Maggi Hambling

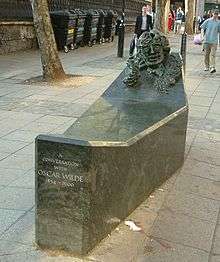

Maggi Hambling CBE (born 23 October 1945 in Sudbury, Suffolk[1]) is a British contemporary painter and sculptor. Perhaps her best-known public works are a sculpture for Oscar Wilde in central London and Scallop, a 4-metre-high steel sculpture on Aldeburgh beach dedicated to Benjamin Britten. Both works have attracted a great degree of controversy.[2]

Biography

Hambling studied at the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing from 1960 under Cedric Morris and Lett Haines, then at Ipswich School of Art (1962–64), Camberwell (1964–67), and finally the Slade School of Art, graduating in 1969.[3] In 1980 Hambling became the first Artist in Residence at the National Gallery, London, after which she produced a series of portraits of the comedian Max Wall. Wall responded to Hambling's request to paint him with a letter saying: "Re: painting little me, I am flattered indeed – what colour?"[1][4] She has taught at Wimbledon School of Art.[5]

In 1995, she was awarded the Jerwood Painting Prize (with Patrick Caulfield). In the same year she was awarded an OBE for her services to painting, followed by a CBE in 2010. Hambling's celebrated series of North Sea paintings have continued since late 2002.

Portraits form part of Hambling's oeuvre, with several works in the National Portrait Gallery, London.[6] Women feature prominently in her portrait series. For example, Hambling was commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery to paint Professor Dorothy Hodgkin in 1985. The portrait features the Professor Hodgkin at at desk with four hands all engaged in different tasks.[7] Her wider body of work is held in many public collections including the British Museum, Tate Collection, National Gallery, Scottish Gallery of Modern Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In 2013, she exhibited at Snape during the Aldeburgh Festival, and a solo exhibition was held at the Hermitage, St Petersburg.

Hambling is openly "lesbionic" (her adjective).[8] In 1998, she met and created charcoal portraits of her partner Henrietta Moraes in the last year of her life.[9] The Telegraph obituary for the racing journalist Lord Oaksey recorded that, " The marriage broke up in unhappily public fashion in the mid-1980s, when Lady Oaksey left her husband for the artist Maggi Hambling".[10]

As of November 2016 she lives with her partner of 33 years, fellow artist Tory Lawrence in a cottage near Saxmundham in Suffolk.[11]

With regard to Scallop the artist describes the sculpture as a conversation with the sea:

- "An important part of my concept is that at the centre of the sculpture, where the sound of the waves and the winds are focused, a visitor may sit and contemplate the mysterious power of the sea."[12]

Personal life

Hambling gave up smoking in 2004 and was involved in the campaign against the total ban on smoking in public places in England which took effect on 1 July 2007. Speaking at a news conference at the House of Commons on 7 February 2007, she said: "I wholeheartedly support the campaign against a ban on smoking in public places. Just because I gave up at 59, other people may choose not to. There must be freedom of choice, something that is fast disappearing in this so-called free country."[13]

She took up smoking again on her 65th birthday but only 'the ones that smell of toothpaste'.[11]

In August 2014, Hambling was one of 200 public figures who were signatories to a letter to The Guardian opposing Scottish independence in the run-up to September's referendum on that issue.[14]

Footnotes

- 1 2 Bredin, Lucinda (18 May 2002). "A matter of life and death". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev (3 November 2003). "A word in your shell-like: get that monstrosity off our beach". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ "Maggi Hambling biography". Tate Gallery. 2006. Retrieved 2006-06-01.

- ↑ Clark, Alex (22 January 2006). "Hambling for the defence". Observer Review & Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ Wimbledon College of Art: About Wimbledon: Alumni: Alumni List. University of the Arts London. Accessed August 2013.

- ↑ "Maggi Hambling (1945–), Painter". National Portrait Gallery. 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- ↑ Foster, Alicia (2004). Tate Women Artistis. London: Tate Publishing. pp. 204–205. ISBN 1-85437-311-0.

- ↑ "Maggi Hambling: 'I was put forward to paint the Queen Mother but the word came back saying I was a bit risky'". The Independent. 1 May 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ↑ Berger, John (2001). The last 235 days. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 07475 5589 3.

- ↑ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/sport-obituaries/9522348/Lord-Oaksey.html

- 1 2 A Life in the Day: Maggi Hambling, artist | The Sunday Times Magazine Retrieved 2016-11-05.

- ↑ "Scallop: a celebration of Benjamin Britten". OneSuffolk. Archived from the original on 2006-08-31. Retrieved 2006-06-01.

- ↑ "Opposition to total smoking ban widens". Forest - Freedom Organisation for the Right to Enjoy Smoking Tobacco. 2007. Archived from the original on 2006-12-08. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- ↑ "Celebrities' open letter to Scotland – full text and list of signatories | Politics". theguardian.com. 2014-08-07. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

References

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maggi Hambling. |

- Lynn Barber, A Life in Pictures, The Interview: Maggi Hambling, The Observer, 2 December 2007

- BBC Video Nation: Maggi Hambling & The Sea, 2009