Parasitic nutrition

Parasitic nutrition is a mode of heterotrophic nutrition where an organism (known as a parasite) lives on the body surface or inside the body of another type of organism (known as a host). The parasite obtains nutrition directly from the body of the host. Since these parasites derive their nourishment from their host, this symbiotic interaction is often described as harmful to the host. Parasites are dependent on their host for survival, since the host provides nutrition and protection. As a result of this dependence, parasites have considerable modifications to optimise parasitic nutrition and therefore their survival.

Parasites are divided into two groups: endoparasites and ectoparasites. Endoparasites are parasites that live inside the body of the host, whereas ectoparasites are parasites that live on the outer surface of the host and generally attach themselves during feeding.[1] Due to the different strategies of endoparasites and ectoparasites they require different adaptations in order to acquire nutrients from their host.

Parasites require nutrients to carry out essential functions including reproduction and growth. Essentially, the nutrients required from the host are carbohydrates, amino acids and lipids. Carbohydrates are utilised to generate energy, whilst amino acids and fatty acids are involved in the synthesis of macromolecules and the production of eggs.[2] Most parasites are heterotrophs, so they therefore are unable to synthesise their own 'food' i.e. organic compounds and must acquire these from their host.

Endoparasitism

enderoparasite is parasites which live inside the body of the host. This group includes helminths, trematodes and cestodes. Endoparasites are two groups of parasites: intercellular and intracellular parasites. Intercellular parasites live in spaces within the host e.g. the alimentary canal, whereas intracellular parasites live in cells within the host e.g. erythrocytes. Intracellular parasites typically rely on a third organism, a vector, to transmit the parasite between hosts.[1][3] Rather than requiring adaptations to penetrate the host, as ectoparasites do, endoparasites are in a nutrient-rich location so they instead have adaptations to maximise nutrient absorption. Endoparasites have a readily available and renewable supply of nutrients inside the host, which in some cases is pre-digested by the host, so mechanisms of nutrient absorption across their body surface is a common feature.[1] As part of their life cycle strategy, endoparasites must also be able to transmit from within the host body and survive the hostile environment within the host. Only by achieving this can they benefit from acquiring nutrition in this way.

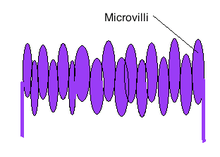

Endoparasites have various anatomical and biochemical adaptations, typically at the host-parasite interface, to maximise nutrient acquisition. One such adaptation is the tegument, a metabolically active external cover which plays an important role in the acquisition of nutrients from the host.[2] The parasite tegument is permeable to various organic solutes and has transporters for the facilitated or active uptake of nutrients. Various studies have attempted to characterise these transporters in a number of parasites e.g. the amino acid transporter molecules in protozoa.[2][4][5] Cestodes do not have a gut so the tegument is therefore critical for nutrient uptake. In cestodes the tegument is highly efficient with spine-like microtriches, similar to microvilli, to increase the surface area available for nutrient acquisition.[6] In many parasites the tegument structure has folds or microvilli to maximise the surface area available for diffusion and uptake of nutrients. The tegument also commonly has additional organelles and features with important functions in metabolism including the glycocalyx. The glycocalyx is a carbohydrate-rich layer which enhances nutrient absorption and secretes enzymes to aid primary digestion.[7]

Another important adaptation of endoparasites is the gut, which digests host macromolecules into soluble utilisable products.[2] This feature is particularly important in endoparasites which are not located in the alimentary canal and therefore the supply of nutrients is not pre-digested by the host. The gut lining typically has a layer of endodermal cells which secrete proteolytic enzymes to aid digestion. Some endoparasites have both a gut and anus, some lack an anus and some have neither i.e. those residing in the alimentary canal which instead diffuse pre-digested host nutrients across their body surface.[2]

The relative importance of the tegument, gut and other adaptations involved in nutrient acquisition varies between different endoparasitic species.

Tapeworms

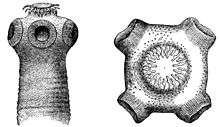

Tapeworms are endoparasites which have numerous adaptations to enhance parasitic nutrition. Tapeworms live in the small intestine of humans, providing an ideal location to access a readily available, rich source of pre-digested nutrients.[8] Since nutrients in the small intestine are plentiful and pre-digested by the host, tapeworms do not require a gut and instead have adaptations to maximise nutrient absorption. Tapeworms have a tegument which allows nutrients to be absorbed directly from the host small intestine by diffusion. They also have anatomical adaptations in the form of a scolex with hookers and suckers to allow the parasite to attach to the host small intestine wall, preventing the tapeworm from being egested following peristalsis.[2] Tapeworms have a flattened body with microtriches to maximise the surface area available for nutrient absorption and they additionally have various transporter molecules. Tapeworms have to compete with the host epithelium for nutrients, so it is essential that they compete more efficiently for nutrients. They also secrete enzymes to enhance host digestive enzymes e.g. pancreatic α-amylase.[2]

Schistosomes

Schistosomes, another type of endoparasite, also live inside the body of the host but instead these parasites acquire their nutrients from host blood. Schistosomes are in direct contact with host blood, a rich source of amino acids, and they therefore do not require penetrative structures to reach host nutrients. Schistosomes take blood up through the negative pressure created by muscle contractions of their sucker and oesophagus.[2] They obtain amino acids from host blood through a mechanism of haemoglobin degradation, which remains unresolved but is suggested to involve a series of proteases. Mechanisms to overcome blood clotting are also employed.[9][10] Various studies have attempted to characterise the components of the schistosome tegument, including transporter molecules suggested to be involved in nutrient uptake. Such transporter molecules include schistosome alkaline phosphatase (SmAP) and cathepsin B, which are suggested to be important in nutrient acquisition.[4][10][11]

Malaria

Malaria, caused by the apicomplexan parasite Plasmodium falciparum, is an intracