Norman Bethune

| Norman Bethune | |

|---|---|

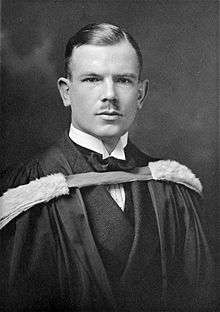

Dr. Norman Bethune (1916)[1] | |

| Born |

Henry Norman Bethune March 4, 1890 Gravenhurst, Ontario, Canada |

| Died |

November 12, 1939 (aged 49) Tang County, Hebei, China |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Education | University of Toronto |

| Known for | Developing mobile medical units, surgical instruments and a method for transporting blood for transfusions. |

|

Medical career | |

| Profession | Physician, Surgeon |

| Institutions | Royal Victoria Hospital (affiliated with McGill University) |

Henry Norman Bethune /ˈbɛθˌjuːn/ (March 4, 1890 – November 12, 1939; Chinese: 白求恩; pinyin: Bái Qiú'ēn) was a Canadian physician, medical innovator, and noted anti-fascist. Bethune came to international prominence first for his service as a frontline surgeon supporting the democratically elected Republican government during the Spanish Civil War. But it was his service with the Communist Eighth Route Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War that would earn him enduring acclaim. Dr. Bethune effectively brought modern medicine to rural China and often treated sick villagers as much as wounded soldiers. His selfless commitment made a profound impression on the Chinese people, especially CPC's leader, Mao Zedong. The chairman wrote a famous eulogy to him, which was memorized by generations of Chinese people.[2]

While Bethune was the man responsible for developing a mobile blood-transfusion service for frontline operations in the Spanish Civil War, he himself died of blood poisoning.[3]

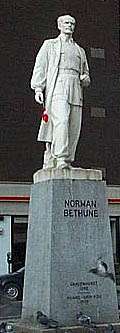

A prominent Communist and veteran of the First World War, he wrote that wars were motivated by profits, not principles.[4] Statues in his honor can be found in cities throughout China.

Family history

Dr. Norman Bethune came from a prominent Scottish Canadian family. His great-great-grandfather, the Reverend Doctor John Bethune (1751–1815), the family patriarch, established the first Presbyterian congregation in Montreal, the first five Presbyterian churches in Ontario and was one of the founders of the Presbyterian Church of Canada.

Norman Bethune’s great-grandfather, Angus Bethune (1783–1858), joined the North West Company at an early age and travelled extensively throughout the North Western territories, exploring and trading for furs. He eventually reached the Pacific at Fort Astoria, Oregon. He became chief factor of the Lake Huron district for the Hudson's Bay Company after the merger of the rival companies. Upon retirement from the HBC in 1839, he successfully ran for a post as an alderman on Toronto City Council.[5]

Norman’s grandfather, also named Norman (1822–92), was educated as a doctor at King's College, University of Toronto, and in London, England at Guy's Hospital, graduating in 1848 as a member of the Royal College of Physicians. Upon his return to Canada, he became one of the founders of the Upper Canada School of Medicine,[6] which was incorporated into Trinity College, Toronto and eventually the University of Toronto.

Bethune’s father, the Rev. Malcolm Nicolson Bethune, led an uneventful life as a small-town pastor, initially at Gravenhurst, Ontario, from 1889 to 1892. His mother was Elizabeth Ann Goodwin, an English immigrant to Canada. Both his parents were very religious. But although he was raised in a religious family, Bethune himself was an atheist.[7] Norman grew up with a "fear of being mediocre," instilled into him by his emotionally strict father and domineering mother.[8]

Early life

Norman was born in Gravenhurst, Ontario, on March 4, 1890. His birth certificate erroneously stated March 3.[9] His siblings were his sister Janet and brother Malcolm.

As a youth, Bethune attended Owen Sound Collegiate Institute in Owen Sound, Ontario, now known as Owen Sound Collegiate and Vocational Institute (OSCVI). He graduated from OSCVI in 1907. In September 1909 he enrolled at the University of Toronto. He interrupted his studies for one year in 1911 to be a volunteer laborer-teacher with Frontier College at remote lumber and mining camps throughout northern Ontario, teaching immigrant mine laborers how to read and write English.

