Paamese language

| Paamese | |

|---|---|

| Paama | |

| Native to | Vanuatu |

Native speakers | 6,000 (1996)[1] |

|

Austronesian

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

pma |

| Glottolog |

paam1238[2] |

Paamese, or Paama, is the language of the island of Paama in Northern Vanuatu. There is no indigenous term for the language; however linguists have adopted the term Paamese to refer to it. Both a grammar and a dictionary of Paamese have been produced by Terry Crowley.

Classification

Paamese is an Austronesian language of Vanuatu. It is most closely related to the language of Southeastern Ambrym. The two languages, while sharing 60-70% of the lexical cognate, are not mutually intelligible.

Geographic distribution

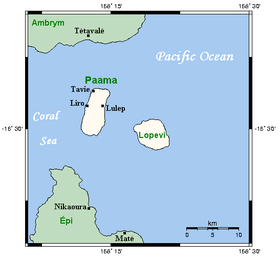

Paama itself is a small island in the Malampa Province. The island is no more than 5 km wide and 8 km long. There is no running water on the island except after heavy storms.

In the 1999 census in Vanuatu, 7000 people identified as Paamese. 2000 on the island itself and others through the urban hubs of Vanuatu, particularly Port Vila.

Dialects/Varieties

Paamese spoken in different parts of the island (and then those on other islands) does differ slightly phonologically and morphologically but not enough to determine definite ‘dialects splits’. Even in the extreme north and extreme south, places with the biggest difference, both groups can still communicate fully. There is no question of mutual intelligibility being impaired.

Phonology

Consonants

| labial | alveolar | velar/glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| prenasalised stop | b | d | g |

| oral stop | p | t | k |

| nasal | m | n | ŋ |

| fricative | f | s | h |

| lateral | l | ||

| trill | r | ||

| glide | y | w |

Vowels

| front | central | back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| high | i i: | u u: | |

| mid | e e: | o o: | |

| low | a a: |

Stress is phonologically distinctive in Paamese.

Writing system

There is a Paamese orthography which has been in use for over 75 years which accurately represents almost all of the consonant phonemes. The only point of difference is the labial fricative, which, although voiceless in most environments, is written ⟨v⟩. The velar nasal is written with the diagraph ⟨ng⟩. A long vowel is written with a macron over the vowel: ⟨ā, ē, ī, ō, ū⟩.

Grammar

Nominal phrases

In Paamese nominals can occur in four environments:

- as verbal subjects with cross-reference on the verb for person and number

- as verbal objects with cross-reference on the verb for properness.

- as prepositional objects

- as heads of nominal phrases with associated adjuncts

There are four major classes of nominals:

- Pronouns

- Indefinites

- Possessives

- Nouns

Pronouns

Free pronouns in paamese:

| person | SG | DL | PCL | PL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | inau | incl. | ialue | iatelu | iire |

| excl. | komalu | komaitelu | komai | ||

| 2 | kaiko | kamilu | kamiitelu | kamii | |

| 3 | kaie | kailue | kaitelu | kaile |

The paucal is generally used for numbers in the range of about 3 to 6, and the plural is generally used for numbers greater than 12. In the range 6 to 12, whether a speaker of Paamese uses paucal or plural is dependent on what the thing being spoken about is contrasted with. For example one’s patrilineage will be referred to paucally when it is contrasted with that of the whole village but plurally when it is contrasted with just the nuclear family. The paucal is also sometimes used even when it is referring to a really big number if it is contrasted with an even bigger number. For example comparing the population of Paama with that of Vanuatu as a whole. However using the paucal with numbers above a dozen is rare.

Indefinites

Unlike other nominals, indefinites can occur not only as nominal phrase heads, but also as adjuncts to other heads. There are two types of indefinites. The first are numerals. When Crowley was writing in 1982 he said that the numeral system of Paamese was not used by anyone under the age of 30 and only rarely by those older than 30. It is unlikely, therefore, that many people use it today.

The following is a list of the seven non-numeral indefinites in Paamese:

- sav - another (sg)

- savosav - other (non-sg)

- tetāi - any; koa(n), some

- tei - some of it/them

- haulu - many/much

- musav - many/much (archaic)

Possessives

All nouns fall into one of two subclasses using different constructions for possession. Categories can roughly be defined semantically into alienable and inalienable possession. Inalienability, semantically can be described as the relationship held between an animate possessor and an aspect of this possessor which can’t exist independently of that being.

