Malagasy pond heron

| Malagasy pond heron | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Ardeidae |

| Genus: | Ardeola |

| Species: | A. idae |

| Binomial name | |

| Ardeola idae (Hartlaub, 1860) | |

| |

The Malagasy pond heron (Ardeola idae) is a species of heron belonging to the Ardeidae family. They are primarily seen in the outer islands of the Seychelles, Madagascar and countries on the east coast of Africa such as Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda.[2] Being endemic to Madagascar, this species is often referred to as the Madagascar pond heron or Madagascar squacco heron.[3] The estimated population of this heron is thought to number 2,000–6,000 individuals, with only 1,300–4,000 being mature enough for reproductive activities.[4]

Taxonomy

The Malagasy pond heron was first described in 1860 by German physician and ornithologist Gustav Hartlaub.[5] His first sighting occurred on the east coast of Madagascar and as such the scientific name of Ardeola idae was formulated thereafter. Being a monotypic species it does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa.[6]

Description

Adult Malagasy pond herons grow to a length of 45–50 cm in height and anywhere from 250–350 grams in weight.[7] There is not a large variation in weight between the sexes as they are quite similar in bone body structure. In terms of feather, eye and bill colour the stage of life and reproductive status are the determining factors. The three stages of life are the adult, juvenile and the chick (young).

The adults appearance can be split into the non breeding plumage and the breeding stage. When the species is not breeding, the crown and the posterior are a colour mixture of buff and black with brown prominent over the other parts of the body.[8] The bill is predominately green with a black tip whilst the iris colour is yellow.[9] The flight feathers are clearly seen in flight and for the most part are white. Their lower mantle feathers and upper scapulars are loosely structured and elongated.[10] Moreover, the lower foreneck feathers are split into fine elongated tips, of which cover the upper breast.[11]

The primary difference of appearance in the breeding stage is the dominance of a snow white colour over the body.[12] Coupled with a bill of a deep azure blue the differences between the two adult types are clear. When coming out of breeding, an intermediate plumage emerges on the back. These new brown feathers are not the only change that occurs with dense plumes sprouting on areas such as the neck and breast.[13]

Prior to adulthood, the Malagasy pond heron will possess a juvenile plumage just before leaving the nest of which will last a few weeks.[14] The juvenile differs from the adult in having a dull orange bill and eyes of a pale green nature. The one distinguishing feature of the chick is its thick buff yellow down.[15]

Vocalisation

As they often hide in trees and shrubs at the sight of a human disturbance, distinguishing calls between species is often difficult. The Malagasy pond heron possesses two calls, a flight call and a burr call. The flight call has a duration of 0.5s and is used at 5 second intervals as a means to keep distances between other birds in flight.[16] Conversely, the burr call is often noted as the threat call which is used when rival herons approach the nest.[17]

Distribution and Habitat

As has been mentioned in the introductory paragraph, the Malagasy pond heron is distributed throughout the east of Africa in countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and Zambia.[18] They also range from the Secyhelles to Madagascar although they are rare in the south of the latter. In Madagascar, they are mostly observed at Lake Alarobia and Tsimbazaza Park (both in Antananarivo), wetlands around Ampijoroa and at Berenty.[19] As a result, their estimated area of occurrence is 553,000 square kilometres (214,000 sq mi). Ardeola idae occupy a broad range of Madagascan habitats that include small grassy marshes, lakes, ponds, streams and rice fields.[20] Those that populate the Aldabra region are commonly located in mangroves, inland pools and lagoon shores.[21] In the east of Africa it can inhabit fresh water marshes and streams of elevation levels up to 1,800 metres (5,900 ft). They are believed to inhabit anywhere from 11 to 100 locations in Madagascar and East Africa.

Behaviour

One of the key behavioural habits of the Malagasy pond heron is its yearly migratory pattern.[22] In May it will migrate from Madagascar to the eastern mainland of Africa and then journey back to its breeding range in October.[23] For those that have not matured into adult life they remain in the non breeding areas as there is no benefit in travelling to the breeding zone.

In terms of interaction, this species is very territorial and communication with other rival birds is limited.[24] As such, they will remain at least 10 metres apart if nesting or in flight due to their inconspicuous nature.[25] One observation found two Malagasy pond herons fighting, grasping at each others bills in the motion of flight. In Africa, instances such as this are scarce as there is rarely more than two on the same body of water.

