Mikhail Nesterov

| Mikhail Vasilyevich Nesterov | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Viktor Vasnetsov (1926) | |

| Born |

31 May 1862 Ufa, Russian Empire |

| Died |

18 October 1942 (aged 80) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Education | Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, Imperial Academy of Arts |

| Known for | Painter |

| Movement | Russian Symbolism |

| Patron(s) | Savva Mamontov |

Mikhail Vasilyevich Nesterov (Russian: Михаи́л Васи́льевич Не́стеров; 31 May [O.S. 19 May] 1862, Ufa – 18 October 1942, Moscow) was a Russian and Soviet painter; associated with the Peredvizhniki and Mir Iskusstva. He was one of the first exponents of Symbolist art in Russia.

Biography

He was born to a strongly patriarchal merchant family. His father was a draper and haberdasher, but always had a strong interest in history and literature. As a result, he was sympathetic to his son's desire to be an artist, but insisted that he acquire practical skills first and, in 1874, he was sent to Moscow where he enrolled at the Voskresensky Realschule.

In 1877, his counselors suggested that he transfer to the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, where he studied with Pavel Sorokin, Illarion Pryanishnikov and Vasily Perov,[1] who was his favorite teacher. In 1879, he began to participate in the school's exhibitions. Two years later, he entered the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, where he worked with Pavel Chistyakov. He was disappointed at the teaching there and returned to Moscow, only to find Perov on his deathbed, so he took lessons from Alexei Savrasov.[2]

After a brief stay in Ufa, where he met his future wife, Maria, he returned to Moscow and studied with Vladimir Makovsky.[1] While creating a series of historical paintings, he supported himself doing illustrations for magazines and books published by Alexei Stupin, including a collection of fairy tales by Pushkin. In 1885, he was awarded the title "Free Artist" and married, against his parent's wishes. The following year, his wife died after giving birth to his daughter, Olga.[2] Several of his works from this period feature his wife's image.

His first major success came with his painting, "The Hermit" which was shown at the seventeenth exhibition of the Peredvizhniki in 1889. It was purchased by Pavel Tretyakov and the money enabled Nesterov to take an extended trip to Austria, Germany, France and Italy. Upon returning, his painting, "The Vision to the Youth Bartholomew", the first in a series of works on the life of Saint Sergius, was shown at the eighteenth Peredvizhniki exhibition and also purchased by Tretyakov. This series would eventually include fifteen large canvases and occupy him for fifty years.

Religious art

In 1890, Adrian Prakhov, who was overseeing work at St Volodymyr's Cathedral, became familiar with Nesterov's paintings and invited him to participate in creating murals and icons there. After some hesitation, he agreed, then travelled to Rome and Istanbul to acquaint himself with Byzantine art.[2] This project would take twenty-two years to complete. Although it brought him great popularity, he apparently came to feel that the images required were too clichéd and beneath his dignity as an artist, so he occasionally introduced some minor innovations, such as setting portraits of saints in a recognizable landscape.

Despite this, he undertook other religious commissions. In 1898, Grand Duke George Alexandrovich asked him to work at the Alexander Nevsky church in Abastumani.[2] He spent six years there, off and on, creating 50 small murals and the iconostasis, but was dissatisfied with the results. He was apparently much more pleased with later work at the Marfo-Mariinsky Convent. He refused to work on the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, Warsaw, because he did not approve of building an Orthodox cathedral in a predominantly Catholic city.[3]

In 1901, he wanted to deepen his spiritual appreciation of the monastic life, so he spent some time at the Solovetsky Monastery on the coast of the White Sea.[2] He painted numerous works there and the influence of his visit could be seen in his canvases for many years after. He was also inspired by the novels of Pavel Ivanovich Melnikov, dealing with the lives of the Old Believers in the Volga Region. In 1902, he married Ekaterina Vasilyeva, whom he had met admiring his works at an exhibition.

