Newfoundland pine marten

| Newfoundland pine marten | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Genus: | Martes |

| Species: | M. americana |

| Trinomial name | |

| Martes americana atrata (Bangs, 1897)[1] | |

The Newfoundland pine marten (Martes americana atrata) is a genetically distinct subspecies of the American marten (Martes americana) found only on the island of Newfoundland in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada; it is sometimes referred to as the American marten (Newfoundland population) and is one of only 14 species of land mammals native to the island. The marten is listed as endangered by the COSEWIC in 2001 and has been protected since 1934, however the population still declines.[2] The Newfoundland marten has been geographically and reproductively isolated from the mainland marten population for 7000 years.[3] The Newfoundland pine marten is similar in appearance to its continental cousin, but is slightly larger, with dark brown fur with an orange/yellow patch on the throat.[4] Females are an average weight of 772 grams and males have an average weight of 1275 grams.[4] The Newfoundland subspecies is also observed to inhabit a wider range of forest types than its mainland counterparts. The population characteristics suggest that the Newfoundland marten is a product of unique ecological setting and evolutionary selective factors acting on the isolated island population.[3] The Newfoundland pine marten is omnivorous, feeding on mainly small mammals, along with birds, old carcasses, insects and fruits; it is currently found in suitable pockets of mature forest habitat, on the west coast of Newfoundland and in and around Terra Nova National Park.[5] The Pine Marten Study Area (PMSA) is located in southwestern Newfoundland and is a 2078 km2 wildlife reserve that was created in 1973 to protect the Newfoundland Marten.[3]

Habitat

The Newfoundland marten range is now condensed into approximately 13,000 square kilometers in the western part of the island, with a large portion of key habitat in the Little Grand Lake area.[6] Due to the unregulated pulpwood harvest during the last century, the forest age-class distribution is skewed to the younger regeneration stage of forest succession, which led to the majority of the island being contiguous blocks of second-growth forest.[7] The behavioral patterns of habitat use by Newfoundland martens are altered by the ecological conditions of low prey biomass and high natural forest fragmentation that occur in Newfoundland.[8] A wide spectrum of habitat types are used throughout the geographic range, however, it has been found the Newfoundland Marten has a strong association with old successional forest.[8] Old-growth forest is defined as unharvested stands that are older than 80 years of age.[9] The stand-scale habitat use includes mature coniferous forest being the dominant cover types used proportionately more than the availability, along with coniferous scrub and insect-defoliated stands used in proportion to the availability, whereas open areas and fire disturbed area are avoided.[8] However, the fire disturbance is minimized because of the lack of prolonged dry periods on the island.[7] Due to infrequent fires, the episodic defoliation by the spruce budworm and hemlock looper are the primary form of natural stand-replacing disturbance.[7] Newfoundland martens have a preference to mature (61–80 years old) and over mature (>80 years old) coniferous stands[10] since it is critical for foraging habitat.[7] More recent studies have found that martens will use forests with a variety of height and canopy closure conditions creating a wider variety of habitat types than previously thought; this variety includes areas that are disturbed by insects, mid-successional forests, precommercially thinned forests, along with the areas of mature and overmature forests.[4]

Home range requirements for the Newfoundland Marten are extremely large due to the larger body size.[3] Males hold larger home-ranges (29.54 km2) than females (15.19 km2) which are significantly larger than other species of martens across most of the geographic range.[8] These larger home-ranges reflect the larger body sizes and the lower diversity and abundance of prey.[8] Martens will also adjust their behavior and home-ranges to suit the habitat needs since the average home-range of the marten is typically larger than the average defoliate parch size and therefore will need to adjust for defoliation disturbance.[7] Newfoundland martens are also intrasexually territorial and show home-range fidelity.[10] Home-range size have variation between years for both sexes based on the changes in the food abundance as well as the individual's ability to obtain their prey.[8] Within the year, martens may modify their movements during the winter because it is an additional energetic constraint that they have to respond to the harsher weather conditions and lower resource availability.[8]