In 1914, when World War I was declared in Europe, he once again suspended his medical studies. In a flourish of patriotism he joined the Canadian Army's No. 2 Field Ambulance to serve as a stretcher-bearer in France. He was wounded by shrapnel and spent three months recovering in an English hospital. When he had recuperated from his injuries, he returned to Toronto to complete his medical degree. He received his M.D. in 1916.[8]

Personal life

In 1917, with the war still in progress, Bethune joined the Royal Navy as a Surgeon-Lieutenant at the Chatham Hospital in England. In 1919, he began an internship specializing in children's diseases at The Hospital for Sick Children at Great Ormond Street, London. Later he went to Edinburgh, where he earned the FRCS qualification at the Royal College of Surgeons.[10] In 1920 he met Frances Penny whom he married in 1923. After a one-year “Grand Tour” of Europe, during which they spent much of her inheritance, they moved to Detroit, Michigan, where Bethune took up private practice and also took a part-time job as an instructor at the Detroit College of Medicine and Surgery.

In 1926 Bethune contracted tuberculosis. He sought treatment at the Trudeau Sanatorium in Saranac Lake, New York. At this time, Frances divorced Bethune and returned to her home in Scotland.

In the 1920s the established treatment for TB was total bed rest in a sanatorium. While convalescing Bethune read about a radical new treatment for tuberculosis called pneumothorax. This involved artificially collapsing the tubercular (diseased) lung, thus allowing it to rest and heal itself. The physicians at the Trudeau thought this procedure was too new and risky. But Bethune insisted. He had the operation performed and made a full and complete recovery.

In 1929 Bethune remarried Frances; the best man at the wedding was his friend and colleague Dr. Graham Ross. They divorced again, for the final time, in 1933.

In 1928 Bethune joined the thoracic surgical pioneer, Dr. Edward William Archibald, surgeon-in-chief of the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal, the teaching hospital affiliated with McGill University.[10] From 1928 to 1936 Bethune perfected his skills in thoracic surgery and developed or modified more than a dozen new surgical tools. His most famous instrument was the Bethune Rib Shears, which still remain in use today.[11][12] He published 14 articles describing his innovations in thoracic technique. He started his career in surgery at the Toronto General Hospital in 1921.

Political activities

Bethune became increasingly concerned with the socioeconomic aspects of disease. As a concerned doctor in Montreal during the economic depression years of the 1930s, Bethune frequently sought out the poor and gave them free medical care. He challenged his professional colleagues and agitated, without success, for the government to make radical reforms of medical care and health services in Canada.

Bethune was an early proponent of socialized medicine and formed the Montreal Group for the Security of People's Health. In 1935 Bethune travelled to the Soviet Union to observe firsthand their system of health care. During this year he became a committed Communist and joined the Communist Party of Canada. When returning from the Spanish Civil War to raise support for the Loyalist cause, he openly identified with the Communist cause.

Spanish Civil War

Shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, with the financial backing of the Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, Bethune went to Spain to offer his services to the government (Loyalist) forces. He arrived in Madrid on November 3.

Unable to find a place where he could be used as a surgeon, he seized on an idea which may have been inspired by his limited experience of administering blood transfusions as Head of Thoracic Surgery at the Sacred Heart Hospital in Montreal between 1932 and 1936. The idea was to set up a mobile blood transfusion service by which he could take blood donated by civilians in bottles to wounded soldiers near the front lines. Though Bethune's unit, the Servicio canadiense de transfusión de sangre, was not the first of its kind—a similar service had been set up in Barcelona by a Spanish haematologist, Dr. Frederic Durán-Jordà, and had been functioning since September—Bethune's Madrid-based unit covered a far wider area of operation.[13]

Bethune returned to Canada on June 6, 1937, where he went on a speaking tour to raise money and volunteers for the Spanish Civil War.

Shortly before leaving for Spain, Bethune wrote the following poem, published in the July 1937 edition of The Canadian Forum:

And this same pallid moon tonight,

Which rides so quietly, clear and high,

The mirror of our pale and troubled gaze,

Raised to a cool Canadian sky.

Above the shattered mountain tops,

Last night, rose low and wild and red,

Reflecting back from her illumined shield,

The blood bespattered faces of the dead.

To that pale disc, we raise our clenched fists,

And to those nameless dead our vows renew,

“Comrades, who fought for freedom and the future world,

Who died for us, we will remember you.”

