Merino

The Merino is an economically influential breed of sheep prized for its wool. The breed origins are from Spain, but the modern Merino was domesticated in Australia. Today, Merinos are still regarded as having some of the finest and softest wool of any sheep. Poll Merinos have no horns (or very small stubs, known as scurs), and horned Merino rams have long, spiral horns which grow close to the head.[1]

Etymology

Two suggested origins for the Spanish word merino are:[2]

- It may be an adaptation to the sheep of the name of a Leonese official inspector (merino) over a merindad, who may have also inspected sheep pastures. This word is from the medieval Latin maiorinus, a steward or head official of a village, from maior, meaning "greater".

- It also may be from the name of an Imazighen tribe, the Marini (or in Castilian, Benimerines), who intervened in the Iberian peninsula during the 12th and 13th centuries.

Characteristics

The Merino is an excellent forager and very adaptable. It is bred predominantly for its wool,[3] and its carcass size is generally smaller than that of sheep bred for meat. South African Meat Merino (SAMM), American Rambouillet and German Merinofleischschaf[4] have been bred to balance wool production and carcass quality.

Merino need to be shorn at least once a year because their wool does not stop growing. If the coat is allowed to grow, it can cause heat stress, mobility issues, and blindness.[5]

Wool qualities

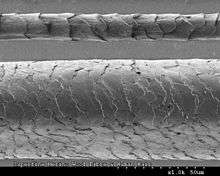

Merino wool is finely crimped and soft. Staples are commonly 65–100 mm (2.6–3.9 in) long. A Saxon Merino produces 3–6 kg (6.6–13.2 lb) of greasy wool a year, while a good quality Peppin Merino ram produces up to 18 kg (40 lb). Merino wool is generally less than 24 micron (µm) in diameter. Basic Merino types include: strong (broad) wool (23–24.5 µm), medium wool (19.6–22.9 µm), fine (18.6–19.5 µm), superfine (15–18.5 µm) and ultra fine (11.5–15 µm).[6] Ultra fine wool is suitable for blending with other fibers such as silk and cashmere. New Zealand produces lightweight knits made from Merino wool and possum fur.[7]

The term merino is widely used in the textile industries, but it cannot be taken to mean the fabric in question is actually 100% merino wool from a Merino strain bred specifically for its wool. The wool of any Merino sheep, whether reared in Spain or elsewhere, is "merino wool". However, not all merino sheep produce wool suitable for clothing, and especially for clothing worn next to the skin. This depends on the particular strain of the breed. Merino sheep bred for meat do not produce a fleece with a fine enough staple for this purpose.

Athletic clothing and outdoor accessories

Merino wool is common in high-end, performance athletic wear and gear. Typically meant for use in running, hiking, skiing, mountain climbing, cycling, hunting and in other types of outdoor aerobic exercise, these clothes and accessories command a premium over synthetic fabrics.

Several properties contribute to merino's popularity for exercise clothing, compared to wool in general and to other types of fabric:

- Merino is excellent at regulating body temperature, especially when worn against the skin. The wool provides some warmth, without overheating the wearer. It draws moisture (sweat) away from the skin, a phenomenon known as wicking, which results in helping the wearer stay comfortable whether it be in warm or cold conditions. The fabric is slightly moisture repellent (keratin fibers are hydrophobic at one end and hydrophilic at the other), allowing the user to avoid the feeling of wetness.[8]

- Like cotton, wool absorbs water (up to 1/3 its weight), but, unlike cotton, wool retains warmth when wet,[9] thus helping wearers avoid hypothermia after sweating from strenuous exercise or getting rained on when outside.[8]

- Like most wools, merino contains lanolin, which has antibacterial properties, resulting in reduced human body odor. It is not uncommon for users to wear a garment for multiple days in a row.[10]

- Merino is one of the softest types of wool available, because of finer fibers and smaller scales.[9]

- Merino has an excellent warmth-to-weight ratio compared to other wools, in part because the smaller fibers have microscopic cortices of dead air, trapping body heat similarly to the way a sleeping bag warms its occupant.[11]

- Unlike synthetic fibers, Merino wool is a responsive natural material that adapts to your body’s temperature to regulate insulation and breathability. This means it keeps you cool when you’re hot and warms you up when you’re cold thanks to millions of tiny air pockets within the fibers.[12]

