Masculine psychology

Masculine psychology may refer to the gender-related psychology of male human identity. One stream of thought emphasizes gender differences and has a scientific and empirical approach, while the other, more therapeutic in orientation, is more closely aligned to the psychoanalytic tradition. It also relates to concepts such as masculinity and machismo.

Attaining manhood

Jungian analysts Guy Corneau and Eugene Monick argue that the establishment and maintenance of the male identity is more delicate and fraught with complication than that of the establishment and maintenance of the female identity. Such psychologists suggest that this may be because men are born of the female body, and thus are born from a body that is a different gender from themselves. Women, on the other hand, are born from a body that is the same gender as their own. Camille Paglia declares: A woman simply is, but a man must become. Masculinity is risky and elusive. It is achieved by a revolt from woman, and it is confirmed only by other men. Manhood coerced into sensitivity is no manhood at all.[1]

Role of the father

Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung argued that a father is very important to a boy's development of identity. In his book Absent Fathers, Lost Sons[2] Canadian Jungian analyst Guy Corneau writes that the presence of the father's body during the son's developmental phases is integral in the son developing a positive sense of self as masculine. Corneau also argues that if the son does not develop positively towards the father's male body, then the son runs the risk of developing negatively towards all bodies. Jacques Lacan argued that in the son's mind, the father's body represents the law, and that the role of the father's body is to break the attachment the son feels to the mother and by extension his own.

Freudian analysts claim that all sons feel they are in competition with their father and often feel in a battle against the father. This is well represented in Greek mythology as Chronos, the father of the gods, is in constant war with his children should they contradict him.[3] This dominant patriarchal attitude still has roots in society today as men are viewed to be heads of families. (Sigmund Freud referred to this as Oedipus complex.) Freudian psychologists claim that the risk the son runs is that in some cases it is more difficult to win the battle against the father than to lose the battle against the father. This is because a common result of winning the battle against the father is that the son suffers tremendous guilt.

Influence on religion

Gender of God

The original languages of several religions have gender-specific pronouns or verb conjugation. References to God often use the masculine pronoun "He," and in other ways refer to God as masculine. In many religions, including Judaism, Sikhism, and Islam, God has traditionally been referred to by using masculine pronouns. However, in the original Hebrew and Aramaic languages of the Old Testament, God is referred to by a variety of names, in both singular and plural forms, and so it is not clear that the use of a masculine pronoun necessarily conveys actual gender. For example, in Sikhism the use of masculine pronouns is due to grammatical conventions and does not signify actual gender. In Islam, similarly, God is generally depicted as having a male gender, though there may be debate as to God's gender. As there is no neutral gender in Arabic, God is referred to in the masculine form by default, and it is universally understood that God (Allah) is not a woman.[4]

In Mainstream Christianity God is understood as a Trinity of three persons in one God, consisting of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. While in mainstream Christianity God is thought of in masculine terms, teachings generally state that God has no gender, except in his incarnation as Jesus Christ, due to the fact that He is a spiritual being. However, the names of Father and Son clearly imply masculinity, and the Gospel of John implies the masculinity of the Spirit by applying a masculine demonstrative pronoun to the grammatically neuter antecedent. Still, teachings regarding the gender and nature of God vary between Christian groups, and some clearly state that God is male. These include the teachings of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which explicitly describe God the Father as being male, corporeal, and separate in being from the Son, Jesus Christ. Unusually, Latter-day Saint teachings also indicate the existence of a Heavenly Mother, who is the wife of the Heavenly Father, and that together they are the spiritual parents of humankind. This reinforces the idea that God is analogous to our earthly fathers. However, these beliefs are not common among Christian groups, which generally see God as having both male and female attributes and therefore no need for a female counterpart.

In many polytheistic religions, there are both gods and goddesses clearly defined. This includes many pagan religions, such as those involving Greek mythology, Norse mythology, and Celtic mythology. This distinction also exists in other polytheisms. For example, Hinduism distinguishes between God and Goddess. There are three main male gods known as Tridev (Sanskrit:त्रिदेव) and their wives are worshiped as goddesses. In Hindu mythology, all the forces converge to form a female supreme power known as aadishakti (Sanskrit: आदिशक्ति.).

Religious organization

All three Abrahamic religions were founded by men, so some scholars and psychologists have theorized that they may dramatize important themes around men's relationship with their fathers for the western world.[5][6] Conversely, conservative theologians within these traditions, especially Christianity, see fatherhood itself modeled on God the Father.

In his book Moses and Monotheism, Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, presents his thesis that Judaism is the religion of the father and Christianity is the religion of the son.

Literature

The study of masculine psychology has brought about the publication of several books.

Eugene Monick

In his books Phallos: Sacred Image of the Masculine and Castration and Male Rage, Monick correlates male sexuality and spirituality, arguing that the "phallos" (erect penis) is something of an existential God-image for men. He also presents his thesis that there is a difference between masculinity and patriarchy. The author also argues that there is a deep need within men to participate in a fraternity with men and to have their maleness recognized by other men, but that our society often does not take this into account. The author claims that what usually results is that these needs become frustrated and manifest themselves in often anti-social behavior and activities, such as hazing rituals.

