Oberkommando der Wehrmacht

| Oberkommando der Wehrmacht | |

|---|---|

|

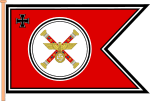

Command flag of the Chief of the OKW with the rank of Generalfeldmarschall (1941–1945) | |

| Active | 4 February 1938 – 8 May 1945 |

| Country |

|

| Branch | Wehrmacht |

| Role | German General Staff |

| Headquarters | Wünsdorf, near Zossen |

| Engagements | World War II in Europe |

| Commanders | |

| Chief of the OKW | Wilhelm Keitel |

The Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW, "Supreme Command of the Armed Forces") was part of the command structure of the Wehrmacht (armed forces) of Nazi Germany during World War II. Created in 1938, the OKW had nominal oversight over the German Army, the Kriegsmarine (German navy) and the Luftwaffe (German air force).

Rivalry with the armed services branch commands, mainly with the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH), prevented the OKW from becoming a unified German General Staff in an effective chain of command. However, it did coordinate operations between the three services. During the war, the OKW, subordinate to Adolf Hitler as Supreme Commander of the Wehrmacht, acquired more and more operational powers. By 1942, OKW had responsibility for all theaters except for the Eastern Front against the Soviet Union. Hitler manipulated the bipolar system to keep ultimate decisions in his own hands.[1]

Genesis

The OKW was established by decree of 4 February 1938 on the occasion of the Blomberg-Fritsch Affair, which had led to the dismissal of Reich War Minister and Commander-in-chief of the Wehrmacht, Generalfeldmarschall Werner von Blomberg. Hitler took the chance to get rid of his critics within the armed forces. The Reich War Ministry was dissolved and replaced with the OKW led by devoted General Wilhelm Keitel in the rank of a Reich Minister, with Alfred Jodl as Chief of the Operations Staff. Nevertheless, all Supreme Commanders of the armed service branches, like OKH Chief General Walther von Brauchitsch, had direct access to Hitler and were able to circumvent Keitel's command. The appointments made to the OKW and the motive behind the reorganization are commonly thought to be Hitler's desire to consolidate power and authority around his position as Führer and Reich Chancellor (Führer und Reichskanzler), to the detriment of the military leadership of the Wehrmacht.

Organization

By June 1938, the OKW comprised four departments:

- Wehrmacht-Führungsamt (WFA, renamed Wehrmachtführungsstab (Wfst) in August 1940) - operational orders. Chief: Colonel-General Alfred Jodl, 1 September 1939 - 8 May 1945

- Abteilung Landesverteidigungsführungsamt (WFA/L) a subdepartment through which all details of operational planning were worked out, and from which all operational orders were communicated to the OKW. Chief: Major General Walter Warlimont, 1 September 1939 - 6 September 1944; Major General Horst Freiherr Treusch von Buttlar-Brandenfels, 6 September 1944 - 30 November 1944; General August Winter, 1 December 1944 - 23 April 1945

- Abteilung Wehrmachtpropaganda - propaganda troops. Chief: Major General Hasso von Wedel, 1 September 1939 - 8 May 1945

- Heeresstab - army staff. Chief: General Walther Buhle, 15 February 1942 - 8 May 1945

- Inspekteur der Wehrmachtnachrichtenverbände - Chief of Staff, Wehrmacht signal corps

- Amt Ausland/Abwehr - foreign intelligence.[2] Chief: Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, 1 September 1939 - 12 February 1944; Colonel Georg Hansen, 13 February 1944 - 1 June 1944; SS-Brigadeführer Walter Schellenberg, 1 June 1944 - 4 May 1945; SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny, 5–8 May 1945

- Chief of Staff

- Zentralabteilung - central department. Chief: Major General Hans Oster, 1 September 1939 - January 1944

- Abteilung Ausland - foreign

- Gruppe I: Außen- und Wehrpolitik - foreign and defence policy

- Gruppe II: Beziehung zu fremden Wehrmächten - relations with foreign militaries

- Gruppe III: Fremde Wehrmachten, Meldesammelstelle des OKW - foreign militaries

- Gruppe IV: Etappenorganisation der Kriegsmarine

- Gruppe V: Auslandspresse - foreign media

- Gruppe VI: Militärische Untersuchungsstelle für Kriegsvölkerrecht - research service for international laws of war

