Nucleation

Nucleation is the first step in the formation of either a new thermodynamic phase or a new structure via self-assembly or self-organization. Nucleation is typically defined to be the process that determines how long an observer has to wait before the new phase or self-organized structure appears. Nucleation is often found to be very sensitive to impurities in the system. Because of this, it is often important to distinguish between heterogeneous nucleation and homogeneous nucleation. Heterogeneous nucleation occurs at nucleation sites on surfaces in the system.[1] Homogeneous nucleation occurs away from a surface.

Characteristics

_from_a_metastable_phase_(white)_in_the_Ising_model.ogg.jpg)

Nucleation is usually a stochastic process, so even in two identical systems nucleation will occur at different times.[1][2][3] This behaviour is similar to radioactive decay. A common mechanism is illustrated in the animation to the right. This shows nucleation of a new phase (shown in red) in an existing phase (white). In the existing phase microscopic fluctuations of the red phase appear and decay continuously, until an unusually large fluctuation of the new red phase is so large it is more favourable for it to grow than to shrink back to nothing. This nucleus of the red phase then grows and converts the system to this phase. The standard theory that describes this behaviour for the nucleation of a new thermodynamic phase is called classical nucleation theory.

For nucleation of a new thermodynamic phase, such as the formation of ice in water below 0 °C, if the system is not evolving with time and nucleation occurs in one step, then the probability that nucleation has not occurred should undergo exponential decay as seen in radioactive decay. This is seen for example in the nucleation of ice in supercooled small water droplets.[4] The decay rate of the exponential gives the nucleation rate. Classical nucleation theory is a widely used approximate theory for estimating these rates, and how they vary with variables such as temperature. It correctly predicts that the time you have to wait for nucleation decreases extremely rapidly when supersaturated.[1][2]

It is not just new phases such as liquids and crystals that form via nucleation followed by growth. The self-assembly process that forms objects like the amyloid aggregates associated with Alzheimer's disease also starts with nucleation.[5] Energy consuming self-organising systems such as the microtubules in cells also show nucleation and growth.

Examples

- Clouds form when wet air cools (often because the air is rising) and many small water droplets nucleate from the supersaturated air.[1] The amount of water vapor that air can carry decreases with lower temperatures. The excess vapor begins to nucleate and form small water droplets which form a cloud. Nucleation of the droplets of liquid water is heterogeneous, occurring on particles referred to as cloud condensation nuclei. Cloud seeding is the process of adding artificial condensation nuclei to quicken the formation of clouds.

- Nucleation is the first step in crystallisation, so it determines if a crystal can form. Frequently crystals do not form even when they are thermodynamically the favored state. For example, small droplets of very pure water can remain liquid down to below -30 °C although ice is the stable state below 0 °C.[1]

- Bubbles of carbon dioxide nucleate shortly after the pressure is released from a container of carbonated liquid. Nucleation often occurs more easily at a pre-existing interface (heterogeneous nucleation), as happens on boiling chips and string used to make rock candy.

- Nucleation in boiling can occur in the bulk liquid if the pressure is reduced so that the liquid becomes superheated with respect to the pressure-dependent boiling point. More often, nucleation occurs on the heating surface, at nucleation sites. Typically, nucleation sites are tiny crevices where free gas-liquid surface is maintained or spots on the heating surface with lower wetting properties. Substantial superheating of a liquid can be achieved after the liquid is de-gassed and if the heating surfaces are clean, smooth and made of materials well wetted by the liquid.

- Some champagne stirrers operate by providing many nucleation sites via high surface area and sharp corners, speeding the release of bubbles and removing carbonation from the wine.

- Microtubule nucleation is the nucleation of microtubules, large rod-like structures found in eukaryote cells. This nucleation is not of a thermodynamic phase, and like other aspects of microtubule dynamics, it is an energy consuming process.

- The Diet Coke and Mentos eruption is another example. The surface of Mentos candy provides nucleation sites for the formation of carbon dioxide bubbles from carbonated soda.

