Antonine Wall

| ||||

| Part of a series on the | ||||

| Military of ancient Rome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural history | ||||

|

||||

| Campaign history | ||||

| Technological history | ||||

|

||||

| Political history | ||||

|

|

||||

| Strategy and tactics | ||||

|

||||

|

| ||||

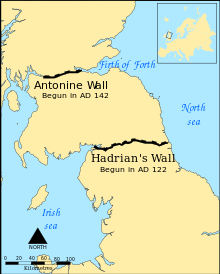

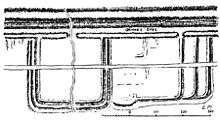

The Antonine Wall, known to the Romans as Vallum Antonini, was a turf fortification on stone foundations, built by the Romans across what is now the Central Belt of Scotland, between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde. Representing the northernmost frontier barrier of the Roman Empire, it spanned approximately 63 kilometres (39 miles) and was about 3 metres (10 feet) high and 5 metres (16 feet) wide. Security was bolstered by a deep ditch on the northern side. It is thought that there was a wooden palisade on top of the turf. The barrier was the second of two "great walls" created by the Romans in Northern Britain. Its ruins are less evident than the better-known Hadrian's Wall to the south, primarily because the turf and wood wall has largely weathered away, unlike its stone-built southern predecessor.

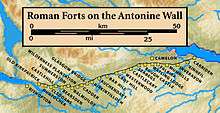

Construction began in AD 142 at the order of Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius, and took about 12 years to complete. Antoninus Pius never visited the British Isles, whereas his predecessor Hadrian did. Pressure from the Caledonians may have led Antoninus to send the empire's troops further north. The Antonine Wall was protected by 16 forts with small fortlets between them; troop movement was facilitated by a road linking all the sites known as the Military Way. The soldiers who built the wall commemorated the construction and their struggles with the Caledonians in decorative slabs, twenty of which still survive. The wall was abandoned only eight years after completion, and the garrisons relocated back to Hadrian's Wall. In 208 Emperor Septimius Severus re-established legions at the wall and ordered repairs; this has led to the wall being referred to as the Severan Wall. The occupation ended a few years later, and the wall was never fortified again. Most of the wall and its associated fortifications have been destroyed over time, but some remains are still visible. Many of these have come under the care of Historic Scotland and the UNESCO World Heritage Committee.

Location and construction

Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius ordered the construction of the Antonine Wall around 142.[1] Quintus Lollius Urbicus, governor of Roman Britain at the time, initially supervised the effort, which took about twelve years to complete.[2] The wall stretches 63 kilometres (39 miles) from Old Kilpatrick in West Dunbartonshire on the Firth of Clyde to Carriden near Bo'ness on the Firth of Forth. The wall was intended to extend Roman territory and dominance by replacing Hadrian's Wall 160 kilometres (99 miles) to the south, as the frontier of Britannia. But while the Romans did establish many forts and temporary camps further north of Antonine's wall in order to protect their routes to the north of Scotland, they did not conquer the Caledonians, and the Antonine Wall suffered many attacks. The Romans called the land north of the wall Caledonia, though in some contexts the term may refer to the whole area north of Hadrian's Wall.

The Antonine Wall was shorter than Hadrian's Wall and built of turf on a stone foundation rather than of stone, but it was still an impressive achievement. The stone foundations and wing walls of the original forts demonstrate that the original plan was to build a stone wall similar to Hadrian's Wall, but this was quickly amended. As built, the wall was typically a bank, about four metres (13 feet) high, made of layered turves and occasionally earth with a wide ditch on the north side, and a military way on the south. The Romans initially planned to build forts every 10 kilometres (6 miles), but this was soon revised to every 3.3 kilometres (2 miles), resulting in a total of nineteen forts along the wall. The best preserved but also one of the smallest forts is Rough Castle Fort. In addition to the forts, there are at least 9 smaller fortlets, very likely on Roman mile spacings, which formed part of the original scheme, some of which were later replaced by forts.[3] The most visible fortlet is Kinneil, at the eastern end of the Wall, near Bo'ness.[4]

There was once a remarkable Roman structure within sight of the Antonine Wall at Stenhousemuir. This was Arthur's O'on, a circular stone domed monument or rotunda, which may have been a temple, or a tropaeum, a victory monument. It was demolished for its stone in 1743, though a replica exists at Penicuik House.