China

In January 1938 Bethune travelled to Yan'an in the Shanbei region of Shaanxi province in China. There he joined the Chinese Communists led by Mao Zedong. The Lebanese-American doctor George Hatem, who had come to Yan'an earlier, was instrumental in helping Bethune get started at his task of organizing medical services for the front and the region.[14]

In China, Bethune performed emergency battlefield surgical operations on war casualties and established training for doctors, nurses, and orderlies.[15] He did not distinguish between casualties.[4][16]

Bethune had thoughts of medicinal disciplines and states:

Medicine, as we are practising it, is a luxury trade. We are selling bread at the price of jewels. ... Let us take the profit, the private economic profit, out of medicine, and purify our profession of rapacious individualism ... Let us say to the people not ' How much have you got?' but ' How best can we serve you?'[17][18][19]

In the summer of 1939 Bethune was appointed medical advisor to the Jin-Cha-Ji (Shanxi-Chahar-Hebei) Border Region Military District, under the direction of General Nie Rongzhen.[20]

Stationed with the Communist Party of China's Eighth Route Army in the midst of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Bethune cut his finger while operating on a soldier. Probably due to his weakened state, he contracted septicaemia (blood poisoning) and died of his wounds on November 12, 1939.[21]

His last will in China was recorded shortly before his death, reading:

Dear Commander Nie, Today I feel really bad. Probably I have to say farewell to you forever! Please send a letter to Tim Buck the General Secretary of Canadian Communist Party. Address is No.10, Wellington Street, Toronto, Canada. Please also make a copy for Committee on International Aid to China and Democratic Alliance of Canada, tell them, I am very happy here... Please give my Kodak Retina II camera to comrade Sha Fei. Norman Bethune, 04:20pm, November 11th, 1939.[22]

Legacy

Virtually unknown in his homeland during his lifetime, Bethune received international recognition when Chairman Mao Zedong of the People's Republic of China published his essay entitled In Memory of Norman Bethune (Chinese: 紀念白求恩),[23] which documented the final months of the doctor's life in China. Almost the entire Chinese population knew about the essay which had become required reading in China's elementary schools during the 1960s.[24][25] Grateful of Bethune’s altruistic help to China, the nation's normal elementary school text book still has the essay today:

Comrade Bethune’s spirit, his utter devotion to others without any thought of self, was shown in his great sense of responsibility in his work and his great warm-heartedness towards all comrades and the people. Every Communist must learn from him. ... We must all learn the spirit of absolute selflessness from him. With this spirit everyone can be very useful to the people. A man’s ability may be great or small, but if he has this spirit, he is already noble-minded and pure, a man of moral integrity and above vulgar interests, a man who is of value to the people.[26][27][28][29]

Bethune is one of the few Westerners to whom China has dedicated statues, of which many have been erected in his honour throughout the country. He is buried in the Revolutionary Martyrs' Cemetery, Shijiazhuang, Hebei Province, China, where his tomb and memorial hall lie opposite the tomb of Dwarkanath Kotnis, an Indian doctor also honoured for his humanitarian contribution to the Chinese. One of the three honoured in this memorial is the hero of the Academy Award–winning film, Chariots of Fire, Reverend Eric Liddell of Scotland. He died while incarcerated in a Japanese prisoner of war camp in Shandong Province.

Elsewhere in China, Norman Bethune University of Medical Sciences, in Changchun city, Jilin province, was one of the eleven national medical universities directly subordinated to Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China. The predecessor of this University was the Hygiene School of Jin-Cha-Ji Military Region of the Eighth Route Army(八路军晋察冀军区卫生学校 in Chinese) founded in 1939 by Bethune's advocacy. The school developed with Bethune Hygiene School (Feb 16, 1940), Bethune Medical School (Jan 1946), Bethune Medical University (June 1946), Medical University of North China(1948), First Military Medical University(1951 in Tianjin), moved to Changchun in 1954, Medical College of Changchun(July 1958),Medical University of Jilin(June 1959), Norman Bethune University of Medical Sciences(March 1978), merged into Jilin University as Norman Bethune Health Science Center of Jilin University in 2000. There are at least three dedicated statues of Bethune in this university: in the west square of College of Basic Medicine, in the Second Affiliated Hospital and in the Third Affiliated Hospital.