The author says it is puzzling that we live in what he considers a male-dominated society, and yet very little work has been done to understand the archetypal basis of masculinity. He suggests that this may be due to a societal assumption of male superiority, founded on the belief that one should not question that which is deemed to be right and superior.

Susan Faludi

Susan Faludi, a noted feminist author, published Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man in 1999. In this book she claims that in the 20th century men suffered from the breakdown of patriarchal structures.

David Deida

David Deida, a noted author and spiritual practitioner, published The Way Of The Superior Man: A Spiritual Guide to Mastering the Challenges of Woman, Work, and Sexual Desire in 1997. In this book he argues "It is time to evolve beyond the (first-stage) macho jerk ideal, all spine and no heart. It is also time to evolve beyond the (second-stage) sensitive and caring wimp ideal, all heart and no spine. Heart and spine must be united in a single man, and then gone beyond in the fullest expression of love and consciousness possible, which requires a deep relaxation into the infinite openness of this present moment. And this takes a new kind of (third-stage) guts. This is the way of the superior man."[7]

Robert Bly

Robert Bly inspired the mythopoetic men's movement with his 1990 book Iron John: A Book About Men[8] consisting of retellings of archetypal male myths and analysis of the Grimms' Fairy Tale "Iron John".

Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette

Robert L. Moore and Douglas Gillette collaborated on a series of five books on male psychology and mythopoetic aspects of human development, including King, Warrior, Magician, Lover, and a book exploring each of these four archetypes. The book and its authors are considered important parts of the men's movement in the latter part of the 20th century.

The male fear of the feminine

The male fear of the feminine is a phenomenon that has been discussed since the 1930s. It was first introduced by the German psychoanalyst and critic of Freudian theory, Karen Horney (1932) in her paper titled "The Dread of Woman." Erich Neumann (1954), a German-born Jungian analyst, dedicated one essay to the discussion, titled "The fear of the feminine" (Orig: Die Angst vor dem Weiblichen, 1959). Neumann regards "patriarchal normality as a form of fear of the feminine" (p. 261).

A later contributor is Chris Blazina, a psychodynamic psychologist and professor based at Tennessee State University. Blazina considers that "the fear of the feminine helps define what is masculine" (1997). In 1986, James O'Neil et al. theorized that the male fear of the feminine is a core aspect of the male psyche. He developed a 37-question psychometric test, a gender role conflict scale (GRCS), to measure the extent to which a man is in conflict with traditional masculine role values. This test is built upon the notion of the male fear of the feminine.[9]

In 2003, Werner Kierski, a London-based German-born psychotherapist and researcher, associated with humanistic psychology and transpersonal and existential psychotherapy designed the first empirical research into the male fear of the feminine with the results published in 2007 and presented to the public at the 2007 annual conference of the American Men's Studies Association (AMSA) and at the 2007 research conference of the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP).

According to the various sources, the male fear of the feminine is connected to influences from their mothers and to cultural norms that prescribe how men must behave in order to feel accepted as men.

When men experience vulnerable feelings and other feelings that are associated with women, men can become frightened. According to Kierski (2007), the fear of the feminine then acts in two ways: a) Like an internal monitor to ensure that men stay within the boundaries of what is regarded as masculine, i.e. being action orientated, self-reliant, guarded, and seemingly independent; b) if a man fails to experience this and feels out of control, vulnerable or dependent, the fear of the feminine can act like a defence, leading to splitting off, repressing, or projecting those feelings.

Figure 1: Male fear of the feminine as an internal monitor and as a defense. Source: Werner Kierski.

Male fear of the feminine as an internal monitor.

Male fear of the feminine as an internal monitor. Male fear of the feminine as a psychological defense.

Male fear of the feminine as a psychological defense.

Kierski's research claimed that men do acknowledge that male fear of the feminine can have a strong influence on both hetero- and homosexual men. The research has also indicated that there appears to be a link between fear of the feminine and men's negative views about counseling and psychotherapy. In addition, this research has identified four possible groups of experiences that lead to male fear of the feminine, which relate to internal and external triggers. These are: Experiencing vulnerability and uncertainty; women who are strong and competent; women who are angry or aggressive; women who are like their mothers.