In addition to the line of the Wall itself there are a number of coastal forts both in the East (e.g. Inveresk) and West (Outerwards and Lurg Moor), which should be considered as outposts and/or supply bases to the Wall itself. In addition a number of forts farther north were brought back into service in the Gask Ridge area, including Ardoch, Strageath, Bertha[3] and probably Dalginross and Cargill.[5]

Abandonment

The wall was abandoned only eight years after completion, when the Roman legions withdrew to Hadrian's Wall in 162, and over time may have reached an accommodation with the Brythonic tribes of the area, whom they may have fostered as possible buffer states which would later become "The Old North". After a series of attacks in 197, the emperor Septimius Severus arrived in Scotland in 208 to secure the frontier, and repaired parts of the wall. Although this re-occupation only lasted a few years, the wall is sometimes referred to by later Roman historians as the Severan Wall. This led to later scholars like Bede mistaking references to the Antonine Wall for ones to Hadrian's Wall.

Post-Roman history

Gildas and Bede

Writing in AD 730, Bede following Gildas mistakenly ascribes the construction of the Antonine Wall to the Britons in Historia Ecclesiastica 1.12:

The islanders built the wall which they had been told to raise, not of stone, since they had no workmen capable of such a work, but of sods, made it of no use. Nevertheless, they carried it for many miles between the two bays or inlets of the sea of which we have spoken; to the end that where the protection of the water was wanting, they might use the rampart to defend their borders from the irruptions of the enemies. Of the work there erected, that is, of a rampart of great breadth and height, there are evident remains to be seen at this day [AD 730]. It begins at about two miles distance from the monastery of Aebbercurnig [Abercorn], west of it, at a place called in the Pictish language Peanfahel, but in the English tongue, Penneltun [Kinneil], and running westward, ends near the city of Aicluith [Dumbarton]. (Bede Historia Ecclesiastica Book I Chapter 12)

Bede associated Gildas' turf wall with the Antonine Wall. As for Hadrian's Wall, Bede again follows Gildas:

[the departing Romans] thinking that it might be some help to the allies [Britons], whom they were forced to abandon, constructed a strong stone wall from sea to sea, in a straight line between the towns that had been there built for fear of the enemy, where Severus also had formerly built a rampart. (Bede Historia Ecclesiastica Book I Chapter 12)

Bede obviously identified Gildas' stone wall as Hadrian's Wall, but he sets its construction in the 5th century rather than the 120s, and does not mention Hadrian. And he would appear to have deduced that the ditch-and-mound barrier known as the Vallum (just to the south of, and contemporary with, Hadrian's Wall) was the rampart constructed by Severus. Many centuries would pass before just who built what became apparent.[6]

Grim's Dyke

In medieval histories, such as the chronicles of John of Fordun, the wall is called Gryme's dyke. Fordun says that the name came from the grandfather of the imaginary king Eugenius son of Farquahar. This evolved over time into Graham's dyke – a name still found in Bo'ness at the wall's eastern end – and then linked with Clan Graham. Of note is that Graeme in some parts of Scotland is a nickname for the devil, and Gryme's Dyke would thus be the Devil's Dyke, mirroring the name of the Roman Limes in Southern Germany often called 'Teufelsmauer'. Grímr and Grim are bynames for Odin or Wodan, who might be credited with the wish to build earthworks in unreasonably short periods of time. This name is the same one found as Grim's Ditch several times in England in connection with early ramparts: for example, near Wallingford, Oxfordshire or between Berkhamsted (Herts) and Bradenham (Bucks). Other names used by antiquarians include the Wall of Pius and the Antonine Vallum, after Antoninus Pius.[7][8] Hector Boece in his 1527 History of Scotland called it the "wall of Abercorn", repeating the story that it had been destroyed by Graham.[9]

World Heritage status

The UK government's nomination of the Antonine Wall for World Heritage status to the international conservation body UNESCO was first officially announced in 2003.[10] It has been backed by the Scottish Government since 2005[11] and by Scotland's then Culture Minister Patricia Ferguson since 2006.[12] It became the UK's official nomination in late January 2007,[13] and MSPs were called to support the bid anew in May 2007.[14] The Antonine Wall was listed as an extension to the World Heritage Site "Frontiers of the Roman Empire" on 7 July 2008.[15][16] Though the Antonine Wall is mentioned in the text, it does not appear on UNESCO's map of world heritage properties.[17]

Historic Scotland

Several individual sites along the line of the wall are in the care of Historic Scotland. These are:

- Bar Hill Fort

- Bearsden Bath House

- Castlecary

- Croy Hill

- Dullatur

- Rough Castle

- Seabegs Wood

- Watling Lodge

- Westerwood

All sites are unmanned and open at all reasonable times.[18] See also Category:Ancient Roman forts in Scotland.

