Amblyomma americanum

| Lone star tick | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Subclass: | Acari |

| Order: | Ixodida |

| Family: | Ixodidae |

| Genus: | Amblyomma |

| Species: | A. americanum |

| Binomial name | |

| Amblyomma americanum (Linnaeus, 1758) [1] | |

| |

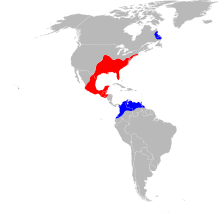

| Red indicates where the species is normally found; Blue indicates other locations where the species has been reported | |

Amblyomma americanum, or lone star tick, is a species of tick in the genus Amblyomma.

Distribution

It is very widespread in the United States ranging from Texas to central Wisconsin in the Midwest and east to the coast where it can be found as far north as Maine,[2] as far south as Guatemala, and sightings of this species have been reported in Québec, Colombia and Ecuador. It is most common in wooded areas, particularly in forests with thick underbrush, and large trees.

Development

The tick follows the normal development stages of egg, larva, nymph and adult. It is known as a 3-host tick, meaning that it feeds from a different host during the larval, nymphal, and adult stages. The lone star tick attaches itself to a host by way of questing.[3]

Vector

Like all ticks, it can be a vector of diseases including human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia chaffeensis), canine and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia ewingii), tularemia (Francisella tularensis), and southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI, possibly caused by the spirochete Borrelia lonestari).[4] STARI exhibits a rash similar to that caused by Lyme disease, but is generally considered to be less severe.

Though the primary bacterium responsible for Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, has occasionally been isolated from lone star ticks, numerous vector competency tests have demonstrated that this tick is extremely unlikely to be capable of transmitting Lyme disease. Some evidence indicates A. americanum saliva inactivates B. burgdorferi more quickly than the saliva of Ixodes scapularis.[5] Recently the bacteria Borrelia andersonii and Borrelia americana have been linked to Amblyomma americanum.[6]

In response to two cases of severe febrile illness occurring in two farmers in northwestern Missouri, researchers determined the lone star tick can transmit the heartland virus in 2013.[7] Six more cases were identified in 2012–2013 in Missouri and Tennessee.[8]

Meat allergy

The bite of this tick can cause a person to develop a meat allergy to nonprimate mammalian meat and meat products.[9] This allergy is characterized by adult onset, and a delayed reaction of urticaria or anaphylaxis appearing 4–8 hours after consumption of the allergen. The allergen has been identified as a carbohydrate called galactose-α-1,3-galactose (alpha gal). As well as occurring in nonprimate mammals, alpha gal is also found in cat dander and a drug used to treat head and neck cancer. Commercial tests for alpha gal IgE became available following research.

See also

Bibliography

- Piesman J, Sinsky RJ., Ability of Ixodes scapularis, Dermacentor variabilis, and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) to acquire, maintain, and transmit Lyme disease spirochetes (Borrelia burgdorferi) ; J Med Entomol. 1988 September; 25(5):336-9.

References

- ↑ Amblyomma americanum at the Encyclopedia of Life

- ↑ James E. Childs; Christopher D. Paddock (2003). "The ascendancy of Amblyomma americanum as a vector of pathogens affecting humans in the United States". Annual Review of Entomology. 48 (1): 307–337. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112728. PMID 12414740.

- ↑ Holderman, Christopher J., and Phillip E. Kaufman. Lone Star Tick Amblyomma Americanum (Linnaeus): (Acari: Ixodidae). Entomology and Nematology Department, UF/IFAS Extension. The Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS), Jan. 2014. Web.

- ↑ Edwin J. Masters; Chelsea N. Grigery; Reid W. Masters (June 2008). "STARI, or Masters disease: lone star tick-vectored Lyme-like illness". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 22 (2): 361–376, viii. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2007.12.010. PMID 18452807.

- ↑ K. E. Ledin; N. S. Zeidner; J. M. C. Ribeiro; B. J. Biggerstaff; M. C. Dolan; G. Dietrich; L. VredEvoe; J. Piesman (March 2005). "Borreliacidal activity of saliva of the tick Amblyomma americanum". Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 19 (1): 90–95. doi:10.1111/j.0269-283X.2005.00546.x. PMID 15752182.

- ↑ Kerry L. Clark; Brian Leydet; Shirley Hartman (2013). "Lyme Borreliosis in Human Patients in Florida and Georgia, USA". Int J Med Sci. 10 (7): 915–931. doi:10.7150/ijms.6273. ISSN 1449-1907.

- ↑ Harry M. Savage; Marvin S. Godsey Jr.; Amy Lambert; Nickolas A. Panella; Kristen L. Burkhalter; Jessica R. Harmon; R. Ryan Lash; David C. Ashley; William L. Nicholson (22 July 2013). "First Detection of Heartland Virus (Bunyaviridae: Phlebovirus) from Field Collected Arthropods". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 89 (3): 445–452. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.13-0209. PMC 3771279

. PMID 23878186.

. PMID 23878186. - ↑ "CDC Reports More Cases of Heartland Virus Disease". CDC. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ↑ Commins, Scott P.; James, Hayley R.; Kelly, Libby A.; Pochan, Shawna L.; Workman, Lisa J.; Perzanowski, Matthew S.; Kocan, Katherine M.; Fahy, John V.; Nganga, Lucy W.; Ronmark, Eva; Cooper, Philip J.; Platts-Mills, Thomas A.E. (May 2011). "The relevance of tick bites to the production of IgE antibodies to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-α-1,3-galactose". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 127 (5): 1286–1293. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.019. PMC 3085643

. PMID 21453959. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

. PMID 21453959. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

External links

Data related to Amblyomma americanum at Wikispecies

Data related to Amblyomma americanum at Wikispecies Media related to Amblyomma americanum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Amblyomma americanum at Wikimedia Commons- http://www.k-state.edu/parasitology/625tutorials/Tick03.html