Body parts are the most common inalienable possession but not all body parts are treated as inalienable; internal body parts are largely seen as alienable unless they are perceived to be central to emotions, individuality or maintenance of life itself. This can be explained through the experience of butchering or cooking of animals in which the internal organs are removed and thus alienated from the body. Exusions that are expelled in normal bodily functions are regarded as inalienable while those that are periodically expelled or as a result of sickness are regarded as alienable so bodily exusions such as urine, saliva, blood and excrement are treated as inalienable while sweat, blood clots and ear wax are alienable. An exception to this rule is vomit, however, which is treated as inalienable. Inalienability also extends to relations between people with blood relations being expressed in the alienable possessive construction

Inalienable and alienable possessions are marked using different possessive constructions. Inalienable possessions are marked with a possessive suffix attaching directly onto the noun

NOUN-SUFFIX vatu-k head-1SG ‘my head’

While alienable possessions are marked with a possessive constituent to which the possessive suffix attaches

NOUN POSS-SUFFIX vakili ona-k canoe POSS-1SG ‘my canoe’

The possessive suffix in both subclasses, however, is the same.

| person | SG | DL | PCL | PL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -k | INCL | -ralu | -ratel | -r |

| EXCL | -mal | -maitel | -mai | ||

| 2 | -m | -mil | -mitel | -mi | |

| 3 | -n | After -e | -alu | -atel | -ø |

| After -a/-o | -ialu | -iatel | -i | ||

| After -i/-u | -ialu | -latel | -l |

These classes are quite rigid and if an inalienable noun, semantically, can be alienated it would still have to be expressed using the inalienable construction.

Alienable possessions can be split into further subclasses represented by the different possessive constituent that the noun takes, again these have a semantic correspondence indicating the relationship between the possessed noun and the possessor

- A-n ‘his/her/its (to eat); ‘intended specially for him/her/it’; ‘specially characteristic of him/her/it’

- Emo-n ‘his/her/its (to drink, to wear, to use domestically) ’

- Ese-n ‘his/her (owned as something that one has planted, as an animal one has reared, or as something kept on one’s own land) ’

- One-n ‘his/her/its (in all other kinds of possession) ’

These subclasses are not so rigid and a noun can be used with different possessive constituent according to its use.

When the possessed noun isn’t a pronoun, the third person singular possessive suffix is attached to the possessed noun, which is then followed by the possessor noun

Ani emo-n ehon

coconut POSS:POT-3SG child

‘child’s drinking coconut’

If the possessed noun is inalienable, the third person singular suffix attaches directly to the noun with the possessor noun following

Vati-n ehon head-3SG child ‘child’s head’

No morpheme of any kind can intervene between a possessive suffix and the possessed noun in this construction.

Nouns

There are five subtypes of nouns in Paamese. The first are individual names of people or animals, that is of some particular person or animal. So Schnookims or Fido rather than cat or dog. Individual names are cross-referenced on the verb in object position with the same suffix used for pronouns (-e/-ie), rather than the suffix used for non-proper objects (-nV).

Location nouns

There are two kinds of location nouns, relative and absolute. The relative nouns are a closed class of 10 words with meanings like above or nearby. The absolute nouns are an open class and refer to some specific location. Location nouns generally occur in the spatial case. Unlike all other nouns, in this case they take a zero marking rather than the preposition ‘eni’. Relative location nouns are distinguished grammatically from the absolute location nouns on the basis that they can freely enter into prepositionally linked complex nominal phrases while the absolute nouns cannot.

Time nouns

Time nouns are distinguished from other nouns grammatically on the basis that they can only be in the oblique or relative case. Like location nouns they come in two delicious flavours. The first can only receive a zero marking in the oblique case while the second can marked with either a zero marking or with the prepositions eni or teni.

Descriptive nouns

Are marginal members of the noun category. Semantically the describe some property or quality attributed to something and grammatically they usually behave like adjectives, that is they occur as adjuncts in a copular verb phrase. However unlike adjectives they do occasionally appear in distinctly nominal slots such as in the subject or object position to a verb. Further, unlike an adjective, they cannot simply follow a head noun as an adjunct.

Common nouns

Common nouns are essentially the dumping ground for everything that I haven’t mentioned yet. They are characterised grammatically as not having any of the special grammatical restrictions that apply to the other nouns and also by the verb taking the non-proper suffix (-nV) when a common noun is in the object position. Semantically they include anything that can be considered alienable or inalienable.