Newfoundland martens are forest-dependent species because they require overhead canopy for security and avoidance of predation, structurally complexity with abundant coarse woody debris and large diameter trees for winter resting sites, maternal dens, and access to small mammal prey in winter, as well as martens are more successful at catching prey in the older, structurally complex forest which is not necessarily where the prey are abundant.[10] The older coniferous forest is not needed just for escape from predation, prey availability, and den sites but also for thermoregulation.[7] Tree height is important to provide this thermally neutral area from resting sites as well as escape routes from predators.[11] Canopy closer is a critical element of marten habitat, studies have shown that the presence of vertical stem structure and down woody debris is adequate to provide the security needed even if over head cover is absent; though marten still typically avoid the areas that are devoid of trees.[7] Down logs and other woody debris are important to the marten habitat, not just for cover from predators, but also for access to prey and for suitable sites for resting and maternal dens.[8] The determinant of suitable habitat may be forest structure over the species composition or age.[10] The reduced number of larger mammalian predators on the island compared to mainland martens slightly reduces the necessity to have escape cover which releases the selective pressure for Newfoundland martens to expand their habitat into areas that have higher prey densities, but with less secure cover relative to the mainland populations of martens.[10]

Essentially the Newfoundland marten needs the jumble of dead and down timber that is provided by the old growth forests, where it allows for access under the snow during winter to small mammals providing the martens the resources needed to survive until spring; resources clearcuts cannot provide.[6] Habitat structure required for a healthy marten population needs decades to develop and have individual home range requirements that are large for the small carnivore.[7] Due to the changes in the stand-level dynamics and landscape-level phenomena shows that serious management is necessary to get the forests of Newfoundland to be prime habitat.[7] However, the conflict between the valuable economic resource of the timber and the preservation of the Newfoundland Marten will continue, suggesting that the system of permanent habitat reserves may not be a stable management strategy.[7]

Diet

Newfoundland has a small diversity of small mammal prey species, only topping out at 8.[8] Out of these 8 only three small mammal prey species are found within the marten's forested range, including: meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus), masked shrew (Sorex cinereus), and snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus).[7] Historically, meadow voles were thought to comprise the diet of the Newfoundland marten [10] because the meadow vole is the only endemic small mammal species that occurs in the forested habitat used by the martens.[8] New studies have shown that the Newfoundland Marten's diet is more generalized, with their diet in the winter being primarily Snowshoe Hare.[10] Hares occur at high densities in regenerating forests and meadow voles occur at low densities in the forests [10] and therefore the movement patterns of the Newfoundland marten may be a response to the fluctuating hare abundance in the habitat.[8] On the island, Meadow Voles occur in the coniferous forest as well as the open, grassy areas.[8] The Newfoundland martens primary diet in the summer consists of the meadow voles, and switch to primary diet of snowshoe hares by an increase of 10-fold.[10] A study showed that the Meadow Voles occurred at 80% of the diet during the summer, then dropping to 47.5% of the diet during the winter, where as Snowshoe Hare increased to 28% during the winter.[8] The introduced Snowshoe Hare is a critical food source during winter, which is the energetically stressful period during the year.[8] Other food types that are included in the marten's diet includes Masked Shrews, Red Squirrels, Moose and Caribou carrion, insects, birds, and berries, however, these food items only occur less than 10% of the overall diet.[8] During the summer with the primary food source being Meadow Voles, the next common food types was berries.[8] This study shows a highly diverse diet and a generalist foraging strategy for the use of available prey.[8]

Southern Red-backed Voles (Clethrionomys gapperi) may have been deliberately introduced to increase the small mammal prey population available for the Newfoundland Marten.[3] This management option was debated during the Newfoundland Marten recovery plan because the Southern Red-backed voles are a common prey for the American marten's diet elsewhere.[3] While the positive aspect is having a greater prey abundance to facilitate the Newfoundland Marten population increase, there are some negative aspects to the introduction of the Southern Red-backed Vole. The Southern Red-backed Vole competes with the Meadow Vole and therefore will have an effect by decreasing the distribution and densities of the Meadow Vole,[3] which are an important prey species. The introduction of the Southern Red-backed Vole could also pull in the Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) populations which compete with the Newfoundland Marten because of a major dietary overlap therefore increasing competition for food.[3] Red Fox are also the most important natural predator of the Newfoundland Marten and with the increase in food competition will also lead to an increase in intraguild predation.[3]

Reproduction

Newfoundland Martens reach sexual maturity at 15 months, breeding once a year.[6] Behavioral interactions and patterns of scent-marking suggest that the female influences the male marking and activity.[12] Marking often happens in the same locations and is thought to facilitate social interaction.[12] The breeding season begins early July continuing until late July to August. During this time period there is an increase in scent-marking, intersexual body contact, and intrasexual female aggression.[12] Martens scent-mark with anal and abdominal scent glands that they drag over the ground and trees, as well as by spraying.[12] The scent-marking brings individuals together for mating, which includes mock wrestling.[12] The female martens seem to control the timing and duration of mating, sometimes encourage the male on some occasions.[12] The young are born in April in litter sizes of 1-5 inside dens sometimes underground, usually on steep slopes.[6] Den sites have also included rock piles, squirrel middens, and tree cavities.[4] The kits are born blind, dear, and fur-less getting weaned at about 42 days.[6] The dens are protected from April 1 to June 30.[6] Fecundity is thought to be particularly low because of the reduced diversity and abundance of prey that historically occur on the island.[6]

