Near side of the Moon

The near side of the Moon is the lunar hemisphere that is permanently turned towards the Earth, whereas the opposite side is the far side of the Moon. Only one side of the Moon is visible from Earth because the Moon rotates about its spin axis at the same rate that the Moon orbits the Earth, a situation known as synchronous rotation or tidal locking. The Moon is directly illuminated by the Sun, and the cyclically varying viewing conditions cause the lunar phases. The unilluminated portions of the Moon can sometimes be dimly seen as a result of earthshine, which is sunlight reflected off the surface of the Earth and onto the Moon. Since the Moon's orbit is both somewhat elliptical, and inclined to its equatorial plane, libration allows up to 59% of the Moon's surface to be viewed from Earth (but only half at any instant from any point).

Names

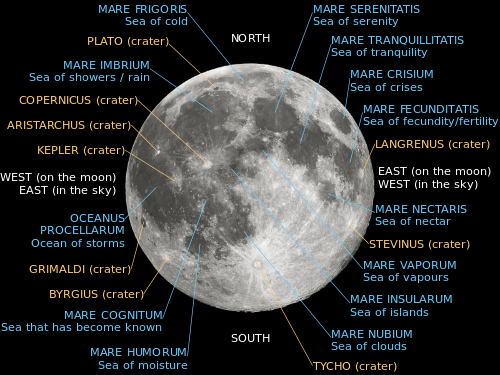

The near side of the Moon is characterized by large dark areas that were believed to be seas by the astronomers who first mapped them, in the 17th century (notably, Giovanni Battista Riccioli and Francesco Maria Grimaldi). Although it was found out later that the Moon has no seas, the term "mare" (plural: maria) is still used. The lighter toned regions are referred to as "terrae", or more commonly, the "highlands".[1]

Orientation

The image of the Moon here is drawn as is normally shown on maps, that is with north on top and west to the left. Astronomers usually turn the map over to have south on top, as to correspond with the view in most telescopes which also show the image upside down.

West and east on the Moon are where you would expect them, when standing on the Moon. But when we, on Earth, see the Moon in the sky, then the east–west direction is just reversed. When specifying coordinates on the Moon it should therefore always be mentioned whether geographic (or rather selenographic) coordinates are used or astronomical coordinates.

The actual orientation you see the Moon in the sky or on the horizon depends on your geographic latitude on Earth. In the following description a few typical cases will be considered.

- On the north pole, if the Moon is visible, it stands low above the horizon with its north pole up.

- In mid northern latitudes (North America, Europe, Asia) the Moon rises in the east with its northeastern limb up (Mare Crisium), it reaches its highest point in the south with its north on top, and sets in the west with its northwestern limb (Mare Imbrium) on top.

- On the equator, when the Moon rises in the east, its N — S axis appears horizontal and Mare Foecunditatis is on top. When it sets in the west, about 12.5 hours later, the axis is still horizontal, and Oceanus Procellarum is the last area to dip below the horizon. In between these events, the Moon reached its highest point in the zenith and then its selenographic directions are lined up with those on Earth.

- In mid southern latitudes (South America, South Pacific, Australia, South Africa) the Moon rises in the east with its southeastern limb up (Mare Nectaris), it reaches its highest point in the north with its south on top, and sets in the west with its southwestern limb (Mare Humorum) on top.

- On the south pole the Moon behaves as on the north pole, but there it appears with its south pole up.

Differences

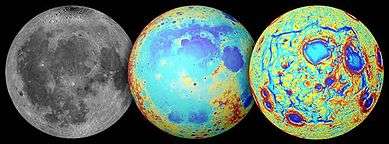

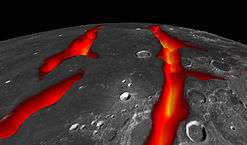

The two hemispheres have distinctly different appearances, with the near side covered in multiple, large maria (Latin for 'seas,' since the earliest astronomers incorrectly thought that these plains were seas of lunar water). The far side has a battered, densely cratered appearance with few maria. Only 1% of the surface of the far side is covered by maria,[2] compared to 31.2% on the near side. According to research analyzed by NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission, the reason for the difference is because the moon’s crust is thinner on the near side compared to the far side.[3] The dark splotches that make up the large lunar maria are lava-filled impact basins that were created by asteroid impacts about four billion years ago. Though both sides of the moon were bombarded by similarly large impactors, the near side hemisphere crust and upper mantle was hotter than that of the far side, resulting in the larger impact craters.[4] These larger impact craters make up the Man in the Moon references from popular mythology.

See also

References

- ↑ University of Tennessee

- ↑ J. J. Gillis; P. D. Spudis (1996). "The Composition and Geologic Setting of Lunar Far Side Maria". Lunar and Planetary Science. 27: 413–404. Bibcode:1996LPI....27..413G.

- ↑ Universe Today

- ↑ Science Magazine

External links

- Book: Craters of the Near Side Moon

- Lunar and Planetary Institute: Exploring the Moon

- Lunar and Planetary Institute: Lunar Atlases

- Ralph Aeschliman Planetary Cartography and Graphics: Lunar Maps

- NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) Mission