Verb phrases

Paamese demonstrates extensive inflectional morphology on verbs, distinguishing between a number of different modal categories that are expressed as prefixes. Verb phrases in Paamese are distinguishable as they have as their head a member of the class of verbs followed by its associated verbal adjuncts and modifiers.

Verb roots

The verb root form is bounded on the left by subject-mood prefixes and on the right by inflectional suffixes and the root itself differs in form according to the nature of the environment it occurs in. Verb roots fall into one of six different classes according to the ways that the initial segment inflects. This inflection is demonstrated in the following table.

| Class | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | t- | t- | r- | d- |

| II | k- | k- | k- | g- |

| III | k- | Ø- | k- | g- |

| IV | h- | h- | v- | v- |

| V | Ø- | Ø- | Ø- | mu- |

| VI | Ø- | Ø- | Ø- | Ø- |

Each of the four root forms denotes a specific set of morpho-syntactic environments;

- A

- as the second part of a compound noun

- B

- in all affirmative irrealis moods of the verb

- when there is some preceding derivational morpheme

- when there is no preceding morpheme and the verb carries the nominaliser –ene

- C

- as an adjunct to a verb phrase head

- D

- in the realis mood of the verb

- in the negative form of the verb

A verb is entered into the lexicon in its A-form.

Transitive verbs can be further subdivided into classes according to the variation of the final segment of the root

| Class | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -e | -a | -aa |

| 2 | -o | -a | -aa |

| 3 | -a | -a | -aa |

| 4 | -V | -V | -V |

- X

- word finally

- before the common object cross reference suffix –nV

- before a reduplicated part of a word

- Y

- before bound object pronouns

- before the common object cross-reference suffix –e/-ie

- Z

- before the partitive suffix –tei

- before the nominalising suffix –ene

Inflectional Prefixes

Inflectional prefixes attach onto the verb phrase head in the following order

- Subject marker + mood marker + negative marker + stem

The syntactic position of the verb phrase head can be defined by the fact that is the only obligatorily filled slot in the phrase.

The subject and mood prefixes are normally clearly distinguishable morphologically, however there is morphological fusion in some conjunctions of categories producing portmanteau morphemes that mark both subject and mood.

Subject Prefixes

The subject constituent cross-references for the person and number of the subject and also expresses the mood

| Person | sg. | dl. | pcl. | pl. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | na- | incl. | lo- | to- | ro- |

| excl. | malu- | matu- | ma- | ||

| 2 | ko- | mulu- | mutu- | mu- | |

| 3 | ø | lu- | telu- | a- |

Mood Prefixes

- Realis: ø

- Immediate: va-

- Distant: portmanteau

- Potential: na-

- Prohibitive: potential +partitive suffix -tei

- Imperative: portmanteau

Distant portmanteau subject-mood prefixes are as follows

| Person | sg. | dl. | pcl. | pl. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ni- | incl. | lehe- | tehe- | rehe- |

| excl. | male- | mate- | mahe- | ||

| 2 | ki- | mele- | mete- | mehe- | |

| 3 | he- | lehe- | tele- | i- |

Imperative portmanteau subject-mood prefixes are as follows

- Sg: ø-

- Dl: lu-

- Pcl: telu-

- Pl: alu-

Negation

The negative marker is always morphologically distinct from the other orders of prefixes. Negation is marked by means of the prefix ro- added between the subject/mood markers and the root. The affirmative is marked by absence of this morpheme.

There are two types of negation when a sentence is in partitive case. In the first type, the verb must take the partitive suffix –tei and in the second, this suffix is optional.

Inflectional Suffixes

There are three sets of inflectional suffixes; those expressing bound pronominal objects, those expressing the common-proper marking of a free form object, and that which marks the verb as being partitive.

Bound Pronominal Objects

A singular pronominal object can be expressed as a suffix. There are two sets of bound object markers.

| Person | I | II |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | -nau | -inau |

| 2 | -ko | -iko |

| 3 | -e | -ie |

The first set is used with the greatest number of verbs, the second set is used only with roots ending in –e and those belonging to Class IV (see above). Class I verbs cannot take the first person singular bound object, although they can take the second and third person objects.

