List of tallest mountains in the Solar System

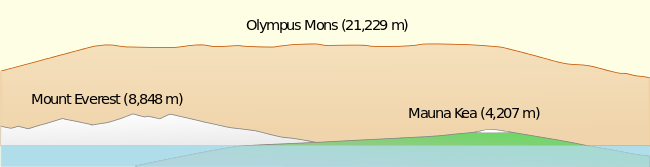

This is a list of the tallest mountains in the Solar System. The tallest peak or peaks on worlds where significant mountains have been measured are given; in some cases, the tallest peaks of different classes on a world are also listed. At 21.9 km, the enormous shield volcano Olympus Mons on Mars is the tallest mountain on any planet. For 40 years, following its discovery in 1971, it was the tallest mountain known in the Solar System. However, in 2011, the central peak of the crater Rheasilvia on the asteroid and protoplanet Vesta was found to be of comparable height.[lower-alpha 1]

List

The heights are given as base-to-peak, because there is no nonarbitrary equivalent to height above sea level on other worlds.

| World | Tallest peak(s) | Height | % of radius[lower-alpha 2] | Origin | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 Mercury | Caloris Montes | 030≤ 3 km (1.9 mi)[1][2] | 0123 0.12 | impact[3] | Formed by the Caloris impact |

| 02 Venus | Skadi Mons | 0646.4 km (4.0 mi) (approx.)[4] | 0106 0.11 | tectonic[5] | Has radar-bright slopes due to metallic Venus snow, possibly lead sulfide[6] |

| Maat Mons | 0494.9 km (3.0 mi) (approx.)[7] | 0081 0.081 | volcanic[8] | Highest volcano on Venus | |

| 03 Earth | Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa | 10210.2 km (6.3 mi)[9] | 0160 0.16 | volcanic | Just 4.2 km (2.6 mi) of this is above sea level |

| Pico del Teide | 0757.5 km (4.7 mi)[10] | 0118 0.12 | volcanic | Rises 3.7 km above sea level[10] | |

| Denali | 0565.3 to 5.9 km (3.3 to 3.7 mi)[11] | 0093 0.093 | tectonic | Tallest mountain base-to-peak on land[12][lower-alpha 3] | |

| Mount Everest | 0413.6 to 4.6 km (2.2 to 2.9 mi)[13] | 0072 0.072 | tectonic | 4.6 km on north face, 3.6 km on south face.[lower-alpha 4] | |

| 04 Moon | Mons Huygens | 0555.5 km (3.4 mi)[14][15] | 0317 0.32 | impact | Formed by the Imbrium impact |

| Mons Hadley | 0454.5 km (2.8 mi)[14][15] | 0259 0.26 | impact | Formed by the Imbrium impact | |

| Mons Rümker | 0111.1 km (0.68 mi)[16] | 0063 0.063 | volcanic | Largest volcanic construct on the Moon[16] | |

| 05 Mars | Olympus Mons | 219 21.9 km (14 mi)[17][18] | 0646 0.65 | volcanic | Rises 26 km above northern plains,[19] 1000 km away. Summit calderas are 60 x 80 km wide, up to 3.2 km deep;[18] scarp around margin is up to 8 km high.[20] |

| Ascraeus Mons | 14914.9 km (9.3 mi)[17] | 0440 0.44 | volcanic | Tallest of the three Tharsis Montes | |

| Elysium Mons | 12612.6 km (7.8 mi)[17] | 0372 0.37 | volcanic | Highest volcano in Elysium | |

| Arsia Mons | 117 11.7 km (7.3 mi)[17] | 0345 0.35 | volcanic | Summit caldera is 108 to 138 km (67 to 86 mi) across[17] | |

| Pavonis Mons | 084 8.4 km (5.2 mi)[17] | 0248 0.25 | volcanic | Summit caldera is 4.8 km (3.0 mi) deep[17] | |

| Anseris Mons | 062 6.2 km (3.9 mi)[21] | 0183 0.18 | impact | Among the highest nonvolcanic peaks on Mars, formed by the Hellas impact | |

| Aeolis Mons ("Mount Sharp") | 050 4.5 to 5.5 km (2.8 to 3.4 mi)[22][lower-alpha 5] | 0162 0.16 | depositional[lower-alpha 6] | Formed from deposits in Gale crater; MSL rover's long-term prime destination,[26] reached in November 2014.[27] | |