Mapping the wall

The first capable effort to systematically map the Antonine Wall was undertaken in 1764 by William Roy,[19] the forerunner of the Ordnance Survey. He provided accurate and detailed drawings of its remains, and where the wall has been destroyed by later development, his maps and drawings are now the only reliable record of it.

In fiction

The Northern Wall is depicted in some of Rosemary Sutcliff's historical fiction novels; as a fully functioning outpost of Roman power in The Mark of the Horse Lord, and as an abandoned ruin in Frontier Wolf. The Antonine Wall is also mentioned in World War Z as the last line of defense in Great Britain against the zombies.

Invasion

The Picts were able to repeatedly break through and breach many ancient walls such as the Antonine Wall.

See also

- Gask Ridge

- Trimontium

- Scotland during the Roman Empire

- World Heritage Sites in Scotland

- National Museums of Scotland

- The Bridgeness Slab

References

- ↑ Robertson, Anne S. (1960) The Antonine Wall. Glasgow Archaeological Society. p. 7.

- ↑ Breeze, David J. (2006) The Antonine Wall. Edinburgh. John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-655-1 p. 167.

- 1 2 L.Keppie, Scotland's Roman Remains. Edinburgh 1986)

- ↑ Historic Scotland - Looking after our heritage - The Antonine Wall

- ↑ D.J.Woolliscroft & B.Hoffmann, Romes First Frontier. The Flavian occupation of Northern Scotland (Stroud: Tempus 2006)

- ↑ , From Dot to Domesday website

- ↑ Earthwork of England: prehistoric, Roman, Saxon, Danish, Norman and mediæval - Page 496, by Arthur Hadrian Allcroft

- ↑ 'Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club - Page 255, by Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club, Hereford, England, G. H. Jack, 1905

- ↑ Boece, Hector, Historia Gentis Scotorum, (1527), book 7, chapter 16

- ↑ "Roman wall builds heritage claim". BBC News. 22 February 2003. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ↑ "Roman wall heritage bid backing". BBC News. 14 June 2005. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ↑ "World Heritage bid hope for wall". BBC News. 20 June 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ↑ "World Heritage support for wall". BBC News. 23 January 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ↑ "MSPs called to support Roman wall". BBC News. 23 May 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage Centre. New Inscribed Properties

- ↑ "Wall gains World Heritage status'" BBC News. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ↑ Frontiers of the Roman Empire - UNESCO World Heritage Centre

- ↑ Historic Scotland - Antonine Wall: Overview Property Detail

- ↑ Hübner, Emil (1886). "The Roman Annexation of Britain". In Hodgkin, Thomas. Archaeologia Aeliana. New. XI. Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne. pp. 82–116.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Antonine Wall. |

- Antonine Wall – site information from Historic Environment Scotland

- http://www.antoninewall.org/

- http://www.antonine-way.co.uk

- http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/antoninewall

- http://www.kinneil.org.uk/attractions

- http://www.athenapub.com/antwall1.htm

- http://www.athenapub.com/britsite/hillfoot.htm

- http://www.theromangaskproject.org/

- https://web.archive.org/web/20060105025602/http://www.roman-britain.org:80/frontiers/antonine.htm

- https://web.archive.org/web/20030219165900/http://www.almac.co.uk:80/FalkirkTCM/Rome.htm

- The Antonine Wall and Bar Hill

- Richard Stillwell, ed. Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, 1976: "Antonine Wall, Scotland"

- Museum news

- Information on the Antonine Wall - Clyde Waterfront Heritage

- The Antonine Wall: Rome's Final Frontier, Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, Glasgow

Coordinates: 55°58′01″N 4°04′01″W / 55.967°N 4.067°W