He is also commemorated at three institutions in Shijiazhuang - Bethune Military Medical College, Bethune Specialized Medical College and Bethune International Peace Hospital. In Canada, Norman Bethune College at York University, and Dr. Norman Bethune Collegiate Institute (a secondary school) in Scarborough, Ontario, are named after him.

The Government of Canada purchased in 1973 the manse in which he was born in Gravenhurst following the visit of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to China. The previous year, Dr. Bethune had been declared a Person of National Historic Significance. In 1976, the restored building was opened to the public as Bethune Memorial House. In 2012, the Government of Canada opened a new visitor centre, to enhance the experience of visitors to the site.[30] The house is operated as a National Historic Site of Canada by Parks Canada.

In March 1990, to commemorate the centenary of his birth, Canada and China each issued two postage stamps of the same design in his honour.

The Norman Bethune Medal is the highest medical honour in China, bestowed by the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Personnel of China, to recognize an individual's outstanding contribution, heroic spirit and great humanitarianism in the medical field. The Norman Bethune Medal was established in 1991. Biannually, one to seven medical personnel in China received this award.[31]

In 1998, Bethune was inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame located in London, Ontario.

In August 2000, then-Governor General Adrienne Clarkson, who is of Chinese birth, visited Gravenhurst and unveiled a bronze statue of him erected by the town. It stands in front of the Opera House on the town's main street, Muskoka Road.

On February 7, 2006, the city of Málaga, Spain, opened the Walk of Canadians in his memory. This avenue, which runs parallel to the beach "Crow Rock" direction to Almeria, paid tribute to the solidarity action of Dr. Norman Bethune and his colleagues who helped the population of Málaga during the Spanish Civil War. During the ceremony, a commemorative plaque was unveiled with the inscription: "Walk of Canadians - In memory of aid from the people of Canada at the hands of Norman Bethune, provided to the refugees of Málaga in February 1937." The ceremony also included a planting of an olive tree and a maple tree representative of Spain and Canada, symbols of friendship between the two peoples.

The city of Montreal, Quebec, has created a public square and erected a statue of him in his honor, located near the Guy-Concordia Metro station.[32]

A celebration was scheduled for October 13, 2010, in honor of the 40th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Canada and the People’s Republic of China and on the occasion of the opening of the exhibition “Life of Norman Bethune.”

The 2007 Harbin International Ice and Snow Sculpture Festival featured as its central theme a memorial to Bethune.

Bethune in film and literature

Doctor Bethune (Chinese: 白求恩大夫; pinyin: Bái Qiú'ēn Dàifu), was made in 1964; Gerald Tannebaum, an American humanitarian, played Bethune.

Bethune was the subject of a 1964 National Film Board of Canada documentary Bethune, directed by Donald Brittain. The film includes interviews with many people close to Bethune, including his biographer Ted Allan.[33]

Donald Sutherland played Bethune in the 1974–75 television show Witness to Yesterday hosted by Patrick Watson, produced by Arthur Veronka, and sponsored by Shell Canada Limited.

Sutherland's portrayal of Bethune was eerily compelling and (likely) led to him playing Bethune in two biographical films: Bethune (1977),[34] made for television on a low budget, and Bethune: The Making of a Hero (1990).[35] The latter, based on a 1952 book The Scalpel, The Sword; The Story Of Doctor Norman Bethune by Ted Allan and Sydney Gordon,[36] was a co-production of Telefilm Canada, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, FR3 TV France and China Film Co-production.

In the CBC's The Greatest Canadian program in 2004, he was voted the 26th Greatest Canadian by viewers.

In 2006 China Central Television produced a 20-part drama series, Norman Bethune (诺尔曼·白求恩), documenting his life, which with a budget of yuan 30 million (US$3.75 million) was the most expensive Chinese TV series to date. The series is directed by Yang Yang and stars Canadian actor Trevor Hayes.[37][38]

The 2006 novel The Communist's Daughter, by Dennis Bock, is a fictionalized account of Bethune's life.[39]

Adrienne Clarkson, a Chinese-Canadian and former Governor General, wrote a biography of Bethune for Penguin Canada's best-selling Extraordinary Canadians series and tells his story in the companion documentary 'Adrienne Clarkson on Norman Bethune' on YouTube.

