterioration of the Commonwealth political system—particularly in the 18th century, when foreign powers bribed Sejm members to paralyze its proceedings—and the Commonwealth's eventual destruction in the partitions of Poland and foreign occupation, dominance and manipulation of Poland for the next 200 years or so. Piotr Stefan Wandycz wrote that the "liberum veto had become the sinister symbol of old Polish anarchy." In the period of 1573–1763, about 150 sejms were held, out of which about a third failed to pass any legislation, mostly due to liberum veto. The expression Polish parliament in many European languages originated from this apparent paralysis.

History

Origin

This rule evolved from the principle of unanimous consent, which derived from the traditions of decision-making in the Kingdom of Poland, and developed under the federative character of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[1] Each deputy to a Sejm was elected at a sejmik (the local sejm for a region) and represented the entire region. He thus assumed responsibility to his sejmik for all decisions taken at the Sejm.[1] Since all noblemen were considered equal, a decision taken by a majority against the will of a minority (even if only a single sejmik) was considered a violation of the principle of political equality.[1]

At first, the dissenting deputies were often convinced or cowed back to withdraw their objections.[1] Also, in its early manifestation, the rule was used to strike down only individual laws, not to dissolve the chamber and throw out all measures passed.[2] For example, as historian Władysław Czapliński describes in the Sejm of 1611 context, some resolutions were struck down, but others passed.[2] From the mid-17th century onward, however, an objection to any item of Sejm legislation from a deputy or senator automatically caused other, earlier adopted legislation to be rejected. This was because all legislation adopted by a given Sejm formed a whole.[3]

It is commonly, and erroneously, believed that a Sejm was first disrupted by means of liberum veto by a Trakai deputy, Władysław Siciński, in 1652.[4] In reality, he only vetoed the continuation of the Sejm's deliberations beyond the statutory time limit.[3][5] He had, however, set up a dangerous precedent.[5][6] Over the proceedings of the next few sejms, the veto was still occasionally overruled, but the acceptance of it was gradually extended.[6] It was fewer than 20 years later, in 1669, in Kraków, that the entire Sejm was prematurely disrupted on the strength of the liberum veto before it had finished its deliberations.[3][5] This was done by the Kiev deputy, Adam Olizar.[7] The practice spiraled out of control, and in 1688 the Sejm was dissolved before the proceedings had begun or the Marshal of the Sejm was elected.[3][5]

Zenith

During the reign of John III Sobieski (1674–1696), half of Sejm proceedings were scuttled by the veto.[5] The practice also spread from the national Sejm to local sejmik proceedings.[5] In the first half of the 18th century, it became increasingly common for Sejm sessions to be broken up by liberum veto, as the Commonwealth's neighbours – chiefly Russia and Prussia — found this a useful tool to frustrate attempts at reforming and strengthening the Commonwealth. By bribing deputies to exercise their vetoes, Poland's neighbours could derail any measures not to their liking.[3] The Commonwealth deteriorated from a European power into a state of anarchy.[8] Only a few Sejms were able to meet during the reign of the House of Saxony in Poland (1696–1763), the last one in 1736.[3] Only eight out of 18 Sejm sessions during the reign of Augustus II (1697–1733) passed legislation.[9] For a period of 30 years around the reign of Augustus III, only one session was able to pass legislation (1734–1763).[10] The government was near collapse, giving rise to the term "Polish anarchy", and the country was managed by provincial assemblies and magnates.[10]

Disruption of the Commonwealth governance caused by the liberum veto was highly significant. In the period of 1573–1763, about 150 Sejms where held, of which 53 failed to pass any legislation.[3] Historian Jacek Jędruch notes that out of the 53 disrupted Sejms, 32 were disrupted due to liberum veto.[11]

Final years

The 18th century saw an institution known as a "confederated sejm" evolve.[12] It was a parliament session that operated under the rules of a confederation.[12] Its primary purpose was to avoid disruption by the liberum veto, unlike the national Sejm, which was paralyzed by the veto during this period.[12] On some occasions, a confederated sejm was formed of the whole membership of the national Sejm, so that the liberum veto would not operate there.[13]

The second half of the 18th century, marking the age of the Enlightenment in Poland, also witnessed an increased trend aiming at the reform of the inefficient governance of the Commonwealth.[14][15] Reforms of 1764–1766 improved the proceedings of the Sejm.[16] They introduced majority voting for non-crucial items, including most economic and tax matters, and outlawed binding instructions from sejmiks.[16] The road to reform was not easy, as conservatives, supported by foreign powers, opposed most of the changes, attempting to defend liberum veto and other elements perpetuating the inefficient governance, most notably through the Cardinal Laws of 1768.[17][18]

The liberum veto was finally abolished by the Constitution of 3 May 1791, adopted by a confederated sejm, which permanently established the principle of majority rule.[19] The achievements of that constitution, however – which historian Norman Davies called "the first constitution of its kind in Europe"[20] — were undone by another confederated sejm, meeting at Grodno in 1793. That Sejm, under duress from Russia and Prussia, ratified the Second Partition of Poland, anticipating the final disappearance of the Polish-Lithuanian state two years later.[21]

Significance

Harvard political scientist Grzegorz Ekiert, assessing the history of the liberum veto in the Kingdom of Poland, 1569-1795, concludes:

- The principle of the liberum veto preserved the feudal features of Poland's political system, weakened the role of the monarchy, led to anarchy in political life, and contributed to the economic and political decline of the Polish state. Such a situation made the country vulnerable to foreign invasions and ultimately led to its collapse.[22]