| 06 Vesta | Rheasilvia central peak | 22022 km (14 mi)[28][29] | 8370 8.4 | impact | Almost 200 km (120 mi) wide. See also: List of largest craters in the Solar System |

| 07 Ceres | Ahuna Mons | 0404 km (2.5 mi)[30] | 0853 0.85 | cryovolcanic[31] | Isolated steep-sided dome in relatively smooth area; max. height of ~ 5 km on steepest side; roughly antipodal to largest impact basin on Ceres |

| 08 Io | Boösaule Montes "South"[32] | 17817.5 to 18.2 km (10.9 to 11.3 mi)[33] | 0999 1.0 | tectonic | Has a 15 km (9 mi) high scarp on its SE margin[34] |

| Ionian Mons east ridge | 12712.7 km (7.9 mi) (approx.)[34][35] | 0697 0.70 | tectonic | Has the form of a curved double ridge | |

| Euboea Montes | 11810.3 to 13.4 km (6.4 to 8.3 mi)[36] | 0736 0.74 | tectonic | A NW flank landslide left a 25,000 km3 debris apron[37][lower-alpha 7] | |

| unnamed (245° W, 30° S) | 0202.5 km (1.6 mi) (approx.)[38][39] | 013 0.14 | volcanic | One of the tallest of Io's many volcanoes, with an atypical conical form[39][lower-alpha 8] | |

| 09 Mimas | Herschel central peak | 0707 km (4 mi) (approx.)[41] | 3530 3.5 | impact | See also: List of largest craters in the Solar System |

| 10 Dione | Janiculum Dorsa | 0151.5 km (0.9 mi)[42] | 0267 0.27 | tectonic[lower-alpha 9] | Surrounding crust depressed ca. 0.3 km. |

| 11 Titan | Mithrim Montes | 033373.3 km (2.1 mi)[44] | 013 0.13 | tectonic[44] | May have formed due to global contraction[45] |

| Doom Mons | 01451.45 km (0.90 mi)[46] | 0056 0.056 | cryovolcanic[46] | Adjacent to Sotra Patera, a 1.7 km (1.1 mi) deep collapse feature[46] | |

| 12 Iapetus | equatorial ridge | 20020 km (12 mi) (approx.)[47] | 2720 2.7 | uncertain[lower-alpha 10] | Individual peaks have not been measured |

| 13 Oberon | unnamed ("limb mountain") | 11011 km (7 mi) (approx.)[41] | 1440 1.4 | impact (?) | A value of 6 km was given shortly after the Voyager 2 encounter[51] |

| 14 Pluto | Piccard Mons[lower-alpha 11][52][53] | 056 ~5.6 km (3.5 mi)[54] | 0473 0.47 | cryovolcanic (?) | ~220 km across[54] |

| Wright Mons[lower-alpha 11][52][53] | 040 ~4.0 km (2.5 mi)[52] | 0330 0.34 | cryovolcanic (?) | ~160 km across;[52] summit depression ~56 km across[55] | |

| Norgay Montes[lower-alpha 11][56] | 035 ≤ 3.5 km (2.2 mi)[57] | 0295 0.30 | tectonic[57] (?) | Composed of water ice;[57] named after Tenzing Norgay[58] |

Gallery

The following images are shown in order of decreasing base-to-peak height.

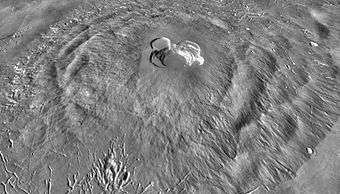

Olympus Mons on Mars as viewed from Viking 1 in 1978

Olympus Mons on Mars as viewed from Viking 1 in 1978 Cassini image of Iapetus's equatorial ridge

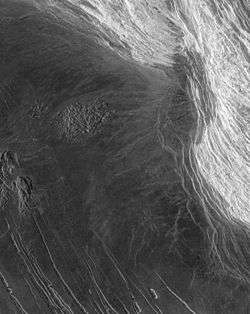

Cassini image of Iapetus's equatorial ridge Voyager 1 photo of Io's highest peak, Boösaule Montes "South"

Voyager 1 photo of Io's highest peak, Boösaule Montes "South"

