Molly Pitcher

| Molly Pitcher | |

|---|---|

Molly Pitcher at the Battle of Monmouth, lithograph | |

| Birth name | Mary Ludwig Hays |

| Born |

October 13, 1754 Trenton, New Jersey, British America |

| Died |

January 22, 1832 (aged 77) Carlisle, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Allegiance |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| Spouse(s) |

|

Molly Pitcher was a nickname given to a woman said to have fought in the American Battle of Monmouth, who is generally believed to have been Mary Ludwig Hays. Since various Molly Pitcher tales grew in the telling, many historians regard Molly Pitcher as folklore rather than history, or suggest that Molly Pitcher may be a composite image inspired by the actions of a number of real women. The name itself may have originated as a nickname given to women who carried water to men on the battlefield during War.

Mary Ludwig Hays

The deeds in the story of Molly Pitcher are generally attributed to Mary Ludwig Hays.[1] Molly was a common nickname for women named Mary in the Revolutionary time period. Biographical information about Mary Hays has been gathered by descendant-historians,[2] including her cultural heritage, given name, probable year of birth, marriages, progeny, census and tax records, etc., suggesting a reasonably reliable account of her life. Nonetheless, independent review of these documents and the conclusions suggested by the family still needs to be done by professional historians; some details of her life and evidence of the story of her heroic deeds remain sparse.

Mary Ludwig was born to a family in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There is some dispute over her actual birth date. A marker in the cemetery where she is buried lists her birth date as October 13, 1744.[3] Mary had a moderately sized family that included her older brother Johann Martin, and their parents, Maria Margaretha and Johann George Ludwig, who was a butcher. It is likely that she never attended school or learned to read, as education was considered a waste of money on young girls at this time.[4]

Johanes George Ludwick died in January, 1769, and the following June, his widow, Mary Ludwick (also "Ludwig") married John Hays. In early 1777, Molly married William Hays, a barber, in the town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Continental Army records show that William Hayes was an artilleryman at the Battle of Monmouth in 1778. On July 12, 1774, in a meeting in the Presbyterian Church in Carlisle, Dr. William Irvine organized a boycott of British goods as a protest of the Tea Act. William Hays' name appears on a list of people who were charged with enforcing the boycott.[4]

Valley Forge

In 1777, William Hays enlisted in Proctor's 4th Pennsylvania Artillery, which later became Proctor's 4th Artillery of the Continental Army. During the winter of 1777, Mary Hays joined her husband at the Continental Army's winter camp at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. She was one of a group of women, led by Martha Washington, known as camp followers, who would wash clothes and blankets, and care for sick and dying soldiers.

In the late winter and spring of 1778, the Continental Army trained under Baron von Steuben. William Hays trained as an artilleryman, and Mary Hays and other camp followers served as water carriers, carrying water to troops who were drilling on the field. Also, artillerymen needed a constant supply of fresh water to cool down the hot cannon barrel, and to soak the sponge on the end of the ramrod, the long pole which was used to clean sparks and gunpowder out of the barrel after each shot. It was during this time that Mary Hays probably received her nickname, as troops would shout, "Molly! Pitcher!" whenever they needed her to bring fresh water.

Battle of Monmouth

At the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778, Mary Hays attended to the Revolutionary soldiers by giving them water. Just before the battle started, she found a spring to serve as her water supply. Two places on the battlefield are currently marked as the "Molly Pitcher Spring." Mary Hays spent much of the early day carrying water to soldiers and artillerymen, often under heavy fire from British troops.

