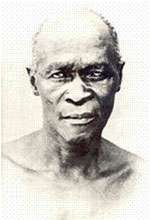

Maqoma

| Chief Maqoma | |

|---|---|

Chief Maqoma | |

| Born |

1798 Rharhabe |

| Died |

1873, age 75 Robben Island |

| Cause of death | Old age, combined with poor treatment at Robben Island |

| Nationality | South African |

| Occupation | Warrior, military commander |

| Known for | Commanding the Xhosa military forces in the Sixth and Eighth Xhosa Wars. |

| Parent(s) | Ngqika, King of the Rharhabe division of the Xhosa nation |

Maqoma (1798–1873) was a Xhosa warrior. Amongst the greatest of Xhosa military commanders, he played a major part in the Sixth and Eighth Xhosa Wars.[1]

Early life

Born in the right-hand house of Xhosa chief Ngqika, King of the Rharhabe division of the Xhosa people. Throughout his life, he was opposed to his father's strategy of ceding land to the Cape Colony; as a result, in 1822, he went back into the Neutral Zone in order to establish his own chiefdom.

Sixth Xhosa War

The Sixth War is known as Hintsa's War by the Xhosa. However, Hintsa did not instigate the war and, although he gave support to the Xhosa armies which were involved, it was Chief Maqoma who was the primary leader of the Xhosa forces.

Background

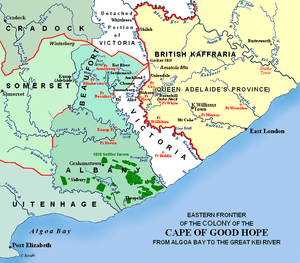

On the Cape's eastern border (now the Keiskamma River) insecurity persisted. Particularly as the Xhosa on the other side of the border were under considerable pressure from forces further east such as the effects of the expanding Zulu Empire. Although highly unstable, the frontier region was seeing increasing amounts of cultural diversity, with Europeans, Khoikhoi and Xhosa living and trading throughout the frontier region.

Outbreak

Local Cape responses to the Xhosa cattle raids varied, but in some cases were drastic and violent. On 11 December 1834, a Cape government commando party killed a chief of high rank, incensing the Xhosa: an army of 10,000 men, led by Maqoma, swept across the frontier into the Cape Colony, pillaged and burned the homesteads and killed all who resisted. Among the worst sufferers was a colony of freed Khoikhoi who, in 1829, had been settled in the Kat River valley by the British authorities. Refugees from the farms and villages took to the safety of Grahamstown, where women and children found refuge in the church.

British campaign

The response was swift and multi-faceted. Boer commandos mobilised under Piet Retief and inflicted a defeat on the Xhosa in the Winterberg Mountains in the north. Burgher and Khoi commandos also mobilised, and British Imperial troops arrived via Algoa Bay.

The British governor, Sir Benjamin d'Urban mustered the combined forces under Colonel Sir Harry Smith, who reached Grahamstown on 6 January 1835, six days after news of the uprising had reached Cape Town. It was from Grahamstown that the retaliatory campaign was launched and directed.

The campaign inflicted a string of defeats on the Xhosa, such as at Trompetter's Drift on the Fish River, and most of the Xhosa chiefs surrendered. However Maqoma and Tyali (the other major Xhosa leader) retreated to the fastnesses of the Amatola Mountains.

The treaty

British governor Sir Benjamin d'Urban believed that Hintsa ka Khawuta, Paramount-Chief of the Gcaleka Xhosa, commanded authority over all of the Xhosa tribes and therefore held him responsible for the initial attack on the Cape Colony, and for the looted cattle. D'Urban came to the frontier in December 1834, and led a large force across the Kei river to confront Hintsa at his residence and dictate terms to him.

The terms dictated that all the country from the Cape's prior frontier, the Keiskamma River, as far as the Great Kei River was annexed as the British "Queen Adelaide Province", and its inhabitants declared British subjects. A site for the seat of province's government was selected and named King William’s Town. The new province was declared to be for the settlement of loyal tribes, rebel tribes who replaced their leadership, and the Fengu (known to the Europeans as the "Fingo people"), who had recently arrived fleeing from the Zulu armies and had been living under Xhosa subjection. Magistrates were appointed to administer the territory in the hope that they would gradually, with the help of missionaries, undermine tribal authority. Hostilities finally died down on 17 September 1836, after having continued for nine months.

Eighth Xhosa War

Background

Large numbers of Xhosa were displaced across the Keiskamma by Governor Harry Smith, and these refugees supplemented the original inhabitants there, causing overpopulation and hardship. Those Xhosa who remained in the colony were moved to towns and encouraged to adopt European lifestyles.

Harry Smith also attacked and annexed the independent Orange Free State, hanging the Boer resistance leaders, and in the process alienating the Burghers of the Cape Colony. To cover the mounting expenses he then imposed exorbitant taxes on the local people of the frontier and cut the Cape's standing forces to less than five thousand men.

In June 1850 there followed an unusually cold winter, together with an extreme drought. It was at this time that Smith ordered the displacement of large numbers of Xhosa squatters from the Kat River region.