History

The Phoenicians introduced sheep from Asia Minor into North Africa and the foundation flocks of the merino in Spain might have been introduced as late as the 12th century by the Marinids, a tribe of Berbers. although there were reports of the breed in the Iberian peninsula before the arrival of the Marinids; perhaps these came from the Merinos or tax collectors of the Kingdom of León, who charged the tenth in wool, beef jerky and cheese. In the 13th and 14th centuries, Spanish breeders introduced English breeds which they bred with local breeds to develop the merino; this influence was openly documented by Spanish writers at the time.[13]

Spain became noted for its fine wool (spinning count between 60s and 64s) and built up a fine wool monopoly between the 12th and 16th centuries, with wool commerce to Flanders and England being a source of income for Castile in the Late Middle Ages.

Most of the flocks were owned by nobility or the church; the sheep grazed the Spanish southern plains in winter and the northern highlands in summer. The Mesta was an organisation of privileged sheep owners who developed the breed and controlled the migrations along cañadas reales suitable for grazing.

The three Merino strains that founded most of the world's Merino flocks were the Royal Escurial flocks, the Negretti and the Paula. The Infantado, Montarcos and Aguires studs had an influence on the Vermont bloodlines.

Before the 18th century, the export of Merinos from Spain was a crime punishable by death. In the 18th century, small exportation of Merinos from Spain and local sheep were used as the foundation of Merino flocks in other countries. In 1723, some were exported to Sweden, but the first major consignment of Escurials was sent by Charles III of Spain to his cousin, Prince Xavier the Elector of Saxony, in 1765. Further exportation of Escurials to Saxony occurred in 1774, to Hungary in 1775 and to Prussia in 1786. Later in 1786, Louis XVI of France received 366 sheep selected from 10 different cañadas; these founded the stud at the Royal Farm at Rambouillet. The Rambouillet stud enjoyed some undisclosed genetic development with some English long-wool genes contributing to the size and wool-type of the French sheep.[14] Through Emperor, the Rambouillet stud had an enormous influence on the development of the Australian Merino.

Sir Joseph Banks procured two rams and four ewes in 1787 by way of Portugal, and in 1792 purchased 40 Negrettis for King George III to found the royal flock at Kew. In 1808, 2000 Paulas were imported.

The King of Spain also gave some Escurials to the Dutch government in 1790; these thrived in the Dutch Cape Colony (South Africa). Two years earlier in 1788 John MacArthur, from the Clan Arthur (or MacArthur Clan) introduced Merinos to Australia from South Africa.

From 1765, the Germans in Saxony crossed the Spanish Merino with the Saxon sheep[15] to develop a dense, fine type of Merino (spinning count between 70s and 80s) adapted to its new environment. From 1778, the Saxon breeding center was operated in the Vorwerk Rennersdorf. It was administered from 1796 by Johann Gottfried Nake, who developed scientific crossing methods to further improve the Saxon Merino. By 1802, the region had four million Saxon Merino sheep, and was becoming the centre for stud Merino breeding, and German wool was considered to be the finest in the world.

In 1802, Colonel David Humphreys, United States Ambassador to Spain, introduced the Vermont strain into North America with an importation of 21 rams and 70 ewes from Portugal and a further importation of 100 Infantado Merinos in 1808. The British embargo on wool and wool clothing exports to the U.S. before the 1812 British/U.S. war led to a "Merino Craze", with William Jarvis of the Diplomatic Corps importing at least 3,500[16] sheep between 1809 and 1811 through Portugal.

The Napoleonic wars (1793–1813) almost destroyed the Spanish Merino industry. The old cabañas were dispersed or slaughtered. From 1810 onwards, the Merino scene shifted to Germany, the United States and Australia. Saxony lifted the export ban on living Merinos after the Napoleonic wars. Highly decorated Saxon sheep breeder Nake from Rennersdorf had established a private sheep farm in Kleindrebnitz in 1811, but ironically after the success of his sheep export to Australia and Russia, failed with his own undertaking.