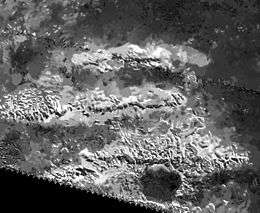

Io's Euboea Montes (below top left), Haemus Montes (lower right); north is left

Io's Euboea Montes (below top left), Haemus Montes (lower right); north is left

Cassini photo of Herschel crater on Mimas and its central peak

Cassini photo of Herschel crater on Mimas and its central peak

Aeolis Mons ("Mount Sharp"), Mars (as viewed by the rover Curiosity on 6 August, 2012).[lower-alpha 12]

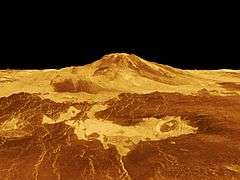

Aeolis Mons ("Mount Sharp"), Mars (as viewed by the rover Curiosity on 6 August, 2012).[lower-alpha 12] Maat Mons, Venus (radar imaging plus altimetry, 10x vertical exaggeration)

Maat Mons, Venus (radar imaging plus altimetry, 10x vertical exaggeration) The Moon's Mons Hadley, near the Apollo 15 landing site (1971)

The Moon's Mons Hadley, near the Apollo 15 landing site (1971)

New Horizons image of the enigmatic Norgay Montes of Pluto

New Horizons image of the enigmatic Norgay Montes of Pluto

Radar-generated view of Titan's cryovolcanic Doom Mons and Sotra Patera (10x vertical stretch)

Radar-generated view of Titan's cryovolcanic Doom Mons and Sotra Patera (10x vertical stretch)

See also

- List of extraterrestrial volcanoes

- List of largest craters in the Solar System

- List of largest rifts and valleys in the Solar System

- List of largest lakes and seas in the Solar System

- Mons (astrogeology)

- Topographic prominence

- List of the highest mountains on Earth

Notes

- ↑ Olympus Mons, however, is a much broader peak; its diameter is similar to that of Vesta itself.

- ↑ 100 x ratio of peak height to radius of the parent world

- ↑ On p. 20 of Helman (2005): "the base to peak rise of Mount McKinley is the largest of any mountain that lies entirely above sea level, some 18,000 ft (5,500 m)"

- ↑ Peak is 8.8 km (5.5 mi) above sea level, and over 13 km (8.1 mi) above the oceanic abyssal plain.

- ↑ About 5.25 km (3.26 mi) high from the perspective of the landing site of Curiosity.[23]

- ↑ A crater central peak may sit below the mound of sediment. If that sediment was deposited while the crater was flooded, the crater may have once been entirely filled before erosional processes gained the upper hand.[22] However, if the deposition was due to katabatic winds, as suggested by reported 3 degree radial slopes of the mound's layers, the role of erosion would have been to place an upper limit on the mound's growth.[24][25]

- ↑ Among the Solar System's largest[37]

- ↑ Some of Io's paterae are surrounded by radial patterns of lava flows, indicating they are on a topographic high point, making them shield volcanoes. Most of these volcanoes exhibit relief of less than 1 km. A few have more relief; Ruwa Patera rises 2.5 to 3 km over its 300 km width. However, its slopes are only on the order of a degree.[40] A handful of Io's smaller shield volcanoes have steeper, conical profiles; the example listed is 60 km across and has slopes averaging 4° and reaching 6-7° approaching the small summit depression.[40]

- ↑ Was apparently formed via contraction.[43]

- ↑ Hypotheses of origin include crustal readjustment associated with a decrease in oblateness due to tidal locking,[48][49] and deposition of deorbiting material from a former ring around the moon.[50]

- 1 2 3 Name not yet approved by the IAU

- ↑ A linearized wide-angle hazcam image that makes the mountain look steeper than it actually is. The highest peak is not visible in this view.