The Outbreak of War (December 1850) Governor Sir Harry Smith travelled to meet with the prominent chiefs after unrest in the Xhosa nation. When Sandile refused to attend a meeting outside Fort Cox, Governor Smith deposed him and declared him a fugitive. On 24 December, a British detachment of 650 men under Colonel Mackinnon was ambushed by Xhosa warriors in the Boomah Pass. The party was forced to retreat to Fort White, under heavy fire from the Xhosa, having sustained forty-two casualties. The very next day, during Christmas festivities in towns throughout the border region, apparently friendly Xhosa entered the towns to partake in the festivities. At a given signal though, they fell upon the settlers who had invited them into their homes and killed them. With this attack, the bulk of the Ngqika joined the war.

Initial Xhosa victories

While the Governor was still at Fort Cox, the Xhosa forces advanced on the colony, isolating him there. The Xhosa burned British military villages along the frontier, and captured the post at Line Drift. Meanwhile, the Khoi of the Blinkwater River Valley and Kat River Settlement revolted, under the leadership of a half-Khoi, half-Xhosa chief Hermanus Matroos, and managed to capture Fort Armstrong. Large numbers of the "Kaffir Police" — a paramilitary police force the British had established to combat cattle theft — deserted their posts and joined Xhosa war parties. For a while, it appeared that all of the Xhosa and Khoi people of the eastern Cape were taking up arms against the British.

Harry Smith finally fought his way out of Fort Cox with the help of the local Cape Mounted Riflemen, but found that he had alienated most of his local allies. His policies had made enemies of the Burghers and Boer Commandos, the Fengu, and the Khoi, who formed much of the Cape's local defences. Even some of the Cape Mounted Riflemen refused to fight.[2]

British counter-attack (Jan 1851)

After these initial successes, however, the Xhosa experienced a series of setbacks. Xhosa forces were repulsed in separate attacks on Fort White and Fort Hare. Similarly, on 7 January, Hermanus and his supporters launched an offensive on the town of Fort Beaufort, which was defended by a small detachment of troops and local volunteers. The attack failed however, and Hermanus was killed. The Cape Government also eventually agreed to levy a force of local gunmen (predominantly Khoi) to hold the frontier, allowing Smith to free some imperial troops for offensive action.[3]

British reinforcements

By the end of January, the British were beginning to receive reinforcements from Cape Town and a force under Colonel Mackinnon was able to successfully drive north from King William's Town to resupply the beleaguered garrisons at Fort White, Fort Cox and Fort Hare. With fresh men and supplies, the British expelled the remainder of Hermanus' rebel forces (now under the command of Willem Uithaalder) from Fort Armstrong and drove them west toward the Amatola Mountains. Over the coming months, increasing numbers of Imperial troops arrived, reinforcing the heavily outnumbered British and allowing Smith to lead sweeps across the frontier country.

In 1852, HMS Birkenhead was wrecked at Gansbaai while bringing reinforcements to the war at the request of Sir Harry Smith. As the ship sank, the men (mostly new recruits) stood silently in rank, while the women and children were loaded into the lifeboats. They remained in rank as the ship slipped under and over 300 died.

Final stages of the conflict

Insurgents led by Maqoma established themselves in the forested Waterkloof. From this base they managed to plunder surrounding farms and torch the homesteads. Maqoma's stronghold was situated on Mount Misery, a natural fortress on a narrow neck wedged between the Waterkloof and Harry's Kloof. The Waterkloof conflicts lasted two years. Maqoma also led an attack on Fort Fordyce and inflicted heavy losses on the forces of Sir Harry Smith.

In February 1852, the British Government decided that Sir Harry Smith's inept rule had been responsible for much of the violence, and ordered him replaced by George Cathcart, who took charge in March. For the last 6 months, Cathcart ordered scourings of the countryside for rebels. In February 1853, Sandile and the other chiefs surrendered.

The 8th frontier war was the most bitter and brutal in the series of Xhosa wars. It lasted over two years and ended in the complete subjugation of the Ciskei Xhosa.[4]

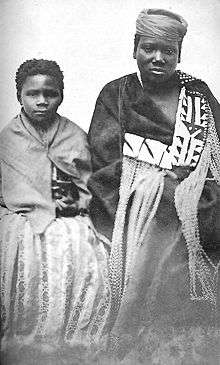

Imprisonment

Maqoma was twice prisoner at Robben Island. During the first term, he was allowed company with his wife and son. However, on the second term, at the age of seventy-three, he was sent there alone. A visiting Anglican chaplain witnessed his last moments in 1873, when he "cried bitterly, before dying of old age and dejection".[5]

See also

References

- ↑ "Chief Maqoma". South African History Online. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ↑ Abbink & Peires 1989, p. .

- ↑ Abbink, Bruijn & Walraven 2008, p. .

- ↑ Stapleton, Timothy J. (1993). "The Memory of Maqoma". History in Africa. 20: 321–335. doi:10.2307/3171978.

- ↑ Meredith, Martin (1997). Mandela: A Biography. Public Affairs Books. p. 7.