United States Merinos

Vermont

Merino sheep were introduced to Vermont in 1802. This ultimately resulted in a boom-bust cycle for wool, which reached a price of 57 cents/pound in 1835. By 1837, 1,000,000 sheep were in the state. The price of wool dropped to 25 cents/pound in the late 1840s. The state could not withstand more efficient competition from the Western states, and sheep-raising in Vermont collapsed.[17]

Australian Merinos

Early history

About 70 native sheep, suitable only for mutton, survived the journey to Australia with the First Fleet, which arrived in late January 1788. A few months later, the flock had dwindled to just 28 ewes and one lamb.[18]

In 1797, Governor King, Colonel Patterson, Captain Waterhouse and Kent purchased sheep in Cape Town from the widow of Colonel Gordon, commander of the Dutch garrison. When Waterhouse landed in Sydney, he sold his sheep to Captain John MacArthur, Samuel Marsden and Captain William Cox.[19]

John and Elizabeth Macarthur

By 1810, Australia had 33,818 sheep.[20] John MacArthur (who had been sent back from Australia to England following a duel with Colonel Patterson) brought seven rams and one ewe from the first dispersal sale of King George III stud in 1804. The next year, MacArthur and the sheep returned to Australia, Macarthur to reunite with his wife Elizabeth, who had been developing their flock in his absence. Macarthur is considered the father of the Australian Merino industry; in the long term, however, his sheep had very little influence on the development of the Australian Merino.

Macarthur pioneered the introduction of Saxon Merinos with importation from the Electoral flock in 1812. The first Australian wool boom occurred in 1813, when the Great Dividing Range was crossed. During the 1820s, interest in Merino sheep increased. MacArthur showed and sold 39 rams in October 1820, grossing £510/16/5.[21] In 1823, at the first sheep show held in Australia, a gold medal was awarded to W. Riley ('Raby') for importing the most Saxons; W. Riley also imported cashmere goats into Australia.

Eliza and John Furlong

Two of Eliza Furlong's (sometimes spelt Forlong or Forlonge) children had died from consumption, and she was determined to protect her surviving two sons by living in a warm climate and finding them outdoor occupations. Her husband John, a Scottish businessman, had noticed wool from the Electorate of Saxony sold for much higher prices than wools from NSW. The family decided on sheep farming in Australia for their new business. In 1826, Eliza walked over 1,500 miles (2,400 km) through villages in Saxony and Prussia, selecting fine Saxon Merino sheep. Her sons, Andrew and William, studied sheep breeding and wool classing. The selected 100 sheep were driven (herded) to Hamburg and shipped to Hull. Thence, Eliza and her two sons walked them to Scotland for shipment to Australia. In Scotland, the new Australia Company, which was established in Britain, bought the first shipment, so Eliza repeated the journey twice more. Each time, she gathered a flock for her sons. The sons were sent to NSW, but were persuaded to stop in Tasmania with the sheep, where Eliza and her husband joined them.[22]

The Melbourne Age in 1908 described Eliza Furlong as someone who had 'notably stimulated and largely helped to mould the prosperity of an entire state and her name deserved to live for all time in our history' (reprinted Wagga Wagga Daily Advertiser January 27, 1989).[23]

John Murray

There were nearly 2 million sheep in Australia by 1830, and by 1836, Australia had won the wool trade war with Germany, mainly because of Germany's preoccupation with fineness. German manufacturers commenced importing Australian wool in 1845.[24] In 1841, at Mount Crawford in South Australia, Murray established a flock of Camden-blood ewes mated to Tasmanian rams. To broaden the wool and give the animals some size, it is thought some English Leicester blood was introduced. The resultant sheep were the foundation of many South Australian strong wool studs. His brother Alexander Borthwick Murray was also a highly successful breeder of Merino sheep.[25]

The Peppin brothers

The Peppin brothers took a different approach to producing a hardier, longer-stapled, broader wool sheep. After purchasing Wanganella Station in the Riverina, they selected 200 station-bred ewes that thrived under local conditions and purchased 100 South Australian ewes bred at Cannally that were sired by an imported Rambouillet ram. The Peppin brothers mainly used Saxon and Rambouillet rams, importing four Rambouillet rams in 1860.[26] One of these, Emperor, cut an 11.4 lb (5.1 kg clean) wool clip. They ran some Lincoln ewes, but their introduction into the flock is undocumented. In 1865, George Merriman founded the fine wool Merino Ravensworth Stud, part of which is the Merryville Stud at Yass, New South Wales.[18]

