Love in Several Masques

Love in Several Masques is a play by Henry Fielding that was first performed on 16 February 1728 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. The moderately received play comically depicts three lovers trying to pursue their individual beloveds. The beloveds require their lovers to meet their various demands, which serves as a means for Fielding to introduce his personal feelings on morality and virtue. In addition, Fielding introduces criticism of women and society in general.

The play marks Fielding's early approach to theatre and how he begins to create his own take on tradition 18th-century theatre conventions. Critics have emphasised little beyond how the play serves as Fielding's first play among many. The possible sources of the play including a possible failed pursuit of a lover by Fielding, or the beginnings of Fielding's reliance on the topic of gender, identity, and social ethics.

Background

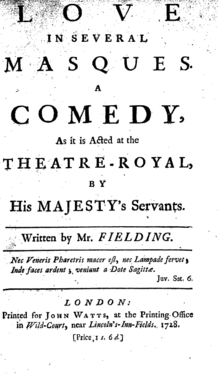

Love in Several Masques was Fielding's first play. It was advertised on 15 January 1728 in the London Evening Post and first ran on 16 February 1728 at the Theatre Royal. Performances were held on 17, 19 and 20 February, with the third night being the author's benefit. The play was never revived.[1] The cast included four members among some of the most talented of the Theatre Royal actors. Although it only ran for four nights, this was a great feat because John Gay's popular The Beggar's Opera was performed during the same time and dominated the theatrical community during its run.[2] It was first printed on 23 February 1728 by John Watts, and a Dublin edition appeared in 1728. The play was later collected by John Watts in the 1742 and 1745 Dramatick Works and by Andrew Millar in the 1755 edition of Fielding's works. It was later translated and printed in German as Lieb unter verschiedenen Larven in 1759.[3]

Most of the information on the play and its run is known because of Fielding's preface in the printed edition of the play. The printed Love in Several Masques is dedicated "To the Right Honourable the Lady Mary Wortley Montague", his cousin. It is probable that she read the original draft of the play, which is alluded to in the dedication.[4] Information on her reading the draft comes from a letter written in approximately September 1727.[5] In the letter, Fielding writes:

I have presum'd to send your Ladyship a Copy of the Play which you did me the Honor of reading three Acts of last spring: and hope it may meet as light a Censure from your Ladyship's Judgment as then: for while your Goodness permits me (what I esteem the greatest and indeed only Happiness of my Life) to offer my unworthy Performances to your Perusal, it will be entirely from your Sentence that they will be regarded or disesteem'd by Me.[6]

The play was completed during September 1727 and it was listed in the British Journal of 23 September 1727 as being scheduled. There is little information on Fielding's editing of the work, and none to support that anyone suggested corrections except Anne Oldfield, who he thanked in the Preface for supplying corrections. The prologue, dedication, and preface were probably composed during January or February 1728, with the dedication and preface most likely composed between the last nights of the show, 20 and 21 February, and its publication, 23 February.[7]

Cast

The cast according to the original printed billing:[8][9]

- Wisemore – lover of Lady Matchless, played by John Mills

- Merital – lover of Helena, played by Robert Wilks

- Malvil – lover of Vermilia, played by Bridgwater

- Lord Formal – rival to Wisemore, played by Griffin

- Rattle – fop and rival to Merital, played by Colley Cibber

- Sir Apish Simple – rival to Malvil, played by Josias Miller

- Lady Matchless – played by Anne Oldfield

- Vermilia – played by Mrs Porter

- Helena – played by Mrs Booth

- Sir Positive Trap – husband of Lady Trap, care taker of Helena, played by John Harper

- Lady Trap – played by Mrs. Moor

- Catchit – maid to Lady Trap, played by Mrs. Mills

- Prologue spoken by John Mills[10]

- Epilogue spoken by Miss Robinson, child actress[11]

Plot

The plot is traditional in regards to Restoration theatre and includes three female characters, three respectable males, three non-respectable males, and three side characters. Each respectable male meets their female counterpart three times, and each has a parallel incident with letters and an unmasking. The primary plot of the play deals with Wisemore and his pursuit of Lady Matchless.[12] With the help of his friend Merital, Wisemore is able to overcome other lovers and various struggles in order to prove his worth to Matchless and win her love.[13]