The weather was hot, over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Sometime during the battle, William Hays collapsed, either wounded or suffering from heat exhaustion. It has often been reported that Hays was killed in the battle, but it is known that he survived.[4]

As her husband was carried off the battlefield, Mary Hays took his place at the cannon. For the rest of the day, in the heat of battle, Mary continued to "swab and load" the cannon using her husband's ramrod. At one point, a British musket ball or cannonball flew between her legs and tore off the bottom of her skirt. Mary supposedly said something to the effect of, "Well, that could have been worse," and went back to loading the cannon.[5]

Joseph Plumb Martin recalls this incident in his memoirs, writing that at the Battle of Monmouth, "A woman whose husband belonged to the artillery and who was then attached to a piece in the engagement, attended with her husband at the piece the whole time. While in the act of reaching a cartridge and having one of her feet as far before the other as she could step, a cannon shot from the enemy passed directly between her legs without doing any other damage than carrying away all the lower part of her petticoat. Looking at it with apparent unconcern, she observed that it was lucky it did not pass a little higher, for in that case it might have carried away something else, and continued her occupation."

Later in the evening, the fighting was stopped due to gathering darkness. Although George Washington and his commanders expected the battle to continue the following day, the British forces retreated during the night and continued on to Sandy Hook, New Jersey.

After the battle, General Washington asked about the woman whom he had seen loading a cannon on the battlefield. In commemoration of her courage, he issued Mary Hays a warrant as a non commissioned officer. Afterwards, she was known as "Sergeant Molly," a nickname that she used for the rest of her life.[5]

Later life and death

Following the end of the war, Mary Hays and her husband William returned to Carlisle, Pennsylvania. During this time, Mary gave birth to a son named Johanes (or John).[4] In late 1786, William Hays died.

In 1793, Mary Hays married John McCauley, another Revolutionary War veteran and possibly a friend of William Hays. McCauley was a stone cutter for the local Carlisle prison. However, the marriage was reportedly not a happy one, as McCauley had a violent temper. It was McCauley who was the cause of Mary's financial downfall, causing Mary to sell 200 acres of bounty land left to her by William Hays, for 30 dollars. Sometime between 1807 and 1810, McCauley disappeared, and it is not known what happened to him.

Mary McCauley continued to live in Carlisle. She earned her living as a general servant for hire, cleaning and painting houses, washing windows, and caring for children and sick people. "Sergeant Molly," as she was known, was often seen in the streets of Carlisle wearing a striped skirt, wool stockings, and a ruffled cap.[4] She was well liked by the people of Carlisle, even though she "often cursed like a soldier." [5]

On February 21, 1822, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania awarded Mary McCauley an annual pension of $40 for her service. Mary died January 22, 1832, in Carlisle, at the approximate age of 78.[6] She is buried in the Old Graveyard in Carlisle, under the name "Molly McCauley" and statue of "Molly Pitcher," standing alongside a cannon, stands in the cemetery.[3]

Margaret Corbin

The story of Margaret Corbin bears similarities to the story of Mary Hays. Margaret Corbin was the wife of John Corbin of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, also an artilleryman in the Continental army. On November 16, 1776, John Corbin was one of 2,800 American soldiers who defended Fort Washington in northern Manhattan from 9,000 attacking Hessian troops under British command. When John Corbin was wounded and killed, Margaret took his place at the cannon, and continued to fire it until she was seriously wounded in the arm. In 1779, Margaret Corbin was awarded an annual pension of $50 by the state of Pennsylvania for her heroism in battle. She was the first woman in the United States to receive a military pension. Her nickname was "Captain Molly".[4]

Commemorations

Federal

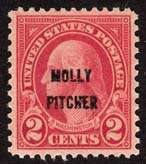

In 1928, "Molly Pitcher" was honored with an overprint reading "MOLLY / PITCHER" on a United States postage stamp. Earlier that year, festivities had been planned to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Monmouth. Stamp collectors petitioned the U.S. Post Office Department for a commemorative stamp to mark the anniversary. After receiving several rejections, New Jersey congressman Ernest Ackerman, a stamp collector himself, enlisted the assistance of the majority leader of the House, John Q. Tilson.[7] Postmaster General Harry New steadfastly refused to issue a commemorative stamp specifically acknowledging the battle or Molly Pitcher. In a telegram to Tilson, Postmaster New explained, "Finally, however, I have agreed to put a surcharged title on ten million of the regular issue Washington 2¢ stamps bearing the name 'Molly Pitcher.'"[7]

Molly was finally pictured on an imprinted stamp on a postal card issued in 1978 for the 200th anniversary of the battle.[8]

"Molly" was further honored in World War II with the naming of the Liberty ship SS Molly Pitcher, launched, and subsequently torpedoed, in 1943.