The Bethune biographer, Roderick Stewart, has produced five books on Norman Bethune, including "Bethune," (1973), "The Canadians: Norman Bethune," (1974), "The Mind of Norman Bethune," (1990). In 2011, he co-authored with Sharon Stewart, "Phoenix: The Life of Norman Bethune." a book which Canadian author Michael Bliss, in his review in the "Globe and Mail," said, "should become the definitive basis for all serious discussion of Bethune."[40] In 2014 "Bethune in Spain", written by Stewart and co-author Jesus Majada, was published by Oberon Press.

The television miniseries Canada: A People's History, by CBC Television, briefly mentioned Bethune's story during the episode describing Canadians in the Spanish Civil War.

When the CBC decided to produce a film version of Rod Langley's 1973 play "Bethune", they offered the leading role to Donald Sutherland. After accepting, Sutherland persuaded the CBC to allow Thomas Rickman to rework the Langley script. Rickman's script, based on Roderick Stewart's 1973 biography "Bethune", was used in "Bethune", the 1977 CBC film production.

The character Jerome Martell in Hugh MacLennan's novel The Watch That Ends the Night is generally thought to have been inspired by Bethune, a claim MacLennan denied, though they were known to one another and MacLennan based much of his writing off his own life experiences. In , Canadian rock group The Tragically Hip wrote their 1992 hit Courage (for Hugh MacLennan) in tribute to the author and in reference to The Watch in particular. The song's refrain 'Courage, it couldn't have come at a worse time' is a reference to the novel's climax, in which the 'Bethunian' qualities of Jerome Martell are at their peak.

Saskatchewan playwright Ken Mitchell's one-man play, Gone The Burning Sun (1991), is about Bethune's life and time in China.

The Secret History of the Intrepids, by D.K. Latta, is an Alternate History fantasy story imagining Norman Bethune, William Stephenson, Grey Owl and others as 1940s super heroes. It was published in the 2013 anthology, Masked Mosaic: Canadian Super Stories.

The book "Dr. Bethune's Angel - The Life of Kathleen Hall" by Tom Newnham (published 2002) tells the story of the work of the two in China. Published in New Zealand; Hall was a New Zealander.

See also

- John Rabe

- Edgar Snow

- Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham

- Edward H. Hume

- Dwarkanath Kotnis

- Leonora King, a Canadian doctor honoured by the Qing Empire for her work during the First Sino-Japanese War

- Bethune Memorial House

- Gregor Robertson, Mayor of Vancouver and distant relative of Bethune

- Jean Ewen, A Canadian nurse who worked with Bethune in China

References

- ↑ Norman Bethune - graduation photo. Library and Archives Canada. MIKAN No. 3224423

- ↑ http://www.extraordinarycanadians.com/pdf/clarkson.pdf

- ↑ "Henry Norman Bethune Biography". Encyclopedia of World Biography. Thomson Corporation. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 Bethune, Norman (1939). "Wounds". The Marxist-Leninist. Retrieved August 5, 2015.

- ↑ Russell, Hilary (1985). "Bethune, Angus". In Halpenny, Francess G. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. VIII (1851–1860) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ MacDougall, Heather (1990). "Bethune, Norman". In Halpenny, Francess G. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. XII (1891–1900) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Bethune, Norman (1998). Hannant, Larry, ed. The Politics of Passion: Norman Bethune's Writing and Art. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-0907-4. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

Bethune was a communist and an atheist with a healthy contempt for his evangelical father.

- 1 2 McEnaney, Marjorie (September 13, 1964). "The early years of Norman Bethune". CBC Digital Archives. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Stewart, Roderick; Stewart, Sharon. Phoenix: The Life of Norman Bethune. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-3819-1., p. 7

- 1 2 MacLean, Lloyd D.; Entin, Martin A. (2000). "Norman Bethune and Edward Archibald: sung and unsung heroes" (PDF). Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 70 (5): 1746–1752. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(00)02043-9. PMID 11093539. Retrieved August 5, 2015.

- ↑ Canadian Medicine: Mobile Blood Banks at www.mta.ca Archived March 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The Innovative Healer". Norman Bethune 1890 - 1939. Retrieved August 5, 2015.

- ↑ Stewart & Stewart (2011), pp.163-176

- ↑ Porter, Edgar A (1997). The People's Doctor: George Hatem and China's Revolution. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 115–118. ISBN 0-8248-1905-5.

- ↑ Alexander, C A, New York-tidewater chapters' history of military medicine award: The military odyssey of Norman Bethune, Military Medicine, April 1999

- ↑ Taylor, Robert (1986). America's Magic Mountain. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-37905-9.