Later years

In 1905, after the Revolution began, he joined the Union of the Russian People, an extreme right-wing nationalist party that supported the Tsar. As a result, he was in some danger after the October Revolution. In 1918, he moved to Armavir, where he became ill and was unable to work. He returned to Moscow in 1920 and was forced to give up religious painting, although he continued to work on his Saint Sergius series in private. From then until his death, he painted mostly portraits; notably Ivan Ilyin, Ivan Pavlov, Otto Schmidt, Sergei Yudin, Alexey Shchusev and Vera Mukhina.[1]

In 1938, toward the end of the Great Purge, his son-in-law, Vladimir Schroeter, a prominent lawyer, was accused of being a spy and shot. His daughter was sent to a prison camp in Zhambyl, where she was brutally interrogated before being released. He was also arrested and held for two weeks at Butyrka Prison.[2]

In 1941, he was awarded the Stalin Prize for his portrait of Pavlov (created in 1935). It was one of the first given to an artist. Shortly after, he received the Order of the Red Banner of Labour. As the war progressed, his health and financial situation deteriorated rapidly. He had a stroke while working on his painting "Autumn in the Village" and died at Botkin Hospital.

His unfinished memoirs, which he had begun in 1926, were published later that year under the title "Bygone Days". In 1962, he was honored with a postage stamp. In 1996, his likeness appeared on the 50 Ural franc banknote and, in 2015, a monument to him was unveiled at the Bashkir State Art Museum in Ufa.

Gallery

- Holy Rus, 1901–06

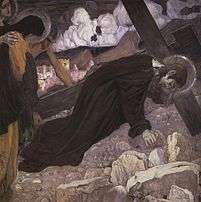

Crucifixion, 1912

Crucifixion, 1912 Taking the Veil, 1897–98

Taking the Veil, 1897–98 The Love Potion, 1888

The Love Potion, 1888 The Vision to the Youth Bartholomew, 1889-1890

The Vision to the Youth Bartholomew, 1889-1890 Beyond the Volga, 1905

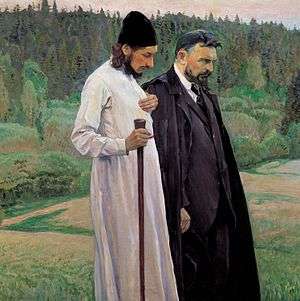

Beyond the Volga, 1905 Philosophers, 1917 (Pavel Florensky and Sergei Bulgakov)

Philosophers, 1917 (Pavel Florensky and Sergei Bulgakov) Tolstoy, 1906 (Leo Tolstoy)

Tolstoy, 1906 (Leo Tolstoy) Three old men with a fox, 1914

Three old men with a fox, 1914

In Rus. The Soul of the People. The last religious symbolic painting Nesterov painted before the revolution. The Russian people are following a young boy, while an old holy fool stays aside, praying ecstatically, wearing no clothes and possibly issuing a warning.

In Rus. The Soul of the People. The last religious symbolic painting Nesterov painted before the revolution. The Russian people are following a young boy, while an old holy fool stays aside, praying ecstatically, wearing no clothes and possibly issuing a warning.

References

- 1 2 3 Brief biography @ Russian Paintings.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Brief biography @ RusArtNet.

- ↑ Biographical notes by Sergei Durylin @ Bibliotekar.

Further reading

- Art Masters # 157: Mikhail Nesterov, Kipepeo Publishing, 2016 ISBN 978-1-52321-093-0

- Art Masters # 158: Mikhail Nesterov 2, Kipepeo Publishing, 2016 ISBN 978-1-52321-176-0

- Sergei Nikolayevich Durylin, Нестеров-портретист. (Nesterov-Portraitist), Искусство, 1949

- Alexei Ivanovich Mikhailov, М. В. Нестеров. Жизнь и творчество (Life and Works), Советский художник 1958.

- Anna Alexandrovna Rusakova, Михаил Нестеров, Аврора, 1990 ISBN 5-7300-0015-4

- Ekaterina Malinina, Михаил Нестеров, Masters of Art series, Белый город, 2008 ISBN 978-5-7793-1467-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mikhail Nesterov. |

- Mikhail Nesterov website

- Articles from the Tretyakov Gallery magazine, in English:

- "Quiet Truths" by Pavel Klimov

- "Mikhail Nesterov's Family in His Art" by Olga Ivanova

- "Nesterov and Ufa" by Svetlana Ignatenko

- "Mikhail Nesterov in Search of His Russia" by Lydia Iovleva

- "Mikhail Nesterov as Muralist and Icon Painter" by Anastasia Bubchikova

- "The Portraits of Mikhail Nesterov" by Lyudmila Bobrovskaya

- "From Biography to Hagiography. The Russian Intelligentsia in Mikhail Nesterov's Work" by Olga Atroshchenko

- The Alexander Nevsky Church in Abastumani.