- Gruppe VII: Kolonialfragen - colonial matters

- Gruppe VIII: Wehrauswertung - defence analysis

- Abteilung Nachrichtenbeschaffung - intelligence. Chief: Colonel Hans Piepenbrock, 1 September 1939 - March 1943; Colonel Georg Hansen, March 1943 - February 1944

- Gruppe H: Geheimer Meldedienst Heer - army intelligence service

- Gruppe M: Geheimer Meldedienst Marine - naval intelligence service

- Gruppe L: Geheimer Meldedienst Luftwaffe - air intelligence service

- Gruppe G: Technische Arbeitsmittel - technical equipment

- Gruppe wi: Geheimer Meldedienst Wirtschaft - economic intelligence service

- Gruppe P: Presseauswertung - media analysis

- Gruppe i: Funknetz Abwehr Funkstelle - radio communications

- Abteilung Sonderdienst - special service. Chief: Colonel Erwin von Lahousen, 1 September 1939 - July 1943; Colonel Wessel Freytag von Loringhoven, July 1943 - June 1944

- Gruppe I: Minderheiten - minorities

- Gruppe II: Sondermaßnahmen - special measures

- Abteilung Abwehr - counter-intelligence.

- Führungsgruppe W: Abwehr in der Wehrmacht - counter-intelligence in the military

- Gruppe Wi: Abwehr Wirtschaft - economic counter-intelligence

- Gruppe C: Abwehr Inland - inland counter-intelligence

- Gruppe F: Abwehr Ausland - foreign counter-intelligence

- Gruppe D: Sonderdienst - special service

- Gruppe S: Sabotageabwehr - counter-sabotage

- Gruppe G: Gutachten - evaluation

- Gruppe Z: Zentralarchiv - central archives

- Auslands(telegramm)prüfstelle - foreign communications

- Gruppe I: Sortierung - sorting

- Gruppe II: Chemische Untersuchung - chemical testing

- Gruppe III: Privatbriefe - private mail

- Gruppe IV: Handelsbriefe - commercial mail

- Gruppe V: Feldpostbriefe - military mail

- Gruppe VI: Kriegsgefangenenbriefe - POWs' mail

- Gruppe VII: Zentralkartei - central register

- Gruppe VIII: Auswertung - analysis

- Gruppe IX: Kriegsgefangenen-Brief-Auswertung - analysis of POWs' mail

- Wirtschafts und Rüstungsamt - supply matters [3]

- Amtsgruppe Allgemeine Wehrmachtsangelegenheiten - miscellaneous matters.

- Abteilung Inland - inland

- Allgemeine Abteilung - general

- Wehrmachtsfürsorge- und versorgungsabteilung - supplies

- Wehrmachtsfachschulunterricht - education

- Wissenschaft - science

- Wehrmachtsverwaltungsabteilung - administration

- General zu besonderen Verfügung für Kriegsgefangenenwesen - prisoners of war

- Abteilung Wehrmachtverlustwesen (WVW) - casualties

- Wehrmachtauskunftstelle für Kriegerverluste und Kriegsgefangene (WaSt) - information centre for war casualties and prisoners of war

The WFA replaced the Wehrmachtsamt (Armed Forces Office) which had existed between 1935 and 1938 within the Reich War Ministry, headed by General Wilhelm Keitel. Hitler promoted Keitel to Chief of the OKW (Chef des OKW), i.e. Chief of the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces. As head of the WFA, Keitel appointed Max von Viebahn although after two months he was removed from command, and this post was not refilled until the promotion of Alfred Jodl. To replace Jodl at Abteilung Landesverteidigungsführungsamt (WFA/L), Walther Warlimont was appointed.[4] In December 1941 further changes took place with Abteilung Landesverteidigungsführungsamt (WFA/L) being merged into the Wehrmacht-Führungsamt and losing its role as a subordinate organization. These changes were largely cosmetic however as key staff remained in post and continued to fulfill the same duties.

The OKW directed the operations of the German Armed Forces during World War II. The OKW was almost always represented at daily situation conferences (Lagevorträge) by Jodl, Keitel, and the officer serving as Hitler's adjutant. During these conferences situation reports prepared by the head of WFA/L would be delivered to Hitler and then discussed. Following these discussions, Hitler would issue further operational orders. These orders were then relayed back to WFA/L by Jodl along with the minutes of the meeting. These would then be converted into orders for issuance to the appropriate commanders.

