Oliver Baldwin, 2nd Earl Baldwin of Bewdley

| The Right Honourable The Earl Baldwin of Bewdley | |

|---|---|

Baldwin as an officer of the Armenian army, 1920 | |

| Member of Parliament for Dudley | |

|

In office 1929–1931 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Maclay |

| Succeeded by | Dudley Jack Barnato Joel |

| Member of Parliament for Paisley | |

|

In office 1945–1947 | |

| Preceded by | Cyril Edward Lloyd |

| Succeeded by | Douglas Johnston |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

1 March 1899 Astley Hall, Worcestershire, United Kingdom |

| Died |

10 August 1958 (aged 59) London, United Kingdom |

| Political party | Labour |

Oliver Ridsdale Baldwin, 2nd Earl Baldwin of Bewdley (1 March 1899 – 10 August 1958), known as Viscount Corvedale from 1937 to 1947, was a British socialist politician who had a career at political odds with his father, the Conservative prime minister Stanley Baldwin.

Educated at Eton, which he hated, Baldwin left as soon as he could. After serving in the army during the First World War he undertook various jobs, including a brief appointment as an officer in the Armenian army, and wrote journalism and books on a range of topics. He served two terms as a Labour Member of Parliament between 1929 and 1947.

Baldwin never achieved ministerial office in Britain. His last post was as Governor of the Leeward Islands, from 1948 to 1950.

Life and career

Early years

Baldwin was born at Astley Hall, Worcestershire, the elder son of the businessman Stanley Baldwin and his wife Lucy, née Ridsdale.[1] Baldwin senior was elected a Conservative MP in 1908, and rose within fifteen years to become prime minister. He sent his son to Eton College, where the boy failed to fit in. He hated what he saw as the school's snobbery and cruelty,[2] and to his teachers he appeared to be "full of silliness, egotism, un-divine discontent, contempt for others (and of course for authority, discipline, tradition etc)".[3] He was keen to leave school and join the army to fight in the First World War,[4] and was commissioned in the Irish Guards in June 1917.[5] He did not join the fighting in France until June 1918,[6] but then distinguished himself by his bravery.[5] His war service strengthened his idealism and increasingly socialist views.[2]

Post-war and 1920s

After the war Baldwin served briefly as British Vice-Consul in Boulogne, and then travelled in north Africa. He refused to be supported by his father, and earned a living as a journalist and travel writer. A chance meeting in Alexandria led to an appointment as an infantry instructor in the newly-independent Armenia, but soon after he took up the post in 1920 the democratic government collapsed and Baldwin was imprisoned by Bolshevik-backed revolutionaries. He was freed two months later when democracy was restored, but en route back to Britain he was arrested by the Turkish authorities, accused of spying for Soviet Russia.[7] He was held for five months, in grim conditions, with execution a constant threat.[8] He later wrote a book about his experiences, called Six Prisons and Two Revolutions.[5]

After his release Baldwin returned to Britain, and in 1922 was briefly engaged to Dorothea ("Doreen") Arbuthnot, the daughter of a political ally of his father.[9] Coming to terms with the fact that he was homosexual, Baldwin broke off the engagement, and settled with John ("Johnnie") Boyle.[10] Described in The New Statesman as "a charming ne'er-do-well",[2] Boyle, who was six years older than Baldwin, became his lifelong partner.[11] Boyle's family came from Oxfordshire, where he and Baldwin set up home together, living in what the biographer Christopher J Walker describes as "gentle, amicable, animal-loving, primitive, homosexual socialism".[12]

At the 1924 general election Baldwin unsuccessfully contested the seat of Dudley for the Labour Party. By this time his father was leader of the Conservative Party and prime minister, and his son's candidacy attracted press comment.[5] At the 1929 election he won Dudley, and served as a backbench supporter of Ramsay MacDonald's Labour government, facing his defeated father across the House of Commons. Father and son remained on the warmest personal terms. Oliver's homosexuality was quietly accepted within the family, and in politics he refrained from personally attacking his father.[2]

Like other young left-wing Labour MPs, Baldwin was critical of MacDonald's insistence on strict financial management and refusal to launch large Keynesian public works programmes.[13] Early in 1931 Baldwin resigned from the Labour Party and was briefly associated with Oswald Mosley's New Party, but soon repudiated Mosley and rejoined Labour.[13] When MacDonald formed the National Government Stanley Baldwin and the Conservatives joined it; most Labour members, including Oliver Baldwin, did not. The 1931 general election resulted in a landslide win for the National Government and a disaster for Labour. Baldwin was among the casualties, defeated by a Conservative candidate, Sir Park Goff, who won by 19,991 votes to Baldwin's 10,837 at Chatham.[14] Baldwin returned to journalism. In Walker's view he was better known as a journalist than as a politician, writing anti-fascist articles in the usually pro-appeasement Rothermere press during the 1930s.[2] He also wrote what the reviewer Andrew Lycett calls "a curious novel called The Coming of Aissa, which emphasised the socialistic leanings of Jesus within an agnostic, Asian, neoplatonic context."[2]

Later years

Baldwin fought Paisley at the 1935 election, failing to be elected by 389 votes behind the Liberal candidate.[15] In 1937 Stanley Baldwin retired from politics and was created Earl Baldwin of Bewdley. As a result, Oliver Baldwin acquired the courtesy title Viscount Corvedale, which did not entail membership of the House of Lords. In 1939 he rejoined the army, becoming a major in the Intelligence Corps and serving in the Near East and north Africa.[5]

At the 1945 general election, when Labour returned to power under Clement Attlee, Corvedale was elected for Paisley with a majority of 10,330.[16] The Attlee government lacked representation in the House of Lords, which was dominated by Conservative peers. In 1947 Corvedale accepted the prime minister's offer of a peerage, but before he could take his seat his father died and Corvedale was automatically elevated as the second Earl Baldwin. Lycett comments that had it not been for the first earl's death Baldwin father and son would, uniquely, have sat opposite each other in both houses of parliament.[2]

In February 1948 Baldwin was appointed Governor and Commander in Chief of the Leeward Islands, a British colonial territory in the Caribbean.[17] Boyle accompanied him, to the disapproval of some of the British establishment in Antigua. Partly for this reason, and partly because Baldwin made no secret of his continuing socialist views or his desire for multiracial inclusiveness, he was recalled in 1950.[2]

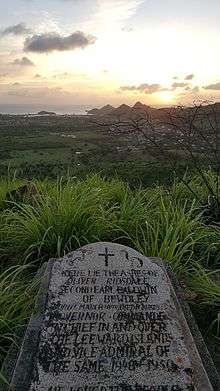

Baldwin died in Mile End Hospital, London, in 1958. He was succeeded in the earldom by his younger brother.[5] His ashes are interred on a hilltop on the island of Antigua. The stone inscription reads, Here lie the ashes of Oliver Ridsdale Second Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, Born March 1899 Died August 1958. Governor, Commander in Chief in and over the Leeward Islands and Vice Admiral of the same 1948 - 1950. He loved the people of these islands. RIP.

Books

- Konyetz: novel published under the pen name Martin Hussingtree, 1924

- Six Prisons and Two Revolutions: memoirs, 1924

- Socialism and the Bible (English translation of Les Principes du catholicisme social en face de l'Ecriture sainte by Jean-Samuel Ouvret), 1928

- Conservatism and Wealth: A Radical Indictment (with Roger Chance), 1929

- The Questing Beast: An Autobiography, 1932

- Unborn Son: political commentary, 1933

- The Coming of Aïssa: being the life of Aïssa ben Yusuf of El Naseerta, otherwise known as Jesus of Nazareth, 1935

- Oasis: political and social comment, 1936

- Source: Who Was Who.[1]

Notes

- 1 2 "Baldwin of Bewdley", Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2014, retrieved 4 August 2015 (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lycett, Andrew, ""An average MP; Oliver Baldwin: a life of dissent, by Christopher J Walker", New Statesman, London. 29 March 2004.

- ↑ Lyttelton and Hart-Davis, letter of 13 August 1958, pp. 115–116

- ↑ Walker, p. 22

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Obituary – Earl Baldwin of Bewdley", The Times, London. 12 August 1958. p. 8

- ↑ Walker, p. 31

- ↑ Walker, p. 69

- ↑ Walker, p. 75

- ↑ Walker, p. 88

- ↑ Walker, p. 99

- ↑ Walker, pp. 99–103

- ↑ Walker, p. 108

- 1 2 Walker, pp. 150–151

- ↑ "The General Election", The Times, 28 October 1931, p. 6

- ↑ "The General Election", The Times, 15 November 1935, p. 8

- ↑ "News in Brief", The Times, 13 September 1945, p. 2

- ↑ "Governor of Leeward Islands", The Times, 9 February 1948, p. 3

Sources

- Lyttleton, George; Rupert Hart-Davis (1981). Lyttelton/Hart-Davis Letters, Volume 3. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-3770-7.

- Walker, Christopher J (2003). Oliver Baldwin: A Life of Dissent. London: Arcadia. ISBN 978-1-900850-86-5.

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Earl Baldwin of Bewdley

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by W. R. Macnie (acting) |

Governor of the Leeward Islands 1948 – 1950 |

Succeeded by Sir Kenneth Blackburne |

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

| Preceded by Cyril Edward Lloyd |

Member of Parliament for Dudley 1929 – 1931 |

Succeeded by Dudley Jack Barnato Joel |

| Preceded by Joseph Maclay |

Member of Parliament for Paisley 1945 – 1947 |

Succeeded by Douglas Johnston |

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

| Preceded by Stanley Baldwin |

Earl Baldwin of Bewdley 1947 – 1958 Member of the House of Lords (1947) |

Succeeded by Arthur Windham Baldwin |