London After Midnight (film)

| London After Midnight | |

|---|---|

|

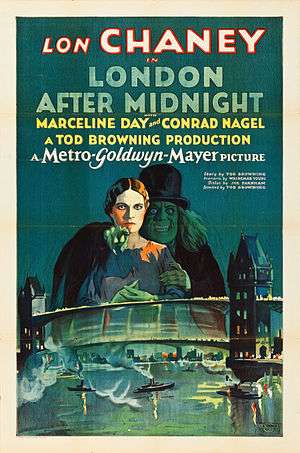

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tod Browning |

| Produced by |

Tod Browning Irving Thalberg (uncredited) |

| Written by |

Waldemar Young (scenario) Joseph W. Farnham (titles) |

| Based on |

"The Hypnotist" by Tod Browning |

| Starring |

Lon Chaney Marceline Day Conrad Nagel Henry B. Walthall Polly Moran Claude King |

| Cinematography | Merritt B. Gerstad |

| Edited by |

Harry Reynolds Irving Thalberg (uncredited) |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 65 mins[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language |

Silent English intertitles |

London After Midnight (also known as The Hypnotist) was a 1927 American silent mystery film with horror overtones distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The film was based on the short story "The Hypnotist" by Tod Browning who also directed the film. London After Midnight starred Lon Chaney, Marceline Day, Conrad Nagel, Henry B. Walthall, and Polly Moran.

The movie is now lost and remains one of the most famous and eagerly sought of all lost films. The last known copy was destroyed in the 1967 MGM Vault fire.[2] In 2002, Turner Classic Movies aired a reconstructed version, using the original script and film stills, by producer Rick Schmidlin.[3]

Plot

A cultured and peaceful home on the outskirts of London.[4] The head of the house, Roger Balfour, is found dead of a bullet wound and he appears to have been killed by his own hand.[4][5][6]

Some five years later, Edward C. Burke of Scotland Yard, detective and hypnotist must reproduce the scene of the crime and hypnotize the suspect into re-enacting the murder.[5][6][7]

The characters consist of Sir James Hamlin, Roger Balfour's friend and neighbor,[7] Arthur Hibbs, Sir James Hamlin's nephew, and Williams, the butler of the Balfours.[7] The daughter of Roger Balfour, Lucille Balfour, is the only person beyond suspicion.[7]

Cast

- Lon Chaney - Professor/(or Inspector) Edward C. Burke/The Man in the Beaver Hat

- Marceline Day - Lucille Balfour[6]

- Henry B. Walthall - Sir James Hamlin[6]

- Percy Williams - Williams, Balfour's Butler[6]

- Conrad Nagel - Arthur Hibbs[6]

- Polly Moran - Miss Smithson, the New Maid[6]

- Edna Tichenor - Luna, a Bat Girl[6]

- Claude King - Roger Balfour / The Stranger[6]

Production notes

Chaney's makeup for the film included sharpened teeth and the hypnotic eye effect he achieved with special wire fittings which he wore like monocles. Based on surviving accounts, he purposefully gave the "vampire" character an absurd quality, because it was the film's Scotland Yard detective character (also played by Chaney) in a disguise. Surviving stills show this was the only time Chaney used his famous makeup case as an on-screen prop.

The story was an original work by Tod Browning and Waldemar Young was the scenario writer who had previously worked with Browning on The Unholy Three and The Unknown. Young was previously employed as a journalist in San Francisco which included covering several famous murders, a distinction which was lauded as knowing "mystery from actual experience."[8]

In the film, Chaney in the role of Burke uses different disguises, but the film "even lets the audience into the secrets of his makeup, when as the detective, he applies a disguise before the eyes of the audience."[9]

When London After Midnight premiered at the Miller Theater in Missouri, set musicians Sam Feinburg and Jack Feinburg had to prepare melodies to go with the film's supernatural elements. The musicians used Ase's Todd and Eritoken by Greig, Dramatic Andante by Rappe, the Fire Music from Wagner's The Valkyrie and other unlisted aspects of Savino, Zimonek and Puccini.[10]

Reception

The film grossed $721,000 at the box office domestically against a production budget of $152,000,[11] becoming the most successful collaborative film between Chaney and Browning. However, contemporary accounts by filmgoers and critics suggest it was not one of Chaney and Browning's strongest films. The storyline, called "somewhat incoherent" by the New York Times[11] and "nonsensical" by Harrison's Reports,[12] was a common point of criticism.