Common-proper Objects

When a transitive verb is followed by a free form object, this is cross-referenced on the verb according to whether it is common or proper with certain phonological categories of verb stems. When the object is a name or a pronoun this is marked on certain verbs by the suffix –i/-ie. When the verb has a common object, this is cross-referenced with the suffix –nV

Reduplication

Reduplication has a fairly wide range of semantic functions in Paamese and can in some cases even change the class which a form belongs. When a verb is reduplicated, the new verb can differ semantically from its corresponding unreduplicated form in that it describes an event that is not seen has having a spatial or temporal setting or a single specific patient. When a numeral verb is reduplicated, the meaning is that of distribution. Reduplication can occur in a number of ways, it can reduplicate just the initial syllable, the initial two syllables or the final two syllables with no consistent semantic difference between these three types.

Adjuncts

A verb phrase can contain one or more adjuncts always following the head of the verb phrase. All of the inflectional suffixes above attach onto the last filler of the adjunct slot and if there is no adjunct, onto the verb phrase head. There are two different types of adjuncts, tightly bound and loosely bound. A tightly bound adjunct must always be followed by the inflectional suffixes as no constituent can intervene between it and the verb phrase head. Tightly bound adjuncts include prepositional and verbal adjuncts and adjectival adjuncts to a non-copula verb phrase head. A loosely bound adjunct can have inflectional suffixes attached to either the final adjunct or the verb phrase head. All adjuncts to the copula verb, nominal adjuncts in the ‘cognate object’ construction and modifiers are loosely bound. The ‘cognate object’ construction is one in which there is an intransitive verb in the position of the head and a loosely bound nominal phrase adjunct following the head. The transitivity of the final adjunct determines the transitivity of the entire verb phrase.

The Serial Verb Construction

By far the most common adjunct is a verb stem itself; this construction is called a serial verb construction. In this construction, prefixes attach to the head and suffixes to the final constituent of the adjunct slot, thus marking this a tightly bound adjunct. It is not often possible to predict the meanings of serial verbs in Paamese and there are a large number of verbal adjuncts which do not occur as heads themselves.

Clauses

Declarative clauses

There are three types of morphosyntactic relationship between phrase-level constituents:

- (NP)(VP) A clause may contain one or more NP. The NPs may be subjects, objects, prepositional objects, or a bound complement.

- (NP)(NP) NPs may relate to each other as part of a prepositional construction or the bond complement construction.

- There is also a third type that holds between modifiers and other constituents.

Yes/no Questions

There are four types of yes/no questions.

Intonation Questions

This takes the syntactic form of a declaritive however while a declaritive typically ends in falling intonation whereas a rise-fall turns the clause into a question.

Opposite Polarity Questions

This takes the form of a semantically negative declaritive clause. This is used as a polite way of asking permission for something.

Tag Questions

This takes the form of a declaritive clause with the tag "aa" placed at the end. This takes a sharply rising intonation.

Opposite Polarity Tag Questions

There are two different types of opposite polarity tag, "vuoli" and "mukavee". There is no appreciable difference in meaning between these two forms.

content questions

These take the form of a declaritive clause but insert one of the following words into the syntactic slot that information is being requested about:

- asaa asking about nouns with non-human reference

- isei asking about nouns with human reference

- kavee asking about location nouns, or which of a number on non-human nouns

- nengaise asking about time nouns

Vocabulary/Lexis

Kinship Terms:

- Tamen- father

- Latin- mother

- Auve- grandparent

- Natin- son/daughter

- Tuak- brother of a man, sister of a woman

- Monali- brother of a woman

- Ahinali- sister of a man

- Uan- brother/sister in law

Bislama is contributing to the vocabulary of Paamese especially for new kinds of technology, items foreign to local paamese and for the slang of the younger generation. Some examples of these follow.

| Bislama | Paamese | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| Busi (Fr. Bougie) | Busi | Spark plug |

| Botel (E. Bottle) | Votel | Bottle |

| Kalsong (Fr. Caleçon) | Kalsong | Men's underpants |

Examples

- More tuo! Kovahāve?- Hello friend! Where are you going?

- Keik komuni nanganeh kovī aek vasī vāsi vārei. - You were drunk out of your mind when you were drinking yesterday.

References

- ↑ Paamese at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Paama". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Crowley, Terry (1982). The Paamese language of Vanuatu. Canberra, Australia: Pacific linguistics. ISBN 0-85883-279-8.

- Crowley, Terry (1996). "Inalienable possession in Paamese grammar". In Chappell, Hilary; McGregor, William. The Grammar of Inalienability - A Typological Perspective on Body Part Terms and the Part-Whole Relation. Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 383–432. ISBN 3-11-012804-7.

- Crowley, Terry (1992). A dictionary of Paamese. Canberra, Australia: Pacific Linguistics. ISBN 0-85883-412-X.