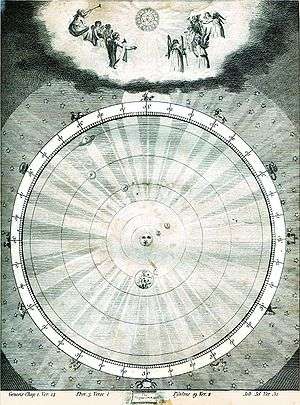

Musica universalis

Musica universalis (literally universal music), also called Music of the spheres or Harmony of the Spheres, is an ancient philosophical concept that regards proportions in the movements of celestial bodies—the Sun, Moon, and planets—as a form of musica (the Medieval Latin term for music). This "music" is not usually thought to be literally audible, but a harmonic, mathematical or religious concept. The idea continued to appeal to thinkers about music until the end of the Renaissance, influencing scholars of many kinds, including humanists. Further scientific exploration has determined specific proportions in some orbital motion, described as Orbital resonance.

History

It is attributed to Pythagoras the discovery of the relation between the pitch of the musical note and the length of the string that produces it. The Music of the Spheres incorporates the metaphysical principle that mathematical relationships express qualities or "tones" of energy which manifest in numbers, visual angles, shapes and sounds – all connected within a pattern of proportion. Pythagoras first identified that the pitch of a musical note is in proportion to the length of the string that produces it, and that intervals between harmonious sound frequencies form simple numerical ratios.[1] In a theory known as the Harmony of the Spheres, Pythagoras proposed that the Sun, Moon and planets all emit their own unique hum (orbital resonance) based on their orbital revolution,[2] and that the quality of life on Earth reflects the tenor of celestial sounds which are physically imperceptible to the human ear.[3] Subsequently, Plato described astronomy and music as "twinned" studies of sensual recognition: astronomy for the eyes, music for the ears, and both requiring knowledge of numerical proportions.[4]

Is Aristotle the first in giving a critical exposition of the pythagorean notion of the harmony of the spheres. “We should see evidently, after all that procedes, that, when they talk to us about a harmony resultant of the movement of those bodies, same as the harmony of the sounds that are entwined, there is brilliant comparison being done undoubtedly, but vain; that is not the truth nowise. There are indeed people [the pythagoreans] that figures out that the movement of bodies so big (the planets) must produce necessarily noise, because we hear all around us the noises that bodies without mass nor a speed as equal as the Sun of the Moon. Because of that, one believes being authorized to conclude that stars so numerous and immense cannot go by there making translations moves without making any intense noise. Admitting at first this hypothesis, and supposing that these bodies, thanks to its respective distances, they are for its speed in the same proportion than harmonies, this philosophers come to pretend that the star's voice, which moves into circles, is harmonious. But as it would be very surprising that we did not hear that pretentious voice, it explain us the cause, saying that noise is in our ears since our birth date. This causes that we cannot tell the noise, the thing is, we have never had the contrast of silence which would be its opposite: because voice and silence make themselves distinguishable the one to the other".

Esoteric Christianity

The three branches of the Medieval concept of musica were presented by Boethius in his book De Musica:[5]

- musica mundana (sometimes referred to as musica universalis)

- musica humana (the internal music of the human body)

- musica quae in quibusdam constituta est instrumentis (sounds made by singers and instrumentalists)

According to Max Heindel's Rosicrucian writings, the heavenly "music of the spheres" is heard in the Region of Concrete Thought, the lower region of the mental plane, which is an ocean of harmony.

It is also referred to in Esoteric Christianity as the place where the state of consciousness known as the "Second Heaven" occurs.

Use in recent music

The connection between music, mathematics, and astronomy had a profound impact on history. It resulted in music's inclusion in the Quadrivium, the medieval curriculum that included arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy, and along with the Trivium (grammar, logic,and rhetoric) made up the seven free arts, which are still the basis for higher education today. A small number of recent compositions either make reference to or are based on the concepts of Musica Universalis or Harmony of the Spheres. Among these are Music of the Spheres by Mike Oldfield, Om by the Moody Blues, The Earth Sings Mi Fa Mi album by The Receiving End of Sirens and Björk's single Cosmogony, included in her 2011 album Biophilia. Earlier, in the 1910s, Danish composer Rued Langgaard composed a pioneering orchestral work titled Music of the Spheres.

See also

- Asteroseismology

- Esoteric cosmology

- Harmonices Mundi

- Orbital resonance

- This Is My Father's World

- Titius–Bode law

- Ray of Creation

- Sacred geometry

- Shabd

Notes

- ↑ Weiss and Taruskin (2008) p.3.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder (77) pp.277-8, (II.xviii.xx): "…occasionally Pythagoras draws on the theory of music, and designates the distance between the Earth and the Moon as a whole tone, that between the Moon and Mercury as a semitone, .... the seven tones thus producing the so-called diapason, i.e.. a universal harmony".

- ↑ Houlding (2000) p.28: For Philolaus, mathematician and pythagorean astronomer, year 400 b.F.; the world is «harmony and numbers», all is in order according to proportions that tally to three basic tunes for the music: 2:1 (harmony), 3:2 (fifth), 4:3 (fourth). Nicomachus of Gerasa (also pythagorean, towards the year 200) assigns the notes of the octave to the celestial bodies, so that they generate a music. "The doctrine of the Pythagoreans was a combination of science and mysticism… Like Anaximenes they viewed the Universe as one integrated, living organism, surrounded by Divine Air (or more literally 'Breath'), which permeates and animates the whole cosmos and filters through to individual creatures … By partaking of the core essence of the Universe, the individual is said to act as a microcosm in which all the laws in the macrocosm of the Universe are at work".

- ↑ Davis (1901) p.252. Plato’s Republic VII.XII reads: "As the eyes, said I, seem formed for studying astronomy, so do the ears seem formed for harmonious motions: and these seem to be twin sciences to one another, as also the Pythagoreans say".

- ↑ Boethius, De institutione musica, I.2 (p. 187 Friedlein ed.)

Sources

- Davis, Henry, 1901. The Republic The Statesman of Plato. London: M. W. Dunne 1901; Nabu Press reprint, 2010. ISBN 978-1-146-97972-6.

- Hackett, Jeremiah, 1997. Roger Bacon and the sciences: commemorative essays. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10015-2.

- Kepler, Johannes, 1619. The Harmony of the World, translated by E.J. Aiton, A.M. Duncan and J.V. Field (1997). Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-209-0.

- Pliny the Elder, 77AD. Natural History, books I-II, translated by H. Rackham (1938). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-99364-0.

- Smith, Mark A., 2006. Ptolemy's theory of visual perception: an English translation of the Optics. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-862-9.

- Soanes, Catherine, (ed.) 2006. The Oxford Dictionary of English 2nd ed. Oxford University Press: Oxford. ISBN 3-411-02144-6.

- Weiss, Piero and Taruskin, Richard, 2008. Music in the Western World: a history in documents. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-534-58599-0.

Further reading

- Calter, Paul. "Pythagoras & Music of the Spheres". Geometry in Art & Architecture. Dartmouth College. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- Plant, David. "Johannes Kepler & the Music of the Spheres". Skyscript.co.uk. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- Wille G. Musica Romana. Die Bedeutung der Musik im Leben der Römer. Amsterdam, 1967.

- Burkert W. Weisheit und Wissenschaft: Studien zu Pythagoras, Philolaos und Platon. Nürnberg, 1962

- Richter L. Tantus et tam dulcis sonus. Die Lehre von der Sphärenharmonie in Rom und ihre griechischen Quellen // Geschichte der Musiktheorie. Bd. 2. Darmstadt, 2006, SS.505-634.