Political scientist Dalibor Roháč noted that the "principle of liberum veto played an important role in [the] emergence of the unique Polish form of constitutionalism" and acted as a significant constraint on the powers of the monarch by making the "rule of law, religious tolerance and limited constitutional government ... the norm in Poland in times when the rest of Europe was being devastated by religious hatred and despotism."[23] It was seen as one of the key principles of the Commonwealth political system and culture, the Golden Liberty.[24]

At the same time, historians hold that the principle of liberum veto was a major cause of the deterioration of the Commonwealth political system and Commonwealth's eventual downfall.[4] Deputies bribed by magnates or foreign powers, or simply content to believe they were living in some kind of "Golden Age", for over a century paralysed the Commonwealth's government, stemming any attempts at reform.[25][26] Piotr Stefan Wandycz wrote that the "liberum veto had become the sinister symbol of old Polish anarchy."[27] Wagner echoed him thus: "Certainly, there was no other institution of old Poland which has been more sharply criticized in more recent times than this one.".[28]

Modern parallels and popular culture

A 2004 Polish collectible card game, Veto, set in the background of a royal election during an election sejm, is named after this procedure.[29]

Until the early 1990s, IBM had a decision-making process called "non-concur" in which any department head could veto a company-wide strategy if it didn't fit in with his department's outlook. This effectively turned IBM into several independent fiefdoms. "Non-concur" was eliminated by CEO Louis Gerstner who was brought in to revive the declining company.[30]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.220-221

- 1 2 Władysław Czapliński, Władysław IV i jego czasy (Władysław IV and His Times). PW "Wiedza Poweszechna". Warszawa 1976, pp. 29

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.223

- 1 2 Jasienica, Paweł (1988). Polska anarchia (in Polish). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. ISBN 83-08-01970-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Francis Ludwig Carsten (1 January 1961). The new Cambridge modern history: The ascendancy of France, 1648–88. CUP Archive. pp. 561–562. ISBN 978-0-521-04544-5. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- 1 2 Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 117–119. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ Tadeusz Korzon (1898). Dola i Niedola Jana Sobieskiego, 1629–1674. Akademia Umiejetności. p. 262. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ↑ Barbara Markiewicz, "Liberum veto albo o granicach społeczeństwa obywatelskiego" [w:] Obywatel: odrodzenie pojęcia, Warszawa 1993.

- ↑ Piotr Stefan Wandycz (2001). The price of freedom: a history of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the present. Psychology Press. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-415-25491-5. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- 1 2 Norman Davies (20 January 1998). Europe: a history. HarperCollins. p. 659. ISBN 978-0-06-097468-8. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.225-226

- ↑ Jacek Jędruch (1998). Constitutions, elections, and legislatures of Poland, 1493–1977: a guide to their history. EJJ Books. pp. 136–138. ISBN 978-0-7818-0637-4. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.284-287

- ↑ Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.289

- 1 2 Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.293-294

- ↑ Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.297-298

- ↑ Norman Davies (30 March 2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 391. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ George Sanford (2002). Democratic government in Poland: constitutional politics since 1989. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-333-77475-5. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ↑ Davies, Norman (1996). Europe: A History. Oxford University Press. p. 699. ISBN 0-19-820171-0.

- ↑ Norman Davies (30 March 2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ Grzegorz Ekiert, “Veto, Liberum,” in Seymour Martin Lipset, ed. ‘’The Encyclopedia of Democracy’’ (1998) 4:1341

- ↑ Roháč, Dalibor (June 2008). "The unanimity rule and religious fractionalisation in the Polish-Lithuanian Republic" (PDF). Constitutional Political Economy. Springer. 19 (2): 111–128. doi:10.1007/s10602-008-9037-5. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ↑ Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodorski, and Michal Pietrzak, Historia panstwa i prawa polskiego (Warsaw: Paristwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1987, p.248-249

- ↑ William Bullitt; Francis P. Sempa (30 September 2005). The great globe itself: a preface to world affairs. Transaction Publishers. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-1-4128-0490-5. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ John Adams; George Wescott Carey (2000). The political writings of John Adams. Regnery Gateway. pp. 242–. ISBN 978-0-89526-292-9. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Piotr Stefan Wandycz (1980). The United States and Poland. Harvard University Press. pp. 87–. ISBN 978-0-674-92685-1. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Wagner, W.J. (1992). "May 3, 1791, and the Polish constitutional tradition". The Polish Review. 36 (4): 383–395. JSTOR 25778591.

- ↑ Veto! CCG | Board Game | BoardGameGeek

- ↑ Culture (1 December 2002). "An executive dressing down". London: Telegraph. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

Further reading

- Davies, Norman. God's Playground: The origins to 1795 (2005).

- Grzegorz Ekiert, “Veto, Liberum,” in Seymour Martin Lipset, ed. ‘’The Encyclopedia of Democracy’’ (1998) 4:1340-41

- Heinberg, John Gilbert. "History of the majority principle." The American Political Science Review (1926) 20#1 pp: 52-68. in JSTOR

- Lukowski, Jerzy. "Political Ideas among the Polish Nobility in the Eighteenth Century (to 1788)." The Slavonic and East European Review (2004): 1-26. in JSTOR

- Roháč, Dalibor. "The unanimity rule and religious fractionalisation in the Polish-Lithuanian Republic." Constitutional Political Economy (2008) 19#2 pp: 111-128.

- Roháč, Dalibor. "‘It Is by Unrule That Poland Stands’: Institutions and Political Thought in the Polish-Lithuanian Republic." The Independent Institute 13.2 (2008): 209-224. online