Operation

Officially, the OKW served as the military general staff for the Third Reich, coordinating the efforts of the Army, Navy, and Air Force (Heer, Kriegsmarine, and Luftwaffe). In practice, the OKW acted as Hitler's personal military staff, translating his ideas into military orders, and issuing them to the three services while having little control over them. However, as the war progressed the OKW found itself exercising increasing amounts of direct command authority over military units, particularly in the West. This created a situation such that by 1942 the OKW held the de facto command of Western forces while the Army High Command (Oberkommando des Heeres, OKH) exercised de facto command of the Eastern Front. It was not until 28 April 1945 (two days before his suicide) that Hitler placed OKH under OKW, giving OKW command of forces on the Eastern Front.[5]

Setting different parts of the Nazi bureaucracy to compete for his favor in areas where their administration overlapped was a standard tactic employed by Hitler to reinforce his authority; and just as in other areas of government, there was a rivalry between the OKW and the OKH. Since most German operations during World War II were Army controlled (with Luftwaffe support), the OKH demanded control over German military forces. Nevertheless, Hitler decided against the OKH and in favor of the OKW overseeing operations in many land theaters. As the war progressed more and more influence moved from the OKH to the OKW, with Norway being the first "OKW war theater". More and more areas came under complete control of the OKW. Finally only the Eastern Front remained the domain of the OKH. However, as the Eastern Front was by far the primary battlefield of the German military, the OKH was still influential, particularly when on 19 December 1941 Hitler himself succeeded Walther von Brauchitsch as commander-in-chief of the OKH (Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres) during the Battle of Moscow.

The OKW ran military operations on the Western front, in North Africa, and in Italy. In the west, operations were further split between the OKW and Oberbefehlshaber West (OBW, Commander in Chief West), who was Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt (succeeded by Field Marshal Günther von Kluge).

There was even more fragmentation since the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe operations had their own commands (Oberkommando der Marine (OKM) and Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (OKL)) which, while theoretically subordinate, were largely independent from the OKW or the OBW.

During the entire period of the war, the OKW was led by Keitel, who reported directly to Hitler, from whom most operational orders actually originated as Oberster Befehlshaber der Wehrmacht (Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces). Albrecht von Hagen, a member of the failed assassination attempt on Hitler on 20 July 1944, was stationed here to be responsible for the courier service between military posts in Berlin and Hitler's secret military headquarters known as the Wolf's Lair.

International Military Tribunal

During the Nuremberg Trials, the OKW was indicted but acquitted of being a criminal organization like the Waffen-SS. Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl were convicted and sentenced to death by hanging. Jodl was posthumously acquitted of the main charges against him in 1952, six years after the sentence was carried out.

During the subsequent High Command Trial in 1947/48, several OKW members were charged with war crimes, especially for the Commissar Order to shoot Red Army political commissars in German-occupied countries, the killing of POWs and participation in the Holocaust. Eleven defendants received prison sentences ranging from three years including time served to lifetime imprisonment, two were acquitted on all counts, and one committed suicide during the trial.

Notes and references

- ↑ G.P. Megargee, "Triumph of the Null: Structure and Conflict in the Command of German Land Forces, 1939-1945," War in History (1997) 4#1 pp 60-80, online.

- ↑ Also known by title Amtsgruppe Auslandsnachrichten und Abwehr

- ↑ Also known by title Wehrwirtschaftsstab.

- ↑ Warlimont being replaced in September 1944 due to ill health by General August Winter.

- ↑ Howard D. Grier. Hitler, Dönitz, and the Baltic Sea, Naval Institute Press, 2007, ISBN 1-59114-345-4. p. 121

Further reading

- Megargee, G.P. "Triumph of the Null: Structure and Conflict in the Command of German Land Forces, 1939-1945," War in History (1997) 4#1 pp 60–80, online in EBSCO.

- Seaton, A. The German Army, 1939–1945 (St. Martin’s Press, 1982)

- Stone, David. Twilight of the Gods: The Decline and Fall of the German General Staff in World War II (2011).

- Wilt, A. War from the Top: German and British Decision Making During World War II (Indiana U. Press, 1990)

External links

- "Not the Stuff of Legend: The German High Command in World War II" – lecture by Dr. Geoffrey Megargee, author of Inside Hitler's High Command, available at the official YouTube channel U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center