A positive review ran in Film Daily, calling it "a story certain to disturb the nervous system of the more sensitive picture patrons. If they don't get the creeps from flashes of grimy bats swooping around, cobweb-bedecked mystery chambers and the grotesque inhabitants of the haunted house, then they've passed the third degree."[12]

The Warren Tribune noted that Lon Chaney is "present in nearly every scene, in a dual role that tests his skill to no small degree."[13] The review highlighted that this subdues Chaney's prominence and allows the plot to be better communicated, but it also causes the film to "not rank among his best productions."[13]

A review by The Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted, "[i]t is pleasant to report also that there is none of the usual stupid comedy relief in London After Midnight to mar its sinister and creepy scheme."[6] It however found fault in Tod Browning's direction because the film's atmosphere did not recapture "the intensely weird effect" found in The Cat and the Canary.[6]

Variety wrote that "Young, Browning and Chaney have made a good combination in the past but the story on which this production is based is not of the quality that results in broken house records," and that since Burke was "a detached character, mechanical and wooden", he failed to meaningfully connect with the audience.[14]

The New Yorker also panned the film, writing that the "directing, acting and settings are all well up to the idea," but "it strives too hard to create effect. Mr. Browning can create pictorial terrors and Lon Chaney can get himself up in a completely repulsive manner, but both their efforts are wasted when the story makes no sense."[15]

Film historian William K. Everson, who viewed the film in the early 1950s, called it "routine"[12] and inferior to the 1935 remake Mark of the Vampire.[11]

Reconstruction

In 2002, Turner Classic Movies commissioned restoration producer Rick Schmidlin to produce a 45-minute reconstruction of the film, using still photographs.[3] The following year, the reconstructed version was released as a part of The Lon Chaney Collection DVD set released by the TCM Archives.[16]

Remake

Tod Browning remade the film as a talkie called Mark of the Vampire in 1935 with Lionel Barrymore and Bela Lugosi playing Chaney's roles.

In popular culture

A novelization of the film was written and published in 1928 by Marie Coolidge-Rask.[1]

The film was used as a part of the defense for a man accused of murdering a woman in Hyde Park, London in 1928. He claimed Chaney's performance drove him temporarily insane, but his plea was rejected and he was convicted of the crime. Electric Sheep Magazine republished The Times account which stated, "[the prisoner] thought he saw Lon Chaney, a film actor, in a corner, shouting and making faces at him. He did not remember taking a razor from his pocket, or using the razor on the girl or on himself."[1]

This film also played a big part in the final third-season episode of the TV series Whitechapel where a psychopath is driven insane by watching a previously-unknown last copy of London After Midnight. After watching it for one last time, he hands it over to one of the police and asks him to protect it.

There is an industrial-goth-rock band called London After Midnight.

The song "Bodom after midnight", from the metal band Children of Bodom references the movie.

The Man in the Beaver Hat was used as the design basis for the Hatbox Ghost during his short run in Disneyland's Haunted Mansion attraction.

The Man in the Beaver Hat was also an inspiration for the design of the Babadook in the 2014 psychological horror film The Babadook. [17]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Giles, Jane (8 November 2013). "London after Midnight The literary history of Hollywood's first vampire movie". Electric Sheep Magazine. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ London After Midnight American Silent Feature Film Survival Database

- 1 2 Vogel, Michelle (2010). Olive Borden: The Life and Films of Hollywood's "Joy Girl". McFarland. p. 146. ISBN 0-786-44795-8.

- 1 2 ""London After Midnight" Opens at Library Today". The Warren Tribune (Warren, Pennsylvania). 30 January 1928. p. 3. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- 1 2 "Now Showing". Corsicana Daily Sun (Corsicana, Texas). 12 December 1927. p. 5. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "At the Capitol". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York). 12 December 1927. p. 30. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "London After Midnight - Circle". The Indianapolis News (Indianapolis, Indiana). 9 January 1928. p. 7. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ "Lon Chaney Star in London After Midnight Palace". Corsicana Daily Sun (Corsicana, Texas). 12 December 1927. p. 5. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ "Lon Chaney in Mystery Film at Loew's Colonial". Reading Times (Reading, Pennsylvania). 5 January 1928. p. 8. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ "Lon Chaney Comes to Miller on Wednesday". The Daily Capital News (Jefferson City, Missouri). 1 January 1928. p. 3. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 Mirsalis, Jon C. "London After Midnight". lonchaney.org. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Soister, John; Nicolella, Henry (2012). American Silent Horror, Science Fiction and Fantasy Feature Films, 1913-1929. McFarland & Company. pp. 335–336.

- 1 2 "After Six in Warren". The Warren Tribune (Warren, Pennsylvania). 31 January 1928. p. 3. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ "Film Reviews". Variety. New York: Variety, Inc.: 18 December 14, 1927.

- ↑ Claxton, Oliver (December 17, 1927). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. New York: F-R Publishing Company: 103.

- ↑ Cline, John; Weiner. Robert G., eds. (2010). From the Arthouse to the Grindhouse: Highbrow and Lowbrow Transgression in Cinema's First Century. Scarecrow Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-810-87655-8.

- ↑ https://mountainx.com/movies/interview-with-the-babadooks-writer-director-jennifer-kent/

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: London After Midnight (film) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to London After Midnight. |

- London After Midnight at the Internet Movie Database

- London After Midnight at AllMovie

- London After Midnight at the TCM Movie Database

- Spanish-language poster for London After Midnight