References

- ↑ "Surface". MESSENGER web site. Johns Hopkins University/Applied Physics Lab. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ Oberst, J.; Preusker, F.; Phillips, R. J.; Watters, T. R.; Head, J. W.; Zuber, M. T.; Solomon, S. C. (2010). "The morphology of Mercury's Caloris basin as seen in MESSENGER stereo topographic models". Icarus. 209 (1): 230–238. Bibcode:2010Icar..209..230O. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.03.009. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ↑ Fassett, C. I.; Head, J. W.; Blewett, D. T.; Chapman, C. R.; Dickson, J. L.; Murchie, S. L.; Solomon, S. C.; Watters, T. R. (2009). "Caloris impact basin: Exterior geomorphology, stratigraphy, morphometry, radial sculpture, and smooth plains deposits". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 285 (3-4): 297–308. Bibcode:2009E&PSL.285..297F. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.05.022. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ↑ Jones, Tom; Stofan, Ellen (2008). Planetology : Unlocking the secrets of the solar system. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-4262-0121-9.

- ↑ Keep, M.; Hansen, V. L. (1994). "Structural history of Maxwell Montes, Venus: Implications for Venusian mountain belt formation". Journal of Geophysical Research. 99 (E12): 26015. Bibcode:1994JGR....9926015K. doi:10.1029/94JE02636. ISSN 0148-0227.

- ↑ Otten, Carolyn Jones (10 February 2004). "'Heavy metal' snow on Venus is lead sulfide". Newsroom. Washington University in Saint Louis. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ "PIA00106: Venus - 3D Perspective View of Maat Mons". Planetary Photojournal. Jet Propulsion Lab. 1996-08-01. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ Robinson, C. A.; Thornhill, G. D.; Parfitt, E. A. (January 1995). "Large-scale volcanic activity at Maat Mons: Can this explain fluctuations in atmospheric chemistry observed by Pioneer Venus?". Journal of Geophysical Research. 100 (E6): 11755–11764. Bibcode:1995JGR...10011755R. doi:10.1029/95JE00147. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ "Mountains: Highest Points on Earth". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- 1 2 "Teide National Park". UNESCO World Heritage Site list. UNESCO. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ "NOVA Online: Surviving Denali, The Mission". NOVA web site. Public Broadcasting Corporation. 2000. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- ↑ Adam Helman (2005). The Finest Peaks: Prominence and Other Mountain Measures. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-5995-4. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ↑ Mount Everest (1:50,000 scale map), prepared under the direction of Bradford Washburn for the Boston Museum of Science, the Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research, and the National Geographic Society, 1991, ISBN 3-85515-105-9

- 1 2 Fred W. Price (1988). The Moon observer's handbook. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33500-0.

- 1 2 Moore, Patrick (2001). On the Moon. London: Cassell & Co.

- 1 2 Wöhler, C.; Lena, R.; Pau, K. C. (16 March 2007), The Lunar Dome Complex Mons Rümker: Morphometry, Rheology, and Mode of Emplacement, League City, Texas: Dordrecht, D. Reidel Publishing Co, retrieved 28 August 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Plescia, J. B. (2004). "Morphometric properties of Martian volcanoes". Journal of Geophysical Research. 109 (E3). Bibcode:2004JGRE..109.3003P. doi:10.1029/2002JE002031. ISSN 0148-0227.

- 1 2 Carr, Michael H. (11 January 2007). The Surface of Mars. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-139-46124-5.

- ↑ Comins, Neil F. (4 January 2012). Discovering the Essential Universe. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4292-5519-6. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ↑ Lopes, R.; Guest, J. E.; Hiller, K.; Neukum, G. (January 1982). "Further evidence for a mass movement origin of the Olympus Mons aureole". Journal of Geophysical Research. 87 (B12): 9917–9928. doi:10.1029/JB087iB12p09917.

- ↑ JMARS MOLA elevation dataset. Christensen, P.; Gorelick, N.; Anwar, S.; Dickenshied, S.; Edwards, C.; Engle, E. (2007) "New Insights About Mars From the Creation and Analysis of Mars Global Datasets;" American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting, abstract #P11E-01.

- 1 2 "Gale Crater's History Book". Mars Odyssey THEMIS web site. Arizona State University. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ↑ Anderson, R. B.; Bell III, J. F. (2010). "Geologic mapping and characterization of Gale Crater and implications for its potential as a Mars Science Laboratory landing site". International Journal of Mars Science and Exploration. 5: 76–128. Bibcode:2010IJMSE...5...76A. doi:10.1555/mars.2010.0004.