Population

The Newfoundland marten is genetically distinct from the American marten.[13] Populations have declined drastically since 1800's as a result of habitat loss from logging and overtrapping.[12] The population census from 1986 was at 630-875 individuals decreased to 300 animals in 1995 creating the concern that inbreeding could become a problem in the population.[2] The Newfoundland marten's population appears to be several small metapopulations that have limited interpopulation dispersal there is a large concern for the viability of the species.[14] The recent population census in 2007 estimates that the individual numbers are between 286 and 556 adults that are spread across 5 subpopulations with mean densities ranging from 0.04 to 0.08 marten per km2.[4]

Status

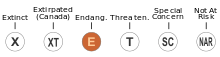

The Newfoundland marten is considered to be endangered and is protected in Canada under the Species at Risk Act (SARA), the Canada National Parks Act, and the Newfoundland and Labrador Endangered Species Act. The animal was first designated as Threatened in 1986, and was redesignated as Endangered in 1996 and 2000, with an estimated population of 300. COSEWIC re-evaluated the species in April 2007, and changed the designation to Threatened.[15]

Threats

Clear-cut harvesting techniques that are practiced throughout the boreal forest impact the Newfoundland marten directly because of habitat loss and at the scale cutting is occurring it is the greatest impact.[7] Habitat loss is not just from forest harvest, though it is the greatest, it also occurs from agricultural development, mining operations, expansion of development areas, and construction of roads and utility corridors.[4] The Newfoundland marten depends on the forested area for denning and resting sites, foraging habitat as well as breeding habitat.[4] The habitat that then follows is often a much lower quality habitat because it is second-growth forest.[7] Within this lower quality forest, martens must spend more energy to defend a larger area in order to have the resources necessary, but still have increased risk of predation and lower foraging success in these stands.[4] Clear-cut size is determined by the economic logistic constrains including road accessibility, topography and the areas of mature timber.[7] Typically cutting will harvest all merchantable timber, near 1000 ha, leaving small stands as residuals.[7] Adjacent areas are harvested during the next successive years, and adding in the new roads, the area of clear-cuts over time is very large.[7] The areas of treeless land inhibits marten dispersal, which decreases genetic variation and dispersal in areas with barriers.[2]

Historically, overtrapping had been the cause of decline for the Newfoundland marten.[13] During the mid-1800s it was documented many thousands of marten pelts were exported to the United Kingdom from communities on Newfoundland.[6] Legal trapping season for the Newfoundland marten has been closed since 1934.[4] However, accidental mortality of the Newfoundland marten in snares continues at a rate of 1.45 marten per year since 1970, which out of 300 individuals is too high as well as the possibility of unreported kill.[13] Snares set for snowshoe hares cause 92% of juvenile mortality and 58% of adult mortality in the marten.[4]

Other threats for the Newfoundland Marten also include diseases that can be spread my farmed mink or other mustelids, as well as disease from domestic animals.[4] There is also the unknown effect of the introduction of the Southern Red-backed Vole, including the potential impact of increasing predators including red fox, coyote, and raptors, all of which will kill marten and compete for food and den sites.[4]

Recovery

In 1996, a captive breeding program was started at the Salmonier Nature Park, near St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, producing litters in 1999 and 2002; this program has since ceased.[15] The attempts to breed martens in captivity have failed or produced inconsistent results to continue the program.[12] In 1999, four captive-breed martens were released to the wild near Terra Nova National Park.[5]

The remaining habitat on Newfoundland was designated as "Pine Marten Study Area" (PMSA) due to the major decline by 1973 and within this area all trapping and snaring was prohibited because it was thought to be the major cause of mortality.[14] Logging within the PMSA area continued until 1987, by which about half the forest portion was logged.[14] Outside of the PMSA, population continued to decline leading the Committee on the status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) to list on April 1986 the Newfoundland marten as threatened.[14] The Western Newfoundland Model Forest (WNMF) is not a land-holding agency but instead collaborates with provincial agencies, local governments, timber corporations and environmental groups to develop management plans for all resources within its administrative boundary which includes the PMSA area.[14]

