Black catbird

| Black catbird | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Mimidae |

| Genus: | Melanoptila P.L. Sclater, 1858 |

| Species: | M. glabrirostris |

| Binomial name | |

| Melanoptila glabrirostris PL Sclater, 1858 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Turdus glabrirostris Gray, 1869[2] | |

The black catbird (Melanoptila glabrirostris) is a songbird species in the monotypic genus Melanoptila, part of the family Mimidae. At 19–20.5 cm (7.5–8 in) in length and 31.6–42 g (1.1–1.5 oz) in mass, it is the smallest of the mimids. Sexes appear similar, with glossy black plumage, black legs and bill, and dark reddish eyes. The species is endemic to the Yucatán Peninsula, and is found as far south as Campeche, northern Guatemala and northern Belize. Although there are historical records from Honduras and the US state of Texas, the species is not now known to occur in either location. It is found at low elevations in semi-arid to humid habitats ranging from shrubland and abandoned farmland to woodland with thick understory, and is primarily sedentary.

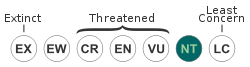

Although it is a mimid, the black catbird is not known to imitate any other species. Its song is a mix of harsh notes and clear flute-like whistles, with the phrases repeated. It builds a cup nest in low bushes or trees, and lays two bluish eggs. It is threatened by habitat loss, and has been assessed as near threatened by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Systematics

When Philip Sclater first described the black catbird in 1858, from a specimen collected in Omoa Honduras, he assigned it to the monotypic genus Melanoptila, which he created at the same time.[3] At least one subsequent ornithologist assigned the species to the genus Turdus, believing it to be a thrush, but most agreed with Sclater's assessment.[3] DNA studies have since shown that it is most closely related to various endemic Antillean mimids and the gray catbird,[4] and it is sometimes included with the latter species in the genus Dumetella.[5] Although some taxonomists place the birds from Mexico's Cozumel Island in a separate subspecies (M. g. cozumelana), most authorities do not feel that such distinction is warranted and the species is generally regarded as monotypic throughout its range.[5]

The genus name Melanoptila is a compound word created from two Greek words: melas, meaning "black" and ptilon, meaning "plumage".[6] This and the "black" of the bird's common name are a straightforward reference to its general appearance. The species name glabrirostris is a combination of two Latin words: glaber, meaning "smooth or hairless" and rostris, meaning "beak" (rostrum).[7] This is a reference to the very small rictal bristles which surround the black catbird's beak, in marked comparison to the prominent bristles found on the gray catbird.[8]

Description

.jpg)

At 19–20.5 cm (7.5–8 in) in length and 31.6–42 g (1.1–1.5 oz) in mass, the black catbird is the smallest of the mimids.[5][nb 1] It has short, rounded wings and a relatively long tail. The sexes are similar in appearance, though the male tends to be heavier.[5] The plumage is glossy black with a purplish sheen overall, though the rectrices and primary and secondary coverts have a greenish sheen and the remiges are a duller blackish-brown color showing reduced sheen. The female is less glossy than the male,[8] and juveniles are brownish-gray with mottling below.[5] The legs are black. The bill, which is black and shorter than the head, has a generally straight culmen, decurved toward the tip.[8] The iris is a dark reddish color in adults and gray in juveniles.[5]

Similar species

Although the black catbird is unlikely to be mistaken for any other mimid species, there are several other black birds — including the melodious blackbird, the bronzed cowbird and the giant cowbird — that occur within the same range and might conceivably cause confusion.[8] All are birds of more open habitats. The melodious blackbird is larger and longer tailed; it has dark eyes and a stocky bill with an evenly curved culmen.[10] The bronzed cowbird is thicker necked than is the catbird and has a bronzy, rather than purplish or greenish gloss to its plumage; its eye is bright red rather than dark red.[11] The giant cowbird is considerably larger, and is relatively longer tailed and thicker necked than is the catbird.[12]

Range and habitat

The black catbird is endemic to the Yucatán Peninsula. It occurs as far south as the Mexican state of Campeche, northern Guatemala and northern Belize,[5] and is found on the offshore islands of Cozumel, Isla Mujeres, Ambergris Caye, Caye Caulker, Lighthouse Reef and Glover's Reef.[8] Although the type specimen of the bird was apparently collected in northwestern Honduras in 1855 or 1856, it has not been recorded in that country since, and must have been rare if it was ever there.[5] Some authors feel that the specimen might have been mislabeled, and have come instead from northwestern "British Honduras" as Belize was then called.[8] There is also a single specimen of a black catbird collected from Brownsville, Texas in 1892.[13] Although obtained by a reportedly reputable collector, and accepted by the Texas State Records Committee, the origin of this specimen is a source of some controversy, and it has not been accepted by the American Birding Association or the American Ornithologists' Union.[14]