- ↑ Wall, M. (6 May 2013). "Bizarre Mars Mountain Possibly Built by Wind, Not Water". Space.com. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ↑ Kite, E. S.; Lewis, K. W.; Lamb, M. P.; Newman, C. E.; Richardson, M. I. (2013). "Growth and form of the mound in Gale Crater, Mars: Slope wind enhanced erosion and transport". Geology. 41 (5): 543–546. doi:10.1130/G33909.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ↑ Agle, D. C. (28 March 2012). "'Mount Sharp' On Mars Links Geology's Past and Future". NASA. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ Webster, Gay; Brown, Dwayne (9 November 2014). "Curiosity Arrives at Mount Sharp". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ Vega, P. (11 October 2011). "New View of Vesta Mountain From NASA's Dawn Mission". Jet Propulsion Lab's Dawn mission web site. NASA. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ↑ Schenk, P.; Marchi, S.; O'Brien, D. P.; Buczkowski, D.; Jaumann, R.; Yingst, A.; McCord, T.; Gaskell, R.; Roatsch, T.; Keller, H. E.; Raymond, C.A.; Russell, C. T. (1 March 2012), Mega-Impacts into Planetary Bodies: Global Effects of the Giant Rheasilvia Impact Basin on Vesta, The Woodlands, Texas: LPI, contribution 1659, id.2757, retrieved 6 September 2012

- ↑ "Dawn's First Year at Ceres: A Mountain Emerges". JPL Dawn website. Jet Propulsion Lab. 2016-03-07. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- ↑ Ruesch, O.; Platz, T.; Schenk, P.; McFadden, L. A.; Castillo-Rogez, J. C.; Quick, L. C.; Byrne, S.; Preusker, F.; OBrien, D. P.; Schmedemann, N.; Williams, D. A.; Li, J.- Y.; Bland, M. T.; Hiesinger, H.; Kneissl, T.; Neesemann, A.; Schaefer, M.; Pasckert, J. H.; Schmidt, B. E.; Buczkowski, D. L.; Sykes, M. V.; Nathues, A.; Roatsch, T.; Hoffmann, M.; Raymond, C. A.; Russell, C. T. (2016-09-02). "Cryovolcanism on Ceres". Science. 353 (6303): aaf4286–aaf4286. doi:10.1126/science.aaf4286.

- ↑ Perry, Jason (27 January 2009). "Boösaule Montes". Gish Bar Times blog. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ Schenk, P.; Hargitai, H. "Boösaule Montes". Io Mountain Database. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- 1 2 Schenk, P.; Hargitai, H.; Wilson, R.; McEwen, A.; Thomas, P. (2001). "The mountains of Io: Global and geological perspectives from Voyager and Galileo". Journal of Geophysical Research. 106 (E12): 33201. Bibcode:2001JGR...10633201S. doi:10.1029/2000JE001408. ISSN 0148-0227.

- ↑ Schenk, P.; Hargitai, H. "Ionian Mons". Io Mountain Database. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ Schenk, P.; Hargitai, H. "Euboea Montes". Io Mountain Database. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- 1 2 Martel, L. M. V. (16 February 2011). "Big Mountain, Big Landslide on Jupiter's Moon, Io". NASA Solar System Exploration web site. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ Moore, J. M.; McEwen, A. S.; Albin, E. F.; Greeley, R. (1986). "Topographic evidence for shield volcanism on Io". Icarus. 67 (1): 181–183. Bibcode:1986Icar...67..181M. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(86)90183-1. ISSN 0019-1035.

- 1 2 Schenk, P.; Hargitai, H. "Unnamed volcanic mountain". Io Mountain Database. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- 1 2 Schenk, P. M.; Wilson, R. R.; Davies, R. G. (2004). "Shield volcano topography and the rheology of lava flows on Io". Icarus. 169 (1): 98–110. Bibcode:2004Icar..169...98S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.01.015.

- 1 2 Moore, Jeffrey M.; Schenk, Paul M.; Bruesch, Lindsey S.; Asphaug, Erik; McKinnon, William B. (October 2004). "Large impact features on middle-sized icy satellites" (PDF). Icarus. 171 (2): 421–443. Bibcode:2004Icar..171..421M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.05.009.

- ↑ Hammond, N. P.; Phillips, C. B.; Nimmo, F.; Kattenhorn, S. A. (March 2013). "Flexure on Dione: Investigating subsurface structure and thermal history". Icarus. 223 (1): 418–422. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2012.12.021.

