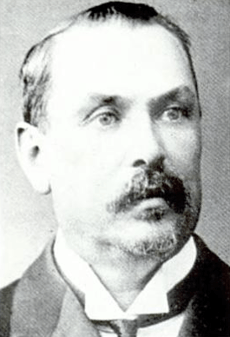

Louis Botha

| The Right Honourable Louis Botha | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of South Africa | |

|

In office 31 May 1910 – 27 August 1919 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Governor-General |

The Viscount Gladstone The Earl Buxton |

| Preceded by | Office Established |

| Succeeded by | Jan Christiaan Smuts |

| Prime Minister of the Transvaal | |

|

In office 4 February 1907[1] – 31 May 1910 | |

| Monarch |

Edward VII George V |

| Governor | The Earl of Selborne |

| Preceded by | Office Established |

| Succeeded by |

Himself As Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

27 September 1862 Greytown, Colony of Natal |

| Died |

27 August 1919 (aged 56) Pretoria, Transvaal Province, Union of South Africa |

| Resting place | Heroes' Acre, Pretoria, South Africa |

| Nationality | Boer, Afrikaner |

| Political party | South African Party |

| Other political affiliations | Het Volk Party |

| Spouse(s) | Annie Emmett |

| Profession | Career military officer, politician |

| Religion | Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Years of service | 1899–1902 (Transvaal commandos) |

| Rank | General |

| Commands | Boer, South African Republic |

| Battles/wars |

Second Boer War: -- Colenso -- Spioen kop -- Retreat from Pretoria First World War: -- South-West Africa Campaign |

Louis Botha (27 September 1862 – 27 August 1919) was a South African politician who was the first Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa—the forerunner of the modern South African state. A Boer war hero during the Second Boer War, he would eventually fight to have South Africa become a British Dominion.

Biography

He was born in Greytown, Natal as one of 13 children born to Louis Botha Senior (26 March 1827 – 5 July 1883) and Salomina Adriana van Rooyen (31 March 1829 – 9 January 1886). He briefly attended the school at Hermannsburg before his family relocated to the Orange Free State. The name Louis runs throughout the family, with every generation since General Louis Botha having the eldest son named Louis.

Botha led "Dinuzulu's Volunteers", a group of Boers that had supported Dinuzulu against Zibhebhu in 1884. He later became a member of the parliament of Transvaal in 1897, representing the district of Vryheid.

In 1899, Botha fought in the Second Boer War, initially under Lucas Meyer in Northern Natal, and later as a general commanding and fighting impressively at Colenso and Spion Kop. On the death of P. J. Joubert, he was made commander-in-chief of the Transvaal Boers, where he demonstrated his abilities again at Belfast-Dalmanutha.

After the battle at the Tugela, Botha granted a twenty-four-hour armistice to General Buller to enable him to bury his dead.[2]

Winston Churchill revealed[3] that General Botha was the man who captured him at the ambush of a British armoured train on 15 November 1899. Coetzer 1996, p. 30 also claims that Botha captured Churchill at train ambush 15 November 1899. Churchill was not aware of the man's identity until 1902, when Botha travelled to London seeking loans to assist his country's reconstruction, and the two met at a private luncheon. The incident is also mentioned in Arthur Conan Doyle's book, The Great Boer War, published in 1902. But more recent sources claim that Field-Cornet Sarel Oosthuizen was in fact the Boer-soldier who, at gunpoint, captured Churchill.[4] Another version claims that the unit to capture Churchill was the Italian Volunteer Legion and its commander, Camillo Ricchiardi.[5]

After the fall of Pretoria in June 1900, Botha led a concentrated guerrilla campaign against the British together with Koos de la Rey and Christiaan de Wet. The success of his measures was seen in the steady resistance offered by the Boers to the very close of the three-year war.

Role after the Boer War

Botha was a representative of his countrymen in the peace negotiations of 1902, and was signatory to the Treaty of Vereeniging. After the grant of self-government to the Transvaal in 1907, General Botha was called upon by Lord Selborne to form a government, and in the spring of the same year he took part in the conference of colonial premiers held in London. During his visit to England on this occasion General Botha declared the whole-hearted adhesion of the Transvaal to the British Empire, and his intention to work for the welfare of the country regardless of (intra-white) racial differences (in this era referring to Boers/Afrikaners as a separate race to British South Africans).

He later worked towards peace with the British, representing the Boers at the peace negotiations in 1902. In the period of reconstruction under British rule, Botha went to Europe with de Wet and de la Rey to raise funds to enable the Boers to resume their former avocations.[6] Botha, who was still looked upon as the leader of the Boer people, took a prominent part in politics, advocating always measures which he considered as tending to the maintenance of peace and good order and the re-establishment of prosperity in the Transvaal. His war record made him prominent in the politics of Transvaal and he was a major player in the postwar reconstruction of that country, becoming Prime Minister of Transvaal on 4 March 1907.

