Mashallah ibn Athari

| Masha'allah ibn Athari | |

|---|---|

| Born |

740 Basra, Abbasid Caliphate, Iraq |

| Died |

815 (aged 75) Baghdad, Abbasid Caliphate, Iraq |

| Occupation | Astronomer |

Masha'Allah ibn Atharī (c.740–815 CE) was an eighth-century Persian Jewish[1] astrologer and astronomer from the city of Basra (located in Iraq) who became the leading astrologer of the late 8th century.[2] According to Ibn al-Nadim in his Fihrist, Mashallah was "a man of distinction and during his period the leading person for the science of judgments of the stars".[3] He served as a court astrologer for the Abbasid caliphate, and wrote a number of works on astrology in Arabic, some of which have only survived in Latin translations. Science historian Donald Hill writes that Mashallah was originally from Khorasan.[4]

The Arabic phrase ma sha`a allah indicates acceptance of what God has ordained in terms of good or ill fortune that may befall a believer. Ibn al-Nadim said Mashallah's name was Mīshā, meaning Yithro (Jethro).[5] Latin translators also called him Messahala (with many variants, such as Messahalla, Messala, Macellama, Macelarma, Messahalah).

The crater Messala on the Moon is named after him.

Life and works

| Astrology |

|---|

New millennium astrological chart |

| Background |

| Traditions |

| Branches |

|

|

As a young man he participated in the founding of Baghdad for Caliph Al-Mansur in 762 by working with a group of astrologers led by Naubakht the Persian to pick an electional horoscope for the founding of the city.[6] He wrote over twenty works on predominantly astrology, which became authoritative in later centuries at first in the Middle East, and then in the West when horoscopic astrology was transmitted back to Europe beginning in the 12th century. His writings include both what would be recognized as traditional horary astrology and an earlier type of astrology which casts consultation charts to divine the client's intention.[6] It is also known that his work was heavily influenced by Hermes Trismegistus and Dorotheus.[7] Only one of his writings is still extant in its original Arabic,[8] but there are many medieval Latin,[9] Byzantine Greek[10][11] and Hebrew translations. His treatise De mercibus (On Prices) is the oldest extant scientific work in Arabic.[12]

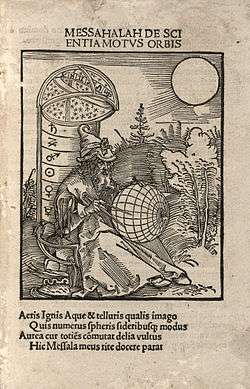

One of his most popular works in the Middle Ages was a cosmological treatise which provides a comprehensive account of the whole cosmos along Aristotelian lines. In it, Mashallah covers many topics that were important in early cosmology and strays away from traditional cosmology by postulating a ten-orb universe. Mashallah had intended for his account to be aimed at laymen and therefore included diagrams with text to facilitate comprehension of his main ideas. The treatise was printed in two manuscript versions: a short version of 27 chapters known as De scientia motus orbis and an expanded version of 40 chapters known as De elementis et orbibus.[3] The shorter version was translated by Gherardo Cremonese (Gerard of Cremona). Both were printed in Nuremberg and in 1504 and 1549, respectively. This work is commonly referred to as De orbe for short.

Mashallah wrote the first treatise on the astrolabe (p 10) in Arabic.[7] It was later translated into Latin as De Astrolabii Compositione et Ultilitate and included in Gregor Reisch's Margarita phylosophica (ed. pr., Freiburg, 1503; Suter says the text is included in the Basel edition of 1583). Its contents primarily deal with the construction and usage of an astrolabe.

His On Conjunctions, Religions, and People discusses the astrology of important world events and the role Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions have in their timing. This treatise does not survive intact and is preserved only in quotations by the Christian astrologer Ibn Hibinta.[13] Other notable works are his Liber Messahallaede revoltione liber annorum mundi, a work on revolutions, and De rebus eclipsium et de conjunctionibus planetarum in revolutionibus annorm mundi, a work on eclipses. His work on nativities, with the Arabic title Kitab al - Mawalid, has been partially translated into English from a Latin translation of the Arabic by James H. Holden.[7] Other astronomical and astrological writings are quoted by Suter and Steinschneider. An Irish astronomical tract also exists based in part on a medieval Latin version. Edited with preface, translation, and glossary, by Afaula Power (Irish Texts Society, vol. 14, 194 p., 1914). The notable 12th-century scholar and astrologer Abraham ibn Ezra translated two of Mashallah's astrological treatises into Hebrew: She'elot and Ḳadrut (Steinschneider, "Hebr. Uebers." pp. 600–603). Eleven of Mashallah's astrological treatises were translated out of Latin into English in 2008 and are available in The Works of Sahl and Masha'allah by Benjamin N. Dykes. On Reception is also available in an English translation by Robert Hand[14] from the Latin edition by Joachim Heller of Nuremberg in 1549.