The stretch of US Route 11 between Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, and the Pennsylvania-Maryland state line is known as the Molly Pitcher Highway.

The Field Artillery and Air Defense Artillery branches of the US Army established an honorary society in Molly Pitcher's name, the Honorable Order of Molly Pitcher. Membership is ceremoniously bestowed upon wives of artillerymen during the annual Feast of St. Barbara. The Order of Molly Pitcher recognizes individuals who have voluntarily contributed in a significant way to the improvement of the Field Artillery community.

The U.S. Army base Fort Bragg holds an annual event called "Molly Pitcher Day," showcasing weapon systems, airborne operations, and field artillery for family members.

Other

There is a hotel in Red Bank, New Jersey, not far from the site of the Battle of Monmouth, called the Molly Pitcher Inn. The State of Tennessee became the second State in the Union (preceded by West Virginia) to offer their women veterans a license plate honoring their service. The plate depicts Molly Pitcher, recognizing women in combat from the beginnings of the nation. On I-95 (New Jersey Turnpike) a service area is named Molly Pitcher Service Area in Cranbury Township, New Jersey

See also

- Anna Maria Lane

- Agustina de Aragón

- Deborah Sampson

- Francisca Carrasco Jimenez

- Giuseppa Bolognara Calcagno

- Molly Corbin

References

- ↑ Will the Real Molly Pitcher Please Stand Up? Teipe, Emily J.

- ↑ The Real Pennsylvania Dutch American, "Molly Pitcher"

- 1 2 Molly Pitcher – Original name: Mary Ludwig Hayes McCaauley at Find a Grave

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Koestler-Grack, Rachel A. Molly Pitcher: Heroine of the War for Independence. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2006. ISBN 0-7910-8622-4.

- 1 2 3 Rockwell, Anne They Called Her Molly Pitcher. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002. ISBN 0-679-89187-0.

- ↑ "Pitcher, Molly." Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 February 2007.

- 1 2 Hotchner, William M. (2008-08-25). "The scandal surrounding the Molly Pitcher overprint stamp of 1928". Linn's Stamp News. Amos Press Inc. p. 6.

- ↑ United States Postal Cards UX77, multicolored, lithographed, issued September 8, 1978, in Freehold, New Jersey. Bicentennial of the Battle of Monmouth on June 28, 1778, and to honor Molly Pitcher (Mary Ludwig Hays)

Bibliography

- Bilby, Joseph G., and Katherine Bilby Jenkins. Monmouth Court House: The Battle That Made the American Army. Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2010. ISBN 9781594161087 OCLC 495778701

- Downey, Fairfax. 1956. "The Girls Behind the Guns". American Heritage. 8, no. 1: 46-48.

- Bohrer, Melissa Lukeman. Glory, Passion, and Principle: The Story of Eight Remarkable Women at the Core of the American Revolution. New York: Atria Books, 2003. ISBN 0-7434-5330-1.

- Raphael, Ray. Founding Myths: Stories That Hide Our Patriotic Past. New York: New Press, 2004. ISBN 1-56584-921-3. Raphael regards "Molly Pitcher" as a myth that serves to obscure the actual (though less dramatic) contributions of women to the war effort.

- The Real Pennsylvania Dutch American, "Molly Pitcher" – A Documented History. ISBN 1-4685-1019-3.

| Library resources about Molly Pitcher |

External links

- Molly Pitcher Overprint on 2¢ Postage Stamp

- Tugster Blog of Molly Pitcher Rest Area on the New Jersey Turnpike

-

"Molly, Captain". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

"Molly, Captain". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.