Vermont sheep

In the 1880s, Vermont rams were imported into Australia from the U.S.; since many Australian stud men believed these sheep would improve wool cuts, their use spread rapidly. Unfortunately, the fleece weight was high, but the clean yield low, the greater grease content increased the risk of fly strike, they had lower uneven wool quality, and lower lambing percentages. Their introduction had a devastating effect on many famous fine-wool studs.

In 1889, while Australian studs were being devastated by the imported Vermont rams, several U.S. Merino breeders formed the Rambouillet Association to prevent the destruction of the Rambouillet line in the U.S. Today, an estimated 50% of the sheep on the U.S. western ranges are of Rambouillet blood.[16]

The federation drought (1901–1903) reduced the number of Australian sheep from 72 to 53 million and ended the Vermont era. The Peppin and Murray blood strain became dominant in the pastoral and wheat zones of Australia.

Current situation

In Australia today, a few Saxon and other fine-wool, German bloodline, Merino studs exist in the high rainfall areas.[27] In the pastoral and agriculture country, Peppins and Collinsville (21 to 24 micron) are popular.

In the drier areas, one finds the Collinsville (21 to 24 micron) strains. The development of the Merino is entering a new phase: objective fleece measurement and BLUP is now being used to identify exceptional animals. Artificial insemination and embryo transfer are being used to accelerate the spread of their genes. The result is a wide outcrossing between all major strains.

High price records

The world record price for a ram was A$450,000 for JC&S Lustre 53, which sold at the 1988 Merino ram sale at Adelaide, South Australia.[28] In 2008, an Australian Merino ewe was sold for A$14,000 at the Sheep Show and auction held at Dubbo, New South Wales.[29]

Events

The New England Merino Field Days, which display local studs, wool, and sheep, are held during January in even numbered years in and around the Walcha, New South Wales district.[30] The Annual Wool Fashion Awards, which showcase the use of Merino wool by fashion designers, are hosted by the city of Armidale, New South Wales in March each year.[31]

Animal welfare developments

In Australia, mulesing of Merino sheep is a common practice to reduce the incidence of flystrike. It has been attacked by animal rights and animal welfare activists, with PETA running a campaign against the practice in 2004. The PETA campaign targeted U.S. consumers by using graphic billboards in New York City. PETA threatened U.S. manufacturers with television advertisements showing their companies' support of mulesing. Fashion retailers including Abercrombie & Fitch Co., Gap Inc and Nordstrom and George (UK) stopped stocking Australian Merino wool products.[32]

The Animal Welfare Advisory Committee to the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture Code of recommendations and minimum standards for the welfare of Sheep, considers mulesing a "special technique" which is performed on some Merino sheep at a small number of farms in New Zealand.[33]

In 2008, mulesing once again became a topical issue in Sweden, with a documentary on mulesing shown on Swedish television.[34] This was followed by allegations of bribery and intimidation by Australian government and wool industry officials;[35] the allegations were disputed by the wool industry.[36] Several European clothing retailers, including H&M, stopped stocking products made with Merino wool from Australia.[37]

New strains of Merinos that do not require mulesing are being promoted in South Australia.[38]

'Thin-skinned' sheep from western Victoria are also being promoted as a solution.

See also

- Arkhar-Merino, a crossbreed with wild Urials

- Booroola Merino, prolific Merino strain

- Delaine Merino

- Peppin Merino, dominant Australian Merino strain

- Poll Merino

- Rambouillet (sheep)

References

- ↑ "Merino wool". Oviedo, Florida: NuMei. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ↑ Corominas, Joan; Pascual, José A., eds. (1989). "Merino". Diccionario Crítico Etimológico Castellano e Hispánico. IV. Madrid: Gredos. ISBN 84-249-0066-9.

- ↑ The Macquarie Dictionary. North Ryde: Macquarie Library. 1991.