Heterogeneous

Heterogeneous nucleation, nucleation with the nucleus at a surface, is much more common than homogeneous nucleation.[1][3] Heterogeneous nucleation is typically understood to be much faster than homogeneous nucleation using classical nucleation theory. This predicts that the nucleation slows exponentially with the height of a free energy barrier ΔG*. This barrier comes from the free energy penalty of forming the surface of the growing nucleus. For homogeneous nucleation the nucleus is approximated by a sphere but as we can see in the schematic of macroscopic droplets to the right, droplets on surfaces are not complete spheres and so the area of the interface between the droplet and the surrounding fluid is less than a sphere's . This reduction in surface area of the nucleus reduces the height of the barrier to nucleation and so speeds nucleation up exponentially.[2]

Nucleation can also start at the surface of a liquid. For example, computer simulations of gold nanoparticles show that the crystal phase nucleates at the liquid gold surface.[6]

Computer simulation studies of simple models

Classical nucleation theory makes a number of assumptions, for example it treats a microscopic nucleus as if it is a macroscopic droplet with a well defined surface whose free energy is estimated using an equilibrium property: the interfacial tension σ. For a nucleus that may be only of order ten molecules across it is not always clear that we can treat something so small as a volume plus a surface. Also nucleation is an inherently out of thermodynamic equilibrium phenomenon so it is not always obvious that its rate can be estimated using equilibrium properties.

However, modern computers are powerful enough to calculate essentially exact nucleation rates for simple models. These have been compared with the classical theory, for example for the case of nucleation of the crystal phase in the model of hard spheres. This is a model of perfectly hard spheres in thermal motion, and is a simple model of some colloids. For the crystallization of hard spheres the classical theory is a very reasonable approximate theory.[7] So for the simple models we can study classical nucleation theory works quite well, but we do not know if it works equally well for say complex molecules crystallising out of solution.

The spinodal region

Phase transition processes can also be explained in terms of spinodal decomposition, where phase separation is delayed until the system enters the unstable region where a small perturbation in composition leads to a decrease in energy and, thus, spontaneous growth of the perturbation.[8] This region of a phase diagram is known as the spinodal region and the phase separation process is known as spinodal decomposition and may be governed by the Cahn–Hilliard equation.

Experiments on the nucleation of crystals

It is typically difficult to experimentally study nucleation. The nucleus is microscopic and thus too small to be directly observed. In large liquid volumes there are typically multiple nucleation events and it is difficult to disentangle the effects of nucleation from those of growth of the nucleated phase. These problems can be overcome by working with small droplets. As nucleation is stochastic, many droplets are needed so that statistics for the nucleation events can be obtained.

.png)

To the right is shown an example set of nucleation data. It is for the nucleation at constant temperature and hence supersaturation of the crystal phase in small droplets of supercooled liquid tin; this is the work of Pound and La Mer.[9]

Nucleation occurs in different droplets at different times, hence the fraction is not a simple step function that drops sharply from one to zero at one particular time. The red curve is a fit of a Gompertz function to the data. This is a simplified version of the model Pound and La Mer used to model their data.[9] The model assumes that nucleation occurs due to impurity particles in the liquid tin droplets, and it makes the simplifying assumption that all impurity particles produce nucleation at the same rate. It also assumes that these particles are Poisson distributed among the liquid tin droplets. The fit values are that the nucleation rate due to a single impurity particle is 0.02/s, and the average number of impurity particles per droplet is 1.2. Note that about 30% of the tin droplets never freeze; the data plateaus at a fraction of about 0.3. Within the model this is assumed to be because, by chance, these droplets do not have even one impurity particle and so there is no heterogeneous nucleation. Homogeneous nucleation is assumed to be negligible on the timescale of this experiment. The remaining droplets freeze in a stochastic way, at rates 0.02/s if they have one impurity particle, 0.04/s if they have two, and so on.

This data is just one example but it does illustrate common features of the nucleation of crystals in that there is clear evidence for heterogeneous nucleation, and that nucleation is clearly stochastic.

Ice

The freezing of small water droplets to ice is an important process, in particular in the formation and dynamics of clouds.[1] Water (at atmospheric pressure) does not freeze at 0 C, but at temperatures that tend to decrease as the volume of the water decreases and as the water impurity increases.[1]

Thus small droplets of water, as found in clouds, may remain liquid far below 0 C.

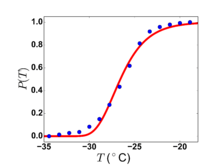

An example of experimental data on the freezing of small water droplets is shown at the right. The plot shows the fraction of a large set of water droplets, that are still liquid water, i.e., have not yet frozen, as a function of temperature. Note that the highest temperature at which any of the droplets freezes is close to -19 C, while the last droplet to freeze does so at almost -35 C. The data is from work by Dorsch and Hacker.[10]

Nucleation of a new phase that does not rely on the new phase already being present, either because it is the very first nucleus of that phase to form, or because the nucleus forms far from any pre-existing piece of the new phase. Particularly in the study of crystallisation, secondary nucleation can be important. This is the formation of nuclei of a new crystal directly caused by pre-existing crystals [11] For example, if the crystals are in a solution and the system is subject to shearing forces, small crystal nuclei could be sheared off a growing crystal, thus increasing the number of crystals in the system. So both primary and secondary nucleation increase the number of crystals in the system but their mechanisms are very different, and secondary nucleation relies on crystals already being present.