- ↑ "Patients, Practitioners, & Medical Care". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 120 (12): 1500. 1979. PMC 1704189

.

. - ↑ Patterson, Robert, MD (November 1, 1989). "Norman Bethune: His Contributions to Medicine and CMAJ" (PDF). Canadian Medical Association Journal. 141 (9): 947–953. Retrieved August 5, 2015.

- ↑ Allan, Ted; Gordon, Sydney. The Story of Doctor Norman Bethune. p. 130.

- ↑ Porter (1997), p. 122-123.

- ↑ Russell, Hilary (August 8, 2008). "Norman Bethune". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada. Retrieved August 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Photographic history: Bethune's camera was given to comrade Sha Fei". Zhao Junyi (in Chinese). vision.xitek.com. 2010-09-08.

- ↑ Mao Zedong. "In Memory of Norman Bethune".

- ↑ "Norman Bethune". ChinesePosters.net. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Three Constantly Read Articles". ChinesePosters.net. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ In Memory of Norman Bethune, December 21, 1939. Selected Works, Vol. II pp. 337-38. Quoted in the Quotations of Chairman Mao Zedong, Chapter 17: Serving the People.

- ↑ "In Memory of Norman Bethune". GoodReads.com. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Chinese still cherish memory of Norman Bethune". People's Daily Online. December 22, 2004. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ Jingqing Yang (November 3, 2008). Serve the People: Ethics of Medicine in China (PDF). EASP 5th Conference: Welfare Reform in East Asia. National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan: East Asia Social Policy. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ "New Visitor Centre at Bethune Memorial House Receives a Hero's Welcome" (Press release). Government of Canada. July 11, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ "白求恩奖章" [Bethune Medal]. Xinhua News Agency (in Chinese).

- ↑ Hustak, Allan (December 3, 2007). "Statue of Bethune getting new home". The Gazette (Montreal). Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ Brittain, Donald (1964). Bethune. National Film Board of Canada. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Bethune (1977)". IMDB.com. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Bethune: The Making of a Hero (1990)". IMDB.com. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ Allan, Ted; Gordon, Sydney (1989). The Scalpel, the Sword: The Story of Dr. Norman Bethune (Revised ed.). McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 0-7710-0729-9.

- ↑ Xinhua (August 31, 2006). "Sixty-seven years on, Canadian idealist moves China again". People's Daily Online. Retrieved September 1, 2006.

- ↑ "诺尔曼·白求恩" [Norman Bethune]. baike.com (in Chinese). Retrieved August 6, 2015.

Descriptions of all 20 episodes with photographs.

- ↑ Bock, Dennis (2007) [2006]. "The Communist's Daughter". New York: Alfred A. Kopf. ISBN 978-1-4000-4462-7.

- ↑ Bliss, Michael (July 1, 2011). "Phoenix: The Life of Norman Bethune Reviewed by Michael Bliss". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- "Norman Bethune". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. 1979–2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Norman Bethune. |

- Norman Bethune Collection at the Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University.

- Norman Bethune Memorial Sites map

- In Memory of Norman Bethune by Mao Zedong

- Bethune Memorial House National Historic Site of Canada

- Chinese Posters of Bethune

- Photographs of a five by sixty foot mural drawn by Bethune while a patient at the Trudeau Sanatorium in 1927

- Bethune Institute

- Bethune Institute for Anti-Fascist Studies at the Wayback Machine (archived April 9, 2007).

- CBC Digital Archives - 'Comrade' Bethune: A Controversial Hero

- International surgery: definition, principles and Canadian Practice

- Rodríguez-Solás, D. "Remembered and Recovered: Bethune and The Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit in Málaga, 1937". Revista Canadiense de Estudios Hispánicos. 36.1 (2011): 83-100. full text

- Patterson, R. "Norman Bethune: his contributions to medicine and to CMAJ". CMAJ. November 1, 1989, 141 (9): 947–953. full text

- Watch the National Film Board of Canada documentary Bethune

- Gerd Hartmann: Humanist statt Held (German: "Humanist rather than hero").

- Bethune Memorial Route; Map of locations in North America associated with Dr. Bethune

- China's Canadian hero, Toronto Globe and Mail, book review of recent Bethune biography by Adrienne Clarkson.