- ↑ "Breeds of Livestock - German Mutton Merino Sheep". Ansi.okstate.edu. 1998-12-10. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ↑ "Will a Sheep's Wool Grow Forever?", Modern Farmer

- ↑ Australian Wool Classing, Australian Wool Corporation, 1990, p. 26

- ↑ Possumly fashion Retrieved on 14 October 2008

- 1 2 Waterproof Breathable Active Sports Wear Fabrics Retrieved 2009-12-19

- 1 2 D’Arcy, J.B., Sheep Management & Wool Technology, NSW University Press, 1986, ISBN 0-86840-106-4

- ↑ "Lanolin, Wool and Hand Cream". Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Marshall, A.J.T., Woolclassing, Trust Publication, 1984, ISBN 0-7244-9890-7

- ↑ "Gear Assistant, Outdoor Gear Resource".

- ↑ "Wool". The New American Cyclopaedia. 16. D. Appleton and Company. 1858. p. 538.

- ↑ Paterson, Mark (1990). National Merino Review. West Perth, Australia: Farmgate Press. pp. 12–17. ISSN 1033-5811.

- ↑ "Agriculture". Icenographic Encyclopedia of Science. 4. D. Appleton and Company. 1860. p. 731.

- 1 2 Ross, C.V. (1989). Sheep production and Management. Engleworrd Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 26–27. ISBN 0-13-808510-2.

- ↑ "Vermont Historical Society - William Jarvis's Merino Sheep". Vermonthistory.org. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- 1 2 McCosker, Malcolm, Heritage Merino, Owen Edwards Publications, West End, 1988 ISBN 0-9588612-3-4

- ↑ Lewis, Wendy, Simon Balderstone and John Bowan (2006). Events That Shaped Australia. New Holland. ISBN 978-1-74110-492-9.

- ↑ The Edinburgh Gazetteer, volume 1, Archibald Constable and Co.: Edinburgh, 1822, p.570

- ↑ The Australian Merino, Charles Massey,Viking O'Neil, South Yarra, 1990, p.62

- ↑ ADB: Forlong, Eliza (1784 - 1859) Retrieved 2009-11-28

- ↑ Mary S. Ramsay, 'Forlong, Eliza (1784 - 1859)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Supplementary Volume, Melbourne University Press, 2005, pp 130-131.

- ↑ Taylor, Peter, Pastoral Properties of Australia, George Allen & Unwin, Sydney, London, Boston,1984

- ↑ "S.A. Merino Rams in Queensland". The South Australian Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1858 - 1889). Adelaide, SA: National Library of Australia. 19 June 1861. p. 2. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- ↑ J. Ann Hone, 'Peppin, George Hall (1800 - 1872)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 5, Melbourne University Press, 1974, pp 430-431.

- ↑ The Australian Merino, Charles Massey, Viking O'Neil, South Yarra, 1990, p. 405

- ↑ Stock and Land Retrieved on 2008-9-8

- ↑ The Land, Rural Press, North Richmond, NSW, 4 September 2008

- ↑ New England Merino Field Days Retrieved 2010-1-9

- ↑ The Australian Wool Fashion Awards Retrieved 2010-1-9

- ↑ "Abercrombie & Fitch Pledges Not to Use Australian Merino Wool Until Mulesing and Live Exports End". PETA.org. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ↑ Code of recommendations and minimum standards for the welfare of Sheep Archived June 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Swedish consumers 'concerned' by mulesing". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 7 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ↑ "Bribe claim rocks wool trade body". The Age. 8 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ↑ "ABC misreports Swedish TV mulesing program". The Australian Wool and Sheep Industry Taskforce. 12 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ↑ "H&M Stops Selling Australian Wool | Ethisphere™ Institute". Ethisphere.com. 2008-02-19. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ↑ "Scientists search for bare-bum sheep gene". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 21 March 2005. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

Further reading

- Cottle, D.J. (1991). Australian Sheep and Wool Handbook. Melbourne, Australia: Inkata Press. pp. 20–23. ISBN 0-909605-60-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Merino. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1921 Collier's Encyclopedia article Merino. |

- Oklahoma State University - Merino reference page

- The American Delaine & Merino Record Association

- The American Rambouillet Sheep Breeders Association

- The Australian Association of Stud Merino Breeders

- New Zealand Merino Stud Breeders