A secondary plot involves Merital and his desire to marry a woman named Helena, cousin to Matchless. He is kept from doing so externally by her uncle, Sir Positive Trap, by the workings of her aunt, and internally by themselves.[14] Against her uncles wishes, Helena and Merital elope. Although Trap is angered by this, Lady Matchless steps in and defends the marriage by saying that she too will marry like her cousin. The play ends with a song about beauty, virtue, and lovers.[15]

Preface

The printed version of the play included a self-conscious preface:[16]

I believe few plays have ever adventured into the world under greater disadvantage than this. First, as it succeeded a comedy which, for the continued space of twenty-eight nights, received as great (and as just) applauses, as ever were bestowed on the English Theatre. And secondly, as it is co-temporary with an entertainment which engrosses the whole talk and admiration of the town. These were difficulties which seemed rather to require the superior force of a Wycherley, or a Congreve, than of a raw and unexperienced pen; for I believe I may boast that none ever appeared so early upon the stage. However, such was the candour of the audience, the play was received with greater satisfaction than I should have promised myself from its merit, had it even preceded the Provoked Husband.[17]

He continued by thanking his cast, especially Anne Oldfield, for the effort that they put into their roles.[18] This preface served as a model for Fielding's later prefaces included in his novels, such as Joseph Andrews or Tom Jones.[16]

Themes

Love in Several Masques is a traditional comic drama that incorporates morality. The theme of the play is the relationship of disguises and courtship with a discussion of the nature of love. Fielding focuses on men and how they deal with love and marriage. Also, the gentlemen must prove their worth before they can be justified in their marriage, which allows Fielding to describe the traits required in successful male suitors. The first act deals primarily with the gentlemen in order to establish a focus on their characteristics.[19] Fielding's first play serves as a representation for his belief in the relationship of morality and libertine beliefs and introduces character types that he would use throughout his plays and novels.[20] However, all negative characteristics are very apparent to the audience, and those characters who are immoral are unable to accomplish their goals. The main characters are still decent individuals who are able to help another, even though they sometimes get in each other's way. At no time is the audience able to believe that vice will conquer, which undermines part of the satire. Regardless, Harold Pagliaro is still able to conclude that "Fielding's satire on the marriage market, however, is effective, if not biting."[21]

Wisemore's character introduces feelings about the London community and criticises various problems. However, his reflections are portrayed as both correct and lacking, and that he is focused only on the bad aspects of life. His ideas result from removing himself from society in preference to the company of classical books. Although he does not realise it, the play suggests that there are virtuous people. Merital, in response to Wisemore, believes that Wisemore's philosophical inclinations are foolish. As the play later reveals, Wisemore's views are only a mask to hide from his own feelings and views on love.[22]

Wisemore is not the only one to serve as a means to comment on society; the characters Vermilia and Lady Matchless are used to discuss the proper role of females within society by serving as housewives. The dialogue between the two reveals that females are only in control of the domestic sphere because men have allowed them to dominate in the area. This is not to suggest that Fielding supports the repression of females; instead, women are used as a way to discuss the internal aspects of humans including both emotions and morality. However, feminist critic Jill Campbell points out that Fielding does mock women who abuse their relationship with the internal, emotions, and morality in order to dominate and assume power.[23] Tiffany Potter, another feminist critic, sees gender within the play in a different light; Merital's actions and words show a moderate approach to females, and "Women are neither victims of deceitful men nor overdefensive virgins, but individuals who can choose to 'bestow' their favours on a man who will 'enjoy' them."[24]

The image of the masque within the play deals with hiding one's identity. Fielding, like many other playwrights, focuses on how the masque genre deals with the social acceptability of altering identities within the format. However, Fielding extends the image to discuss society and those who impersonate social and gender roles that they do not fill.[25] Fielding also has a problem with those who act viciously with license even though he is willing to accept some of the lesser libertine actions. Merital, for instance, is a sexual type of libertine and is treated differently than those like Sir Positive Trap, Lord Formal, and Sir Apish Simple who are criticised as being part of the corrupted order. Trap and Formal are part of old families, and their attachment to the age of their families and their attempts to use that to justify their beliefs over what is proper is ridiculed within the play. In particular, Merital is the one able to point out their flaws.[26]