Homophobia

Issues of homophobia and gay bashing are of relevance to the study of masculine psychology. Every year, men (such as Matthew Shepard) die as a result of gay bashing.[10] The victims of gay bashing attacks are most often homosexual males, or those who display what are commonly perceived as effeminate behaviors or mannerisms which are, when seen in males, often associated with homosexuality. Self-identified heterosexual males are usually the perpetrators of gay bashing attacks.[11][12]

Sigmund Freud presented the thesis that everyone is at some level bisexual,[13] and Alfred Kinsey research results claimed that as many as 37% of American males had engaged in homosexual activity.[14] French-Canadian psychologist Guy Corneau says that despite Kinsey's research results, attitudes toward homosexuality have remained hostile.[15]

Historical perspectives

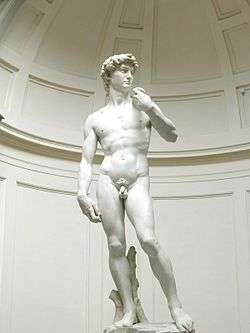

Among artists and scientists during the Renaissance, it was the prevailing belief that the study of the male form was in itself a study of God. Michelangelo's David is based upon this artistic discipline, which is known as disegno. Under this discipline, sculpture is considered to be the finest form of art because it mimics divine creation. Because Michelangelo adhered to the concepts of disegno, he worked under the premise that the image of David was already in the block of stone he was working on—in much the same way as the human soul is thought by some to be found within the physical body.

Sports

Competitive sports are heavily influenced by masculine psychology. Though females do play sports, culturally male athletes are often accorded more attention and respect than their female counterparts. The Modern Olympics are based on the Ancient Olympic Games of Greece. In the ancient Grecian games, not only were women forbidden from competing in the games, they were not even allowed to attend the Olympic games. Sports terminology has been transmuted into common day slang, often with sexual connotation. For example, it is common for males to refer to "scoring" with a woman.

See also

References

- ↑ Kendall, Diane (2011). Sociology in Our Times: The Essentials. Cengage Learning. p. 315. ISBN 1-111-30550-1.

- ↑ Absent Fathers, Lost Sons listing (ISBN 0-87773-603-0)

- ↑ Tacey, D. "Remaking men. Jungian thought and the post patriarchal psyche". Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ↑ God and gender: "

- ↑ Levenson, J. "The idea of abrahamic religions: A qualified dissent". Jewish Review of Books. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ↑ Neal, R. (2011). "Engaging abrahamic masculinity: Race, religion, and the measure of manhood.". Association for religion and intellectual life. 61: 557–564. doi:10.1111/j.1939-3881.2011.00204.x.

- ↑ Deida, David; The Way of the Superior Man, 1997, p. 10.

- ↑ Robert Bly: Iron John: A Book About Men (1990) ISBN 0-201-51720-5

- ↑ Jim O'Neil, University of Connecticut

- ↑ Gay Bashing Retrieved June 5, 2006

- ↑ Bureau of Justice Statistics Retrieved June 9, 2006

- ↑ Homicide trends in the U.S. Trends by gender Retrieved June 9, 2006

- ↑ Storr, Anthony. Freud: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, USA; New edition (April 9, 2001) (ISBN 0-19-285455-0) Page 152: "Freud asserted that everyone is bisexual at some level."

- ↑ Kinsey, Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male p. 656

- ↑ Guy Corneau. Absent Fathers, Lost Sons: The Search for Masculine Identity (ISBN 0-87773-603-0). Page 65. "It is depressing to realize that more than forty years after the publication of the Kinsey Report, attitudes toward homosexuality have remained so hostile, despite (or could it be because), as Kinsey's research showed, 37 percent of the American male population has engaged in homosexual behavior to ejaculation after the age of puberty?"

Bibliography

- Blazina, C. 1997. The Fear of the Feminine in the Western Psyche and the Masculine Task of Dissidentification. The Journal of Men's Studies Vol 9, no 22.

- Blazina, C. (2003). The Cultural Myth of Masculinity. Westport, CT: Praeger. (ISBN 0-275-97990-3)

- Horney, K. (1932). The dread of woman. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 13, republished in Grigg, R., Hecq, D., and Smith, C., (Eds) (1999). Female Sexuality: The Early Psychoanalytic Controversies. London: Rebus Press. (ISBN 1-892746-39-5)

- Kierski, W. 2002. Female violence: can we therapists face up to it? Counselling and Psychotherapy Journal, Vol 13, no 10, December 2002, pp. 32–35. (ISSN 1474-5372)

- Kierski, W. 2007. Men and the Fear of the Feminine. Self & Society. Vol 34, no 5. March–April 2007, p. 27–33.

- Neumann, E. 1994. The Fear of the Feminine. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (ISBN 0-691-03473-7) (First published in German as: die Angst vor dem Weiblichen, 1959. Zürich: Racher Verlag)

- O'Neil, J.M., Helmes, B.J., Gable, R.K., David, L., Wrightsman, L.S. 1986. Gender-Role-Conflict-Scale: College men's fear of the feminine. Sex Roles. No. 14, p. 335–350.

External links

- "Books on Masculine Psychology": Inner City Books (Studied in Jungian Psychology by Jungian Analysts)

- Masculine Psychology by Roya Monajem

- He: Understanding Masculine Psychology

- The Jung Page: Feminine and Masculine Psychology

- Books & Audio on Masculine Psychology By: Dr. Robert Moore

- A response paper by Harvey Hall, regarding Eugene Monick's "Phallos: Sacred Image of the Masculine"