The species is found at low elevations in semi-arid to humid areas in habitats ranging from scrubland and abandoned farmland to wood edge.[5][8] It prefers areas with dense thickets, scrub or understory, and is uncommon in taller forest where the vegetation beneath the canopy is more open.[5] Although it is largely sedentary, there may be some localized seasonal movements away from the drier northern parts of the Yucatán Peninsula in late summer to early winter.[5]

Behavior

.jpg)

Voice

Unlike many of its fellow mimids, the black catbird is not known to imitate any other species. Its song consists of repeated phrases of notes ranging from harsh and scratchy to warbled and flute-like,[5] often interspersed with metallic clicking buzzes.[8] It often sings from exposed perches.[8] It has a variety of calls, including some which are quite similar to those of the gray catbird;[8] these are variously described as a harsh rriah, a nasal chrrh and a grating tcheeu.[5]

Food and feeding

Although no specific studies have been done on the black catbird's feeding ecology, it is thought to be an omnivore, like its close relatives are.[8] It is known to eat the fruits of Bursera simaruba and Ficus cotinifolia, two deciduous trees found in the Neotropics.[15]

Breeding

Little is known about the breeding biology of the black catbird. Its breeding season appears to run from spring through summer; nest building was observed in Belize in early May, and small young were found in a nest in Mexico in mid-August.[5] The nest, an open cup of twigs lined with rootlets and other fine material, is placed low in a dense bush or small tree.[5][8] The female lays two greenish-blue eggs.[5] However, details of nest-building, incubation times, parental care, fledging periods and number of broods are unknown.[8]

Conservation and threats

The range of the black catbird is small and dwindling further due to habitat loss. In 2008, the world population was estimated to be less than 50,000 and decreasing. Due to the speed of its decline, which is reported to have been "precipitous" on Caye Caulker between 2003 and 2008, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature has assessed the species as near threatened.[1] The late 20th century arrival of the shiny cowbird, a brood parasite, into the Yucatán may cause problems for the black catbird as (based on past host choices) the catbird may become a target of the cowbird.[16]

Note

- ↑ By convention, length is measured from the tip of the bill to the tip of the tail on a dead bird (or skin) laid on its back.[9]

References

- 1 2 BirdLife International (2012). "Melanoptila glabrirostris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Ridgway & Friedmann (1901), p. 215.

- 1 2 Ridgway & Friedmann (1901), p. 214.

- ↑ Hunt, Jeffrey S.; Bermingham, Eldridge; Ricklefs, Robert E. "Molecular systematics and biogeology of Antillean thrashers, tremblers and mockingbirds (Aves: Mimidae)" (PDF). The Auk. 118 (1): 35–55. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2001)118[0035:MSABOA]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4089757. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Cody (2005), p. 479.

- ↑ Jobling (2010), p. 248.

- ↑ Jobling (2010), p. 173.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Brewer, David (2010). Wrens, Dippers and Thrashers. London, UK: Christopher Helm. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-8734-0395-2.

- ↑ Cramp, Stanley, ed. (1977). Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa: Birds of the Western Palearctic, Volume 1, Ostrich to Ducks. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-857358-6.

- ↑ Jaramillo & Burke (1999), p. 329.

- ↑ Jaramillo & Burke (1999), p. 375.

- ↑ Jaramillo & Burke (1999), p. 371.

- ↑ Lockwood, Mark; Freedom, Brush (2004). The TOS Handbook of Texas Birds. College Station, TX, US: Texas A & M University Press. p. 162. ISBN 1-58544-284-4.

- ↑ Dunn, Jon (2004). "Review: The TOS Handbook of Texas Birds". Wilson Bulletin. 116 (4): 366–367. doi:10.1676/0043-5643(2004)116[0366:TTHOTB]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4164705 – via JSTOR. (registration required (help)).

- ↑ Scott, Peter E.; Martin, Robert F. (December 1984). "Avian Consumers of Bursera, Ficus, and Ehretia Fruit in Yucatan". Biotropica. 16 (4): 319–323. doi:10.2307/2387943. JSTOR 2387943 – via JSTOR. (registration required (help)).

- ↑ Kluza, Daniel A. (September 1998). "First Record of Shiny Cowbird (Molothrus bonariensis) in Yucatán, Mexico" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 110 (3): 429–430. JSTOR 4163974. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

Cited texts

- Cody, M. L. (2005). "Family Mimidae (Mockingbirds and Thrashers)". In del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Christie, David. Handbook of Birds of the World: Cuckoo-shrikes to Thrushes. 10. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions. pp. 448–495. ISBN 84-87334-72-5.

- Jaramillo, Alvaro; Burke, Peter (1999). New World Blackbirds. London, UK: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-4333-1.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Names. London, UK: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Ridgway, Robert; Friedmann, Herbert (1901). The Birds of North and Middle America. Washington, D.C.: Government Publishing Office.

External links

- Black catbird photos on the Academy of Natural Sciences' Visual Resources for Ornithology website

- Black catbird photos and videos on the Internet Bird Collection website

- Black catbird vocalizations on the Macauley Library's (Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology) website

- Black catbird vocalizations on the xeno-canto.org website