- ↑ Beddingfield, C. B.; Emery, J. P.; Burr, D. M. (March 2013), Testing for a Contractional Origin of Janiculum Dorsa on the Northern, Leading Hemisphere of Saturn's Moon Dione, The Woodlands, Texas: Lunar and Planetary Institute, p. 1301, retrieved 23 December 2014

- 1 2 "PIA20023: Radar View of Titan's Tallest Mountains". Photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2016-03-24. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- ↑ Mitri, G.; Bland,M. T.; Showman, A. P.; Radebaugh, J.; Stiles, B.; Lopes, R. M. C.; Lunine, J. I.; Pappalardo, R. T. (2010). "Mountains on Titan: Modeling and observations". Journal of Geophysical Research. 115 (E10002): 1–15. Bibcode:2010JGRE..11510002M. doi:10.1029/2010JE003592. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 Lopes, R. M. C.; Kirk, R. L.; Mitchell, K. L.; LeGall, A.; Barnes, J. W.; Hayes, A.; Kargel, J.; Wye, L.; Radebaugh, J.; Stofan, E. R.; Janssen, M. A.; Neish, C. D.; Wall, S. D.; Wood, C. A.; Lunine, J. I.; Malaska, M. J. (19 March 2013). "Cryovolcanism on Titan: New results from Cassini RADAR and VIMS". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 118: 1–20. Bibcode:2013JGRE..118..416L. doi:10.1002/jgre.20062. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- ↑ Giese, B.; Denk, T.; Neukum, G.; Roatsch, T.; Helfenstein, P.; Thomas, P. C.; Turtle, E. P.; McEwen, A.; Porco, C. C. (2008). "The topography of Iapetus' leading side" (PDF). Icarus. 193 (2): 359–371. Bibcode:2008Icar..193..359G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.06.005. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ↑ Porco, C. C.; et al. (2005). "Cassini Imaging Science: Initial Results on Phoebe and Iapetus". Science. 307 (5713): 1237–1242. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1237P. doi:10.1126/science.1107981. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15731440. 2005Sci...307.1237P.

- ↑ Kerr, Richard A. (2006-01-06). "How Saturn's Icy Moons Get a (Geologic) Life". Science. 311 (5757): 29. doi:10.1126/science.311.5757.29. PMID 16400121.

- ↑ Ip, W.-H. (2006). "On a ring origin of the equatorial ridge of Iapetus" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 33 (16): L16203. Bibcode:2006GeoRL..3316203I. doi:10.1029/2005GL025386. ISSN 0094-8276.

- ↑ Moore, P.; Henbest, N. (April 1986). "Uranus - the View from Voyager". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 96 (3): 131–137. Bibcode:1986JBAA...96..131M. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "At Pluto, New Horizons Finds Geology of All Ages, Possible Ice Volcanoes, Insight into Planetary Origins". New Horizons News Center. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory LLC. 2015-11-09. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- 1 2 Witze, A. (2015-11-09). "Icy volcanoes may dot Pluto's surface". Nature News and Comment. Nature Publishing Group. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- 1 2 "Ice Volcanoes and Topography". New Horizons Multimedia. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory LLC. 2015-11-09. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- ↑ "Ice Volcanoes on Pluto?". New Horizons Multimedia. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory LLC. 2015-11-09. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- ↑ Hand, E.; Kerr, R. (17 July 2015). "Potential geysers spotted on Pluto". Science. 349. doi:10.1126/science.aac8875.

- 1 2 3 Hand, E.; Kerr, R. (15 July 2015). "Pluto is alive—but where is the heat coming from?". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aac8860.

- ↑ Pokhrel, Rajan (19 July 2015). "Nepal's mountaineering fraternity happy over Pluto mountains named after Tenzing Norgay Sherpa - Nepal's First Landmark In The Solar System". The Himalayan Times. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to List of tallest mountains in the Solar System. |

- 3-D anaglyphs of Rheasilvia's central peak at photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov: top view and side view

- Color views of Rheasilvia's central peak at Planetary.org: side view (peak is at upper right) and mosaic of Vesta's southern hemisphere

- Color panorama of Aeolis Mons from 21 September 2012

- Gigapixel panorama of the Mt. Everest area by David Breashears