Nesting is critical to the survival of this species so its behaviour in this area is well studied. Nesting tends to be done along the coast and the foraging for food is performed well inland away from the nests.[26] In fact, the closest that an individual heron will get to another apart from breeding is during roosting in their nests. Habitat degradation has resulted in closer roosting and has become integrated with other heron species such as Cattle Egrets and Squacco Herons.[27]

Diet

There is very limited knowledge on the feeding habits of the Madagascan pond heron but it is thought to feed solitarily on fish, insects and small invertebrates.[28] It may occasionally eat small reptiles such as skinks and geckos. In a small study of a single Malagasy heron in Madagascar, a diet of frogs, dragonflies, beetles and grasshoppers were observed.[29] Amphibians are for the most part absent on Aldabra and Mayotte so feeding on frogs are rare in these instances.

Threats

The main threat for survival of this species is the continual loss of habitat due to the clearing, drainage and conversion of their wetland environments to rice fields.[30] Moreover, should breeding be successful, the exploitation of eggs and young is prevalent at many of the breeding sites which can pose generational problems.[31] As a result, their population has declined dramatically over the last 50 years. However, a recently established resource management process labelled GELOSE has helped significantly decrease activity in this species habitat.[32]

An equally dangerous threat to their survival is competition with the squacco heron which are spreading vigorously and also seem to be more adaptable to man-made structures and icons that encroach on their habitat.[33] This form of heron greatly outnumbers the Malagasy pond heron in Madagascar and appears to have increased while endemic species has declined.[34] Although they are vastly outnumbered, the Malagasy pond heron is presumed to dominate in the interspecific interactions.

Breeding

The breeding of the Malagasy pond heron is colonial meaning that a large congregation occurs at a particular location for mating. However, both colony size and location numbers have dwindled over the past thirty years. Colony size has dropped from 700 individuals to around 50 whilst breeding locations are limited to only a few colony sites.[35] In Madagascar, colonies are located in phragmite reedbeds, typha, papyrus and cyprus stands with coastal islands being of extreme importance also.[36] Moreover, breeding in Madagascar results in a mixed colony of heron species that include but are not limited to the Black Crowned Night heron, Little egret, Cattle egret, Great egrets and the Squacco heron.[37] The largest colony of the Malagasy pond heron on record was around 500 pairs in Imerimanjaka Cyperus marsh, near Antananarivo.[38] These 500 pairs were also mixed with 1,500 pairs of Squacco herons resulting in the largest breeding colony of African herons in 1940.[39] Unfortunately, current day pairs usually never exceed 10.

Like many other bird species, the Malagasy pond heron faces an abundance of predators and as such must nest in trees and bushes in hard to access ponds and marshes. The main predator of this heron include the various species of crocodile that inhabit the range and also snakes should they grow large enough. To ward off ground threats, the breeding nests are built 1 to 4 metres above the ground.[40] Should the population colony be mixed with other avian species, they will always occupy the higher nests.[41]

Breeding usually starts in the month of October and can extend through to March should the heron be able to lay two clutches.[42] On the coral atoll of Aldabra, breeding increases markedly when the rains arrive during November and December.[43] Whilst the Malagasy pond heron has a large range of habitat, it will only breed in Madagascar and the aforementioned Aldabra. In Madagascar, the area to the west near Antananarivo is the preferred breeding location whereas the nature conservation sites of Ile aux Aigrettes and Ile aux Cedres of Aldabra are used.[44]

Successful breeding usually results from appropriate courtship displays which include features such as aerial chases, duets and crest raising. The incubation period is similar across all the breeding ranges and lasts anywhere from 21–25 days.[45] Normal young possess a green down which can be observed about 2 weeks after hatching when they leave the nest for the first time.[46]

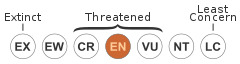

Conservation Status

The conservation status of the Malagasy pond heron has changed dramatically over the last 30 years. In 1988, this species was classified as near threatened according to IUCNs red list but changes to their habitat resulted in a move to the vulnerable category in 2000.[47] Consequently, as a result of further population decline their status ever since 2004 has been endangered.[48] It is listed as endangered as it has a very small population which is undergoing a continual decline due to the threats of young exploitation and wetland degradation.