Sources

It is possible that the plot of Love in Several Masques is connected to Fielding's own attempt to marry Sarah Andrew in November 1725.[27] Fielding met Andrew when he travelled to Lyme Regis. She was his cousin by marriage, 15 years old, and an heiress of the fortune of her father, Solomon Andrew. Her guardian Andrew Tucker, her uncle, prohibited Fielding from romantically pursuing her; it is possible that Tucker wished Andrew to marry his own son. On 14 November 1725, Andrew Tucker alleged the mayor that Fielding and Fielding's servant, Joseph Lewis, threatened to harm Tucker. According to Andrews's descendants, Fielding attempted to violently take Andrew on 14 November.[28] Regardless, Fielding fled the town after leaving a notice in public view that accused Andrew Tucker and his son of being "Clowns, and Cowards".[29] Thomas Lockwood qualified the connection of this incident and the plot of Love in Several Masques by saying, "I suspect so too, or at any rate suspect that this experience gave a crucial infusion of real feeling to that part of the play: which is however not to say that the writing itself, or the idea, goes back that far."[30]

The style of Love in Several Masques, along with The Temple Beau (1730), exemplified Fielding's understanding of traditional Post-Restoration comedic form.[31] Albert Rivero, a critic specialising in early 18th-century literature, believes that Fielding, in the play, "recognizes that to have his plays acted at Drury Lane, he must have the approval of his famous contemporary [Colley Cibber]. To gain that approval, Fielding must follow Cibber—if not write like him, certainly write plays that he will like."[32] However, Fielding did not respect Cibber's abilities, nor did he believe that the control Cibber took over the plays performed at the Theatre Royal were improved by Cibber's required changes. Instead, Fielding believed that Cibber got in the way of comedy.[33] Regardless, there are similarities between the characters in Love in Several Masques and Cibber and Vanbrugh's The Provok'd Husband. In particular, Fielding's Lady Matchless resembles the character Lady Townly.[34]

The play was traditionally believed by critics to be modelled after the plays of Congreve, with those in the eighteenth century, like Arthur Murphy, to those in the twentieth century, like Wilbur Cross, arguing in support of a connection. Love in Several Masques resembles Congreve's use of plot and dialogue. In particular, Merital and Malvil resemble characters in The Old Batchelor and Rattle resembles the fop in Love for Love. However, parts of Love in Several Masque also resembles Molière's Les Femmes Savantes, Sganarelle and Le Misanthrope. There are also possible connections between the play and Farquhar's The Constant Couple and Etherege's She wou'd if she Cou'd.[35] Of all the influences, theatre historian Robert Hume points out that Fielding's "play is humane comedy, not satire, and his generic affinities are closer to Centlivre and Cibber than to Congreve" and that "His first play is an imitative exercise in a popular form, not an attempt to write a Congrevean throw-back"; Hume offers that Love in Several Masques has connections to Christopher Bullock's Woman is a Riddle (1716), Susanna Centlivre's Busy Body (1709), Cibber's Double Gallant (1707), Farquhar's Constant Couple (1699), Richard Steele's Funeral (1701), John Vanbrugh's The Confederacy (1705) and The Mistake (1705) and Leonard Welsted's The Dissembled Wanton (1726).[36]

Critical response

Love in Several Masques was "neither a success nor a fiasco", and Fielding writes in the preface, "the Play was received with greater Satisfaction than I should have promised myself from its Merit".[37] The play was later quoted in The Beauties of Fielding more than any of Fielding's other plays, according to Thomas Lockwood, "because for anthology reading purposes it supplied far more extractably witty bits than other Fielding plays more representative or still holding the stage."[38]

Eighteenth and nineteenth century critics did little to discuss the play. David Erskine Baker simply lists the play in Companion to the Playhouse (1764), Charles Dibdin's History of the Stage (1800) makes a short comment on the dialogue, and John Genest said that the play was "moderate" in Some Account of the English Stage (1832).[39] A page is devoted to Love in Several Masques in Edwin Percy Whipple's review of a collection of Fielding's works, which calls the play "a well-written imitation" that has "smart and glib rather than witty" dialogue even though it contains "affected similes and ingenious comparisons, which the author forces into his dialogue to make it seem brilliant."[40] Frederick Lawrence, in his Life of Henry Fielding (1855), connected the play with those of Congreve and enjoyed some of the dialogue.[41]

