Portable art

Portable art (sometimes called mobiliary art) refers to the small examples of Prehistoric art that could be carried from place to place, which is especially characteristic of the Art of the Upper Palaeolithic.[1] It is one of the two main categories of Prehistoric art, the other being the immobile Parietal art,[2] effectively synonymous with rock art.

Though the game hunted for food was a recurring subject within portable art, the over 10,000 pieces that have been discovered exhibit a great diversity in terms of scale, subject, use, date of creation, and media. Originally seen as less important than the cave paintings that also marked prehistoric art, portable art was thought to be merely preceding sketches or plans to be developed in later, larger parietal, or permanent, art. Over the years, however, the study of portable art has come into its own as archaeologists realize much information about prehistoric culture, livelihood, and societal structure can be gathered from these works or art.

Categories of Portable Art

- Slightly Modified Natural Objects

Usually composed of fossils, teeth, shells, and bone, slightly modified natural objects were pre-existing objects which prehistoric man altered by etching lines or patterns, drilling holes, or other simple techniques which changed the original object into a piece of artwork, typically jewellery.

- Engraved or Painted Stone

As many as 1,000 sites with instances of decorated stone have been discovered. Sandstone, limestone, slate, or stalagmite were the most common types of material employed, and were usually adorned with animal figures or symbols. Such pieces have been interpreted by some archaeologists to be predecessors serving as sketches to a later, more developed cave painting.

- Engraved or Painted Bone

Similar to engraved or painted stone works, the subjects of the bone pieces were typically game animals and symbols. Unlike their stone counterparts, however, decorated bone works are often much smaller in scale and are seen less frequently, as bone is much more difficult than stone to engrave.

- Carved Bone and Antler

Most frequently used in the carving of spear-throwers, carved bone and antler pieces are significant because of the great amount of time, effort, and painstaking detail with which they were carved. As a result, a common belief among archaeologists is that such works were crafted in the hopes of bringing good luck on a hunt.

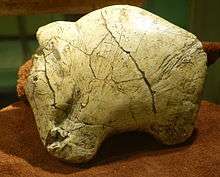

- Statuettes and Ivory Carvings

While it is the rounded female statuettes, dubbed venus figurines, that have garnered the most attention, sculpted objects also featured more "normal" human depictions, as well as that of animals. The statuettes and carvings were done using flint tools in a wide variety of materials, ranging from their simple inception as terracottas, to limestone, sandstone, ivory, stealite, coal, jet, and even amber.

Dating and its difficulty

The vast span of time, as long as 40,000 years in some cases, separating the creation of portable art and its subsequent analysis poses a great problem in dating the works. The typical method for dating ancient material, rardiocarbon dating, poses the possibility of destroying the piece, and also only works to date the animal bone, antler, or other material with which the art was created, not the date that the art itself was created. A common solution to this problem has been to study instead the stratigraphy of the piece within the deposits of its surroundings. In many cases, however, even stratigraphical dating is impossible, due to the disregard early archaeologists gave when excavating the caves or other sites portable art were discovered in. The destruction of a datable stratigraphy also commonly occurred as a result from ransacking and illegal digs focused not on the study of the material they discovered, but on its re-sale value. All disruptions of the stratigraphy destroy the provenance from which a date could be established.

Also posing a difficulty to stratigraphical analysis is the possibility that the time of an object's creation and final deposit can vary greatly. Many portable objects are believed to have served as ritual objects, being passed down from generation to generation, keeping them in use for hundreds or thousands of years. Through the migration of prehistoric man, it is possible that the final resting place of an object is hundreds or even thousands of miles from the point of its original creation.

Though difficult, dating portable objects provides an important link in building a chronology of the art, and thus evolution of prehistoric man. While the specific trends associated with a given period are not always agreed on among all scientists due to the subjective nature of art, broad similarities and patterns can be formed which work to augment the archaeological study or prehistoric man by forming observations and theories on which other archaeologists can develop.

References

- ↑ Scarre, Chris (2009). The Human Past. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-500-28780-4.

- ↑ Bahn, Paul (1998). The Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. xxiv. ISBN 0-521-45473-5.