Modern technology

Nucleation is a topic of wide interest in many scientific studies and technological processes.[12] It is used heavily in the chemical industry for cases such as in the preparation of metallic ultradispersed powders that can serve as catalysts. For example, platinum deposited onto TiO2 nanoparticles catalyses the liberation of hydrogen from water.[13] It is an important factor in the semiconductor industry, as the gap width in semiconductors is influenced by the size of metal nanoclusters.[14] As another example, understanding calcium carbonate nucleation could help scientists control its formation to keep carbon dioxide from getting into the atmosphere.[15]

Instruments such as the bubble chamber and the cloud chamber rely on nucleation.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 H. R. Pruppacher and J. D. Klett, Microphysics of Clouds and Precipitation, Kluwer (1997).

- 1 2 3 Sear, R.P. (2007). "Nucleation: theory and applications to protein solutions and colloidal suspensions" (PDF). J. Physics Cond. Matt. 19 (3): 033101. Bibcode:2007JPCM...19c3101S. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/19/3/033101.

- 1 2 Sear, Richard P. (2014). "Quantitative Studies of Crystal Nucleation at Constant Supersaturation: Experimental Data and Models". CrystEngComm. 16 (29): 6506. doi:10.1039/C4CE00344F.

- ↑ Duft, D.; Leisner (2004). "Laboratory evidence for volume-dominated nucleation of ice in supercooled water microdroplets". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 4 (7): 1997. doi:10.5194/acp-4-1997-2004.

- ↑ Gillam, J.E.; MacPhee, C.E. (2013). "Modelling amyloid fibril formation kinetics: mechanisms of nucleation and growth". J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 25 (37): 373101. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/25/37/373101.

- ↑ Mendez-Villuendas, Eduardo; Bowles, Richard (2007). "Surface Nucleation in the Freezing of Gold Nanoparticles". Physical Review Letters. 98 (18): 185503. arXiv:cond-mat/0702605

. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..98r5503M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.185503. PMID 17501584.

. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..98r5503M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.185503. PMID 17501584. - ↑ Auer, S.; D. Frenkel (2004). "Numerical prediction of absolute crystallization rates in hard-sphere colloids". J. Chem. Phys. 120 (6): 3015. Bibcode:2004JChPh.120.3015A. doi:10.1063/1.1638740.

- ↑ Mendez-Villuendas, Eduardo; Saika-Voivod, Ivan; Bowles, Richard K. (2007). "A limit of stability in supercooled liquid clusters". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 127 (15): 154703. Bibcode:2007JChPh.127o4703M. doi:10.1063/1.2779875. PMID 17949187.

- 1 2 Pound, Guy M.; V. K. La Mer (1952). "Kinetics of Crystalline Nucleus Formation in Supercooled Liquid Tin". J. American Chemical Society. 74 (9): 2323. doi:10.1021/ja01129a044.

- ↑ Dorsch, Robert G; Hacker, Paul T (1950). "Photomicrographic Investigation of Spontaneous Freezing Temperatures of Supercooled Water Droplets". NACA Technical Note. 2142.

- ↑ Botsaris, GD (1976). Mullin, J, ed. Secondary Nucleation — A Review in Industrial Crystallisation. Springer. pp. 3–22.

- ↑ K. F. Kelton of Washington University in St. Louis, USA and A. L. Greer of University of Cambridge, UK (2010) Nucleation in Condensed Matter: Applications in Materials and Biology (Elsevier Science & Technology, Amsterdam) link.

- ↑ Palmans, Roger; Frank, Arthur J. (1991). "A molecular water-reduction catalyst: Surface derivatization of titania colloids and suspensions with a platinum complex". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 95 (23): 9438. doi:10.1021/j100176a075.

- ↑ Rajh, Tijana; Micic, Olga I.; Nozik, Arthur J. (1993). "Synthesis and characterization of surface-modified colloidal cadmium telluride quantum dots". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 97 (46): 11999. doi:10.1021/j100148a026.

- ↑ Nielsen, Michael; Aloni, Shaul; De Yoreo, James (September 4, 2014). "In Situ TEM Imaging of CaCO3 Nucleation Reveals Coexistence of Direct and Indirect Pathways". Science. 345 (6201): 1158–1162. doi:10.1126/science.1254051. PMID 25190792.