Twentieth century critics tend to range in opinions on the play. F. Homes Dudden argues that "The dialogue is smart; the plot, though insufficiently compact, is fairly ingenious; the characters [...] are conventional comic types [...] It deserved what in fact it achieved—a qualified success."[42] Robert Hume believes that "The play is not, in truth, very good", that "Fielding offers three minimally intertwined love plots", and that the narrative is "clumsy".[43] However, Rivero believes that this characterisation is "unjust" and that the play deserves more merit. The play, as Rivero argues, "evinces what critics have identified as the quintessence of Fielding's art: its clear moral purpose, its conspicuous moral tone."[44] Thomas Lockwood argues that the play "has been noticed mainly as it was Fielding's first play, or else as the example of that imitation of Congrevean form which supposedly marked his beginning in dramatic authorship. Beyond these impressions of the play, there is no real tradition of critical discussion."[45] Pagliaro, one of Fielding's biographers, simply states that "By the standards of the day, the play neither failed nor succeeded, running four nights as it did."[46]

Notes

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 9

- ↑ Rivero 1989 pp. 6–7

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 10–14

- ↑ Hume 1988 pp. 29–30

- ↑ Battesin 1989 pp. 246–248

- ↑ Fielding 1993 p. 3

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 2–4

- ↑ Hume 1988 pp. 32–33

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 24

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 25

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 97

- ↑ Rivero 1989 p. 17

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 85–91

- ↑ Rivero 1989 pp. 17–18

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 91–95

- 1 2 Rivero 1989 p. 7

- ↑ Fielding 1902 Vol VIII p. 9

- ↑ Battestin and Battestin 1993 pp. 60–61

- ↑ Rivero 1989 pp. 16–17

- ↑ Potter 1999 p. 34

- ↑ Pagliaro 1998 pp. 58–59

- ↑ Rivero 1989 pp. 19–20

- ↑ Campbell 1995 pp. 23–24

- ↑ Potter 1999 p. 38

- ↑ Campbell 1995 pp. 49–50

- ↑ Potter 1999 pp. 36–37

- ↑ Cross 1918 pp. 53–55

- ↑ Battestin and Battestin 1993 pp. 49–50

- ↑ Battestin and Battestin 1993 qtd. p. 51

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 2

- ↑ Rivero 1989 p. 3

- ↑ Rivero 1989 p. 9

- ↑ Rivero 1989 p. 10

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 5

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 3–5

- ↑ Hume 1988 p. 31

- ↑ Hume 1988 qtd. p. 33

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 10

- ↑ Fielding 2004 pp. 10–11

- ↑ Whipple 1849 pp. 47–48

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 11

- ↑ Dudden 1966 p. 22

- ↑ Hume 1988 p. 30

- ↑ Rivero 1989 pp. 16–18

- ↑ Fielding 2004 p. 12

- ↑ Pagliaro 1998 p. 51

References

- Battestin, Martin. "Dating Fielding's Letters to Lady Mary Wortley Montagu" Studies in Bibliography 42 (1989).

- Battestin, Martin, and Battestin, Ruthe. Henry Fielding: a Life. London: Routledge, 1993.

- Campbell, Jill. Natural Masques: Gender and Identity in Fielding's Plays and Novels. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995.

- Cross, Wilbur. The History of Henry Fielding. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1918.

- Dudden, F. Homes (1966). Henry Fielding: his Life, Works and Times. Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books. OCLC 173325.

- Hume, Robert. Fielding and the London Theater. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.

- Fielding, Henry. The Complete Works of Henry Fielding. Ed. William Ernest Henley. New York: Croscup & Sterling co., 1902.

- Fielding, Henry. Plays Vol. 1 (1728–1731). Ed. Thomas Lockwood. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2004.

- Fielding, Henry. The Correspondence of Henry and Sarah Fielding. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Pagliaro, Harold. Henry Fielding: A Literary Life. New York: St Martin's Press, 1998.

- Potter, Tiffany. Honest Sins: Georgian Libertinism & the Plays & Novels of Henry Fielding. London: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1999.

- Rivero, Albert. The Plays of Henry Fielding: A Critical Study of His Dramatic Career. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989.

- Whipple, E. P. "Review" in North American Review. January 1849.