Nihonga

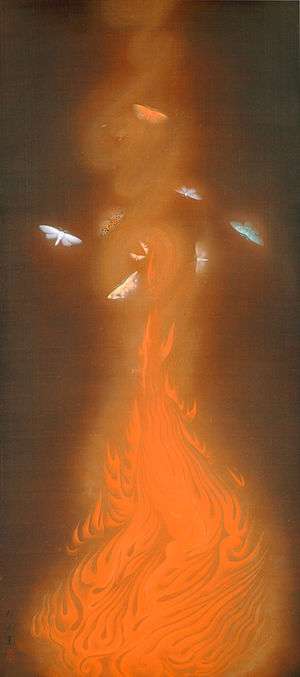

Nihonga (日本画, "Japanese-style paintings") are paintings that have been made in accordance with traditional Japanese artistic conventions, techniques and materials. While based on traditions over a thousand years old, the term was coined in the Meiji period of the Imperial Japan, to distinguish such works from Western-style paintings, or Yōga (洋画).

History

The impetus for reinvigorating traditional painting by developing a more modern Japanese style came largely from many artist/educators, which included; Shiokawa Bunrin, Kōno Bairei, Tomioka Tessai, and art critics Okakura Tenshin and Ernest Fenollosa who attempted to combat Meiji Japan's infatuation with Western culture by emphasizing to the Japanese the importance and beauty of native Japanese traditional arts. These two men played important roles in developing the curricula at major art schools, and actively encouraged and patronized artists.

Nihonga was not simply a continuation of older painting traditions. In comparison with Yamato-e the range of subjects was broadened. Moreover, stylistic and technical elements from several traditional schools, such as the Kanō-ha, Rinpa and Maruyama Ōkyo were blended together. The distinctions that had existed among schools in the Edo period were minimized.

However, in many cases Nihonga artists also adopted realistic Western painting techniques, such as perspective and shading. Because of this tendency to synthesize, although Nihonga form a distinct category within the Japanese annual Nitten exhibitions, in recent years, it has become increasingly difficult to draw a distinct separation in either techniques or materials between Nihonga and Yōga.

The artist Tenmyouya Hisashi has (b. 1966) developed a new art concept in 2001 called "Neo-Nihonga".

Development outside Japan

Nihonga has a following around the world; notable Nihonga artists who are not based in Japan are Hiroshi Senju, the Canadian artist Miyuki Tanobe, American artists Makoto Fujimura and Judith Kruger,[1] and Indian artist Madhu Jain.[2] Taiwanese artist Yiching Chen teaches workshops in Paris.[3] Judith Kruger initiated and taught the course "Nihonga: Then and Now" at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and at the Savannah, Georgia Department of Cultural Affairs.

Contemporary Nihonga has been the mainstay of New York's Dillon Gallery.[4] Key artists from the "golden age of post war Nihonga" from 1985 to 1993 based at Tokyo University of the Arts have produced global artists whose training in Nihonga has served as a foundation. Takashi Murakami, Hiroshi Senju, Norihiko Saito, Chen Wenguang, Keizaburo Okamura and Makoto Fujimura are the leading artists exhibiting globally, all coming out of the distinguished Doctorate level curriculum at Tokyo University of the Arts. Most of these artists are represented by Dillon Gallery.

Materials

Nihonga are typically executed on washi (Japanese paper) or eginu (silk), using brushes. The paintings can be either monochrome or polychrome. If monochrome, typically sumi (Chinese ink) made from soot mixed with a glue from fishbone or animal hide is used. If polychrome, the pigments are derived from natural ingredients: minerals, shells, corals, and even semi-precious stones like malachite, azurite and cinnabar. The raw materials are powdered into 16 gradations from fine to sandy grain textures. A hide glue solution, called nikawa, is used as a binder for these powdered pigments. In both cases, water is used; hence nihonga is actually a water-based medium. Gofun (powdered calcium carbonate that is made from cured oyster, clam or scallop shells) is an important material used in nihonga. Different kinds of gofun are utilized as a ground, for under-painting, and as a fine white top color.

Initially, nihonga were produced for hanging scrolls (kakemono), hand scrolls (emakimono), sliding doors (fusuma) or folding screens (byōbu). However, most are now produced on paper stretched onto wood panels, suitable for framing. Nihonga paintings do not need to be put under glass. They are archival for thousands of years.

Techniques

In monochrome Nihonga, the technique depends on the modulation of ink tones from darker through lighter to obtain a variety of shadings from near white, through grey tones to black and occasionally into greenish tones to represent trees, water, mountains or foliage. In polychrome Nihonga, great emphasis is placed on the presence or absence of outlines; typically outlines are not used for depictions of birds or plants. Occasionally, washes and layering of pigments are used to provide contrasting effects, and even more occasionally, gold or silver leaf may also be incorporated into the painting.

See also

References

- Briessen, Fritz van. The Way of the Brush: Painting Techniques of China and Japan. Tuttle (1999). ISBN 0-8048-3194-7

- Conant, Ellen P., Rimer, J. Thomas, Owyoung, Stephen. Nihonga: Transcending the Past: Japanese-Style Painting, 1868-1968. Weatherhill (1996). ISBN 0-8348-0363-1

- Setsuko Kagitani: Kagitani Setsuko Hanagashû - Flowers, Tohôshuppan, Tokyo, ISBN 978-4-88591-852-0

- Weston, Victoria. Japanese Painting and National Identity: Okakura Tenshin and His Circle. Center for Japanese Studies University of Michigan (2003). ISBN 1-929280-17-3

External links

![]() Media related to Nihonga at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nihonga at Wikimedia Commons