A Recovery Plan was created by a recovery team to protect the Newfoundland marten by seven objectives including: 1) maintain and enhance existing populations and support the natural historical dispersal, 2) identify the distribution of critical and recovery habitat, 3) manage critical and recovery habitat for survival, 4) reduce incidental mortality by reducing incidental snaring and trapping, 5) continue understanding marten ecology for effective management, 6) continue population monitoring to assess recovery success, and 7) obtain stakeholder support and involvement.[4] The National Recovery Plan aimed to establish 2 discrete populations on the island with a minimum size of 350 animals each with 100 satellite animals.[13]

In order to reduce incidental mortality by snaring and trapping and habitat loss by timber harvesting critical habitat for the Newfoundland marten was placed in groups for legal protection. Therefore, 100% of the critical habitat for the marten has at least partial form of legal protection.[4] A total of 29% of critical habitat is fully protected where all forestry harvesting, traps and snares are legally prohibited.[4] The remainder of the areas have partial protection from both harvesting and trapping and snaring, as well as using the approved snaring and trapping techniques.[4] Snare mortality has also been reduced by a modified snare mechanism that was developed.[13] The modified snare is designed to exploit the behavioral differences between the hare and marten where hare tend to pull against a snare but martens tend to twist.[13] The modified snares in a controlled setting successfully retained 100% of hares and released 100% of martens tested.[13] However, this modified snare still if improperly set will reduce the effectiveness at releasing trapped marten, therefore education and training programs have begun to improve correct setting and increase participation in snare regulations.[13]

References

- ↑ "Martes americana atrata". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- 1 2 3 Kyle, C.J; C. Strobeck (2003). "Genetic homogeneity of Canadian mainland marten populations underscores the distinctiveness of Newfoundland pine martens (Martes americana atrata)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 81: 57–66. doi:10.1139/z02-223.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hearn, B.J.; J.T. Neville; W.J. Curran; D.P. Snow (2006). "First record of the Southern Red-backed Vole, Clethrionomys gapperi, in Newfoundland: implications for the endangered Newfoundland Marten, Martes americana atrata". The Canadian Field-Naturalist. 120: 50–56.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Hearn, B.; The Newfoundland Marten Recovery Team (2010). "Recovery plan for the threatened Newfoundland population of the American marten (Martes americana atrata)". Wildlife Division, Department of Environment and Conservation: iii–31. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - 1 2 "American marten Newfoundland population". Species at Risk Public Registry. Environment Canada. January 11, 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Dover, P. (Spring: 28-29). "The Newfoundland pine marten". The Probe Post. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Sturtevant, B.R.; J.A. Bissonette; J.N. Long (1996). "Temporal and spatial dynamics of boreal forest structure in western Newfoundland: silvicultural implications for marten habitat management". Forest Ecology and Management. 87: 13–25. doi:10.1016/s0378-1127(96)03837-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Gosse, J.W.; B.J. Hearn (2005). "Seasonal Diets of Newfoundland Martens, Martes americana atrata". The Canadian Field-Naturalist. 119: 43–47.

- ↑ Bissonette, J.A.; R.J. Fredrickson; B.J. Tucker (1989). "American marten: a case for landscape-level management". Transactions of the North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference. 54: 89–101.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hearn, B.J.; D.J. Harrison; A.K. Fuller; C.G. Lundrigan; W.J. Curran (2010). "Paradigm shifts in habitat ecology of threatened Newfoundland Martens". Journal of Wildlife Management. 74: 719–728. doi:10.2193/2009-138.

- ↑ Payer, D.C.; D.J. Harrison (2002). "Structural differences between forests regenerating following spruce budworm defoliation and clear-cut harvesting: implication for marten". Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 30: 1965–1972. doi:10.1139/x00-129.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Heath, J.P.; D.W. McKay; M.O. Pitcher; A.E. Storey (2001). "Changes in the reproductive behaviour of the endangered Newfoundland marten (Martes americana atrata): implications for captive breeding programs". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 79: 149–153. doi:10.1139/z00-192.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fisher, J.T.; C. Twitchell; W. Barney; E. Jenson; J. Sharpe (2005). "Utilizing behavioral biophysics to mitigate mortality of snared endangered Newfoundland marten". Journal of Wildlife Management. 69: 1743–1746. doi:10.2193/0022-541x(2005)69[1743:ubbtmm]2.0.co;2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Adair, W.A.; J.A. Bissonette (1995). "Individual-based models as a forest management tool: the Newfoundland Marten as a Case Study". Trans. 60th North American Wildlife & Natural Resources Conference. 60: 251–257.

- 1 2 "COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the American marten (Newfoundland population)". Government of Canada. Retrieved May 21, 2008.