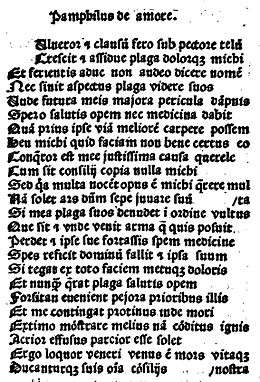

Pamphilus de amore

Pamphilus de amore (or, simply, Pamphilus) is a 780-line, twelfth-century Latin comedic play, probably composed in France but possibly Spain.[1] It was 'one of the most influential and important of all the many pseudo-Ovidian productions concerning the "arts of Love" ' in medieval Europe,[2] and 'the most famous and influential of the medieval elegiac comedies, especially in Spain'.[3] The main protagonists are Pamphilus and Galatea. Pamphilus seeks to woo Galatea through the mediation of a procuress (inspired by the procuress in Book 1.8 of Ovid's Amores).[4]

Style

According to Thomas Jay Garbaty, 'The Latin original abounds in all aspects of medieval rhetoric as outlined by Geoffrey de Vinsauf, in his Poetria Nova, specifically repetitio, paradox, oxymoron, alliteration. It is obvious that the author sacrificed much dramatic tension and liveliness for elegance of style'.[5]

Influence

Pamphilus de amore gave rise to the word pamphlet, in the sense of a small work issued by itself without covers because the poem was popular and widely copied and circulated on its own, forming a slim codex. The word came into Middle English ca 1387 as pamphilet or panflet.[6][7]

Pamphilus swiftly became widely read: it was quoted and anthologised already in England, France, Provence, and Italy in the early thirteenth century. It is first attested in the Netherlands c. 1250, in Germany c. 1280. It is attested in Castile by c. 1330. It remained popular in England into the late fifteenth century.[8] It was translated into Old Norse in the thirteenth century, as Pamphilus ok Galathea,[9] and into French by Jean Brasdefer as Pamphile et Galatée (c. 1300×1315).[10]

John Gower and Geoffrey Chaucer knew the poem, Chaucer drawing on it particularly in The Franklin's Tale and Troilus and Criseyde; it also influenced the Roman de la Rose; Boccaccio's Fiammetta drew inspiration from it; and it was adapted in Juan Ruiz's Don Melon/Dona Endrina episode in the Libro de Buen Amor (from the earlier fourteenth century.[11]

Editions and translations

- Alphonse Baudouin (ed.), Pamphile, ou l'Art d'étre aimé, comédie latine du Xe siècle (Paris, 1874)

- Jacobus Ulrich (ed.), Pamphilus, Codici Turicensi (Zurich, 1983)

- Gustave Cohen, La "Comédie" latine en France au 12e siècle, 2 vols (Paris, 1931)

- Adolfo Bonilla and San Martín, Una comedia latina del siglo XII: (el "Liber Panphili"); reproducción de un manuscrito inédito y versión castellana, Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia, 70: Cuaderno, V (Madrid: Imp. de Fortanet, 1917)

- Thomas Jay Garbáty, 'Pamphilus, de Amore: An Introduction and Translation', The Chaucer Review, 2 (1967), 108-34, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25093043 [English translation]

References

- ↑ Vincente Cristóbal, 'Ovid in Medieval Spain', in Ovid in the Middle Ages, ed. by James G. Clark, Frank T. Coulson and Kathryn L. McKinley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 231-56 (p. 241).

- ↑ Thomas Jay Garbaty, 'Pamphilus, de Amore: An Introduction and Translation', The Chaucer Review, 2 (1967), 108-34 (p. 108), http://www.jstor.org/stable/25093043.

- ↑ Vincente Cristóbal, 'Ovid in Medieval Spain', in Ovid in the Middle Ages, ed. by James G. Clark, Frank T. Coulson and Kathryn L. McKinley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 231-56 (p. 241).

- ↑ Vincente Cristóbal, 'Ovid in Medieval Spain', in Ovid in the Middle Ages, ed. by James G. Clark, Frank T. Coulson and Kathryn L. McKinley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 231-56 (p. 241).

- ↑ Thomas Jay Garbaty, 'Pamphilus, de Amore: An Introduction and Translation', The Chaucer Review, 2 (1967), 108-34 (p. 110), http://www.jstor.org/stable/25093043.

- ↑ OED s.v. "pamphlet".

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "pamphlet". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Thomas Jay Garbaty, 'Pamphilus, de Amore: An Introduction and Translation', The Chaucer Review, 2 (1967), 108-34 (p. 108), http://www.jstor.org/stable/25093043.

- ↑ Marianne E. Kalinke and P. M. Mitchell, Bibliography of Old Norse–Icelandic Romances, Islandica, 44 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985), p. 86.

- ↑ Thomas Jay Garbaty, 'Pamphilus, de Amore: An Introduction and Translation', The Chaucer Review, 2 (1967), 108-34 (p. 108), http://www.jstor.org/stable/25093043.

- ↑ Thomas Jay Garbaty, 'Pamphilus, de Amore: An Introduction and Translation', The Chaucer Review, 2 (1967), 108-34 (pp. 108-9), http://www.jstor.org/stable/25093043.