In 1911, together with another Boer war hero, Jan Smuts, he formed the South African Party, or SAP. Widely viewed as too conciliatory with Britain, Botha faced revolts from within his own party and opposition from James Barry Munnik Hertzog's National Party. When South Africa obtained dominion status in 1910, Botha became the first Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa.

Later career

After the First World War started, he sent troops to take German South-West Africa, a move unpopular among Boers, which provoked the Boer Revolt.

At the end of the War he briefly led a British Empire military mission to Poland during the Polish-Soviet War. He argued that the terms of the Versailles Treaty were too harsh on the Central Powers, but signed the treaty. Botha was unwell for most of 1919. He was plagued by fatigue and ill-health that arose from his robust waist-line.[7] That he was fat is certain as related in the marvellous account of Lady Mildred Buxton asking General Van Deventer if he was bigger than Botha, to which Van Deventer replied: “I am longer, he is thicker.”[8] (In Afrikaans thicker literally means fatter, and does not differentiate between long and tall)

General Louis Botha died of heart failure following an attack of Spanish influenza on 27 August 1919 in the early hours of the morning. His wife Annie was at home and was joined by Engelenburg who had acted as a private secretary to Botha.[9][10] Botha was laid to rest in Heroes Acre Pretoria.

Of Botha, Winston Churchill wrote in Great Contemporaries, "The three most famous generals I have known in my life won no great battles over a foreign foe. Yet their names, which all begin with a 'B", are household words. They are General Booth, General Botha and General Baden-Powell..."[11]

Sculptor Raffaello Romanelli created the equestrian statue of Botha that stands outside The Union Buildings in Pretoria in South Africa.

References

- ↑ "Transvaal Cabinet Sworn In. Message from the Premier". Wanganui Herald. 6 March 1907. p. 6. Retrieved 2016-10-03 – via Papers Past.

- ↑ MacBride 2006, p. 43.

- ↑ Churchill 1996, p. 253.

- ↑ "Churchill, Sir Winston". Prominent people. 14 July 2013. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- ↑ Lupini, Mario. "Italian participation in the Anglo-Boer War". The South African Military History Society. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ "Boer Leaders Coming Here: Botha and De la Rey to Visit America" (PDF). The New York Times. 30 July 1902. p. 3.

- ↑ Engelenburg 1928, pp. 350 – 353.

- ↑ Meintjes 1970, p. 292.

- ↑ Engelenburg 1928, p. 355.

- ↑ Meintjes 1970, p. 302.

- ↑ Churchill 1948, p. 287.

Sources

- Churchill, Winston (1948) [1937]. Great Contemporaries. London: Odhams.

- Churchill, Winston (1996). My Early Life: 1874-1904. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-82345-4.

- Coetzer, Owen (1996). The Anglo-Boer War: The road to Infamy, 1899–1900. W. Waterman. ISBN 978-1-874959-10-6.

- Engelenburg, Frans Vredenrijk (1928). General Louis Botha. J.L. Van Schaik.

- MacBride, John (2006). Jordan, Anthony J., ed. Boer War to Easter Rising: The Writings of John MacBride. Westport. ISBN 978-0-9524447-6-3.

- Meintjes, Johannes (1970). General Louis Botha: a biography. Cassell.

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:- Peace of Vereeniging

- "Botha, Louis". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Louis Botha. |

Further reading

Biographical

- Spender, Harold (1916). General Botha, The Career And The Man. London: Constable.

Historical

- Farwell, Bryon (1976). The Great Boer War. London: Allen Lane. (insights of Botha)

- Williams, Basil (1946). Botha Smuts and South Africa. London: Hodder and Stoughton. (comprehensive commentaries on Smuts and Botha, or as William's titled them in the last chapter of this book par nobile fratrum:203

- C.J.Barnard (1970). Generaal Louis Botha Op Die Nataalse Front 1899-1900. Cape Town: A.A. Balkema.

Fiction

- O'Brien, Antony (2006). Bye-Bye Dolly Gray (illustrated ed.). Hartwell: Artillery Publishing. ISBN 9780975801321. (a heroic Boer character in this Australian/Boer War novel)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by ??? |

Member of South African Republic Parliament, Vryheid District 1897–1899 |

Succeeded by ??? |

| Preceded by New office |

Prime Minister, Transvaal 1907–1910 |

Succeeded by Merged with other territories to form Union of South Africa |

| Preceded by New office |

Prime Minister, Union of South Africa 1910–1919 |

Succeeded by Jan Smuts |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by New office |

Leader of the Het Volk Party 1907–1910 |

Succeeded by Merged with others to form South African Party |

| Preceded by New office |

Leader of the South African Party 1910–1919 |

Succeeded by Jan Smuts |

.svg.png)