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Ardeola idae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ 11

- ↑ 6

- ↑ 6

- ↑ 18

- ↑ 18

- ↑ 12

- ↑ 16

- ↑ 16

- ↑ 16

- ↑ 16

- ↑ 20

- ↑ 20

- ↑ 12

- ↑ 12

- ↑ 17

- ↑ 17

- ↑ 11

- ↑ 6

- ↑ 6

- ↑ 1

- ↑ 8

- ↑ 8

- ↑ 1

- ↑ 1

- ↑ 21

- ↑ 4

- ↑ 16

- ↑ 10

- ↑ 12

- ↑ 7

- ↑ 19

- ↑ 17

- ↑ 17

- ↑ 5

- ↑ 4

- ↑ 13

- ↑ 15

- ↑ 15

- ↑ 14

- ↑ 4

- ↑ 20

- ↑ 3

- ↑ 3

- ↑ 12

- ↑ 14

- ↑ 2

- ↑ 2

- ↑ Benson, C., & Penny, M. (1971). The land birds of Aldabra. Philosophical Transactions Of The Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 260(836), 417-527.

- ↑ Boere, G., Galbraith, C., & Stroud, D. (2006). Waterbirds around the world. Edinburgh: The Stationery Office.

- ↑ Bunbury, N. (2013). Distribution, seasonality and habitat preferences of the endangered Madagascar Pond-heron Ardeola idae on Aldabra Atoll: 2009-2012. Ibis, 156(1), 233-235.

- ↑ Burger, J. (1990). Vertical nest stratification in a heronry in Madagascar. Colonial Waterbirds 13(2), 143-146.

- ↑ Collar, N., Crosby M., & Stattersfield A. (1994). Birds to Watch 2. The World Checklist of Threatened Birds. Cambridge: International Council for Bird Preservation.

- ↑ Dee, T. (1986). The endemic birds of Madagascar. Cambridge, England: ICBP.

- ↑ Dodman, T. (2002). Waterbird Population Estimates in Africa. Report to Wetlands International.

- ↑ Goodman, S., & Patterson, B. (1997). Natural change and human impact in Madagascar. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- ↑ Hoyo J., Elliot, A., Sargatal, J., & Cabot, J. (1992). Handbook of the birds of the world. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions.

- ↑ Hustler, K., & Marshall, B. (1996). The abundance and food consumption of piscivorous birds on Lake Kariba, Zimbabwe-Zambia. Ostrich, 67(1), 23-32.

- ↑ Kushlan, J., & Hafner, H. (2000). Heron conservation. San Diego: Academic Press

- ↑ Kushlan, J., & Hancock, J. (2005). Herons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Kushlan, J. (2008). Conserving herons. Arles, France: Tour du Valat.

- ↑ Langrand, O. (1990). Guide to the birds of Madagascar. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ↑ Milon, P. (1949). Les crabiers de la campagne de Tananarive. Naturaliste Malgache 1: 3-9.

- ↑ Morris, P., & Hawkins, F. (1998). Birds of Madagascar. Mountfield: Pica Press.

- ↑ Ndang’ang’a, P.K. And Sande, E. (Compilers). 2008. International Single Species Action Plan for the Madagascar Pond-heron (Ardeola idae). CMS Technical Series No. 20, AEWA Technical Series No. 39. Bonn, Germany.

- ↑ Newton, A. (1877). Hartlaub’s “Birds of Madagascar”. Nature, 17(418), 9-10.

- ↑ Razafimanjato, G., Sam, T., & Thorstrom, R. (2007). Waterbird Monitoring in the Antsalova Region, Western Madagascar. Waterbirds, 30(3), 441-447.

- ↑ Salvan, J. (1972). Statut, recensement, reproduction des oiseaux dulcaquicoles aux environs de Tananarive. L’Oiseau et R.F.O, 42, 35-51.

- ↑ Wilme, L., & Jacquet, C. (2002). Census of waterbirds and herons nesting at Tsarasaotra (Alarobia), Antananarivo, during the second semester of 2001. Working group on birds in the Madagascar region, 10(1), 14-21.