Philosophy

Mashallah postulated a ten-orb universe rather than the eight-orb model offered by Aristotle and the nine-orb model that was popular in his time. In all Mashallah's planetary model ascibres the universe 26 orbs, which account for the relative positioning and motion of the seven planets. Of the ten orbs, the first seven contain the planets and the eighth contain the fixed stars. The ninth and tenth orbs were named by Mashallah the "Orb of Signs" and the "Great Orb", respectively. Both of these orbs are starless and move with the diurnal motion, but the tenth orb moves in the plane of the celestial equator while the ninth orb moves around poles that are inclined 24° with respect to the poles of the tenth orb. The ninth is also divided into twelve parts which are named after the zodiacal constellations that can be seen beneath them in the eighth orb. The eight and ninth orbs move around the same poles, but with different motion. The ninth orb moves with daily motion, so that the 12 signs are static with respect to the equinoxes, the eighth Orb of the Fixed Stars moves 1° in 100 years, so that the 12 zodiacal constellations are mobile with respect to the equinoxes.[3] The eight and ninth orbs moving around the same poles also guarantees that the 12 stationary signs and the 12 mobile zodiacal constellations overlap. By describing the universe in such a manner, Mashallah was attempting to demonstrate the natural reality of the 12 signs by stressing that the stars are located with respect to the signs and that fundamental natural phenomena, such as the beginning of the seasons, changes of weather, and the passage of the months, take place in the sublunar domain when the sun enters the signs of the ninth orb .[3]

Mashallah was an advocate of the idea that the conjunctions of Saturn and Jupiter dictate the timing of important events on Earth. These conjunctions, which occur about every twenty years, take place in the same triplicity for about two hundred years, and special significance is attached to a shift to another triplicity.[13]

Bibliography

- De cogitatione

- Epistola de rebus eclipsium et conjunctionibus planetarum (distinct from De magnis conjunctionibus by Abu Ma'shar al Balkhi ; Latin translation : John of Sevilla Hispalenis et Limiensis

- De revolutionibus annorum mundi

- De significationibus planetarum in nativitate

- Liber receptioni

- Works of Sahl and Masha'allah, trans. Benjamin Dykes, Cazimi Press, Golden Valley, MN, 2008.

- Masha'Allah, On Reception, trans. Robert Hand, ARHAT Publications, Reston, VA, 1998.

See also

- Liber de orbe

- Astrology in medieval Islam

- Jewish views of astrology

- List of Persian scientists and scholars

Notes

- ↑ Islam and Science, by M. H. Syed, p. 212

- ↑ David Pingree: "Māshā'allāh", Dictionary of Scientific Biography 9 (1974), 159–162.

- 1 2 3 4 Sela, Shlomo (2012). "Maimonides and Mashallah on the Ninth Orb of the Signs and Astrology". Historical Studies in Science and Judaism. Indiana University: Aleph. 12 (1): 101–134. doi:10.2979/aleph.12.1.101. Retrieved 3 Nov 2013.

- ↑ Donald R. Hill. Islamic Science and Engineering, 1994. p10. ISBN 0-7486-0457-X

- ↑ Belenkiy, Ari (2007). "Māshāʾallāh ibn Atharī (Sāriya)". In Thomas Hockey; et al. The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 740–1. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0..

- 1 2 Benjamin N. Dykes [translator]. Works of Sahl and Masha'allah. Cazimi Press, 2008. .

- 1 2 3 "The Encyclopedia of Heavenly Influences". The Astrology Book. Visible Ink Press. 2003. pp. 430–431. .

- ↑ David Pingree: "Māshā'allāh: Greek, Pahlavī, Arabic, and Latin Astrology", in Perspectives arabes et médiévales sur la tradition scientifique et philosophique grecque. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 79. Leuven-Paris 1997. 123–136.

- ↑ Lynn Thorndike: "The Latin Translations of Astrological Works by Messahala", Osiris 12 (1956), 49–72.

- ↑ David Pingree: "The Byzantine Translations of Māshā'allāh on Interrogational Astrology", in The Occult Sciences in Byzantium. Ed. Paul Magdalino, Maria V. Mavroudi. Geneva 2006. 231–243.

- ↑ David Pingree: "From Alexandria to Baghdād to Byzantium: The Transmission of Astrology", International Journal of the Classical Tradition, Summer 2001, 3–37.

- ↑ Durant, Will (1950). The Age of Faith: A History of Medieval Civilization – Christian, Islamic, and Judaic – from Constantine to Dante A.D. 325–1300, p. 403. New York: Simon and Schuster

- 1 2 Lorch, R.P. (September 2013). "The Astrological History of Māshā'allāh". The British Journal for the History of Science. Cambridge, Mass: Cambridge University Press. 6 (4): 438–439. doi:10.1017/s0007087400012644. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ Robert Hand [translator]. On Reception by Masha'allah. ARHAT (Archive for the Retrieval of Historical Astrological Texts), 1998.

References

- Jewish Encyclopedia – Mashallah

- James Holden, A History of Horoscopic Astrology, American Federation of Astrologers, Tempe, AZ, 1996. ISBN 0-86690-463-8 Pgs. 104–107

- "An Irish Astronomical Tract" translates by unknown, Two-thirds of the tract are part paraphrase and part translation of a Latin version of an Arabic treatise by Messahalah. University College of Cork in Ireland (Coláiste na hOllscoile Corcaigh) An Irish Astronomical Tract

External links

- Belenkiy, Ari (2007). "Māshāʾallāh ibn Atharī (Sāriya)". In Thomas Hockey; et al. The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 740–1. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version)

- Blog, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries Pseudo-Masha’Allah, On the Astrolabe, ed. Ron B. Thomson, version 1.0 (Toronto, 2012); A Critical Edition of the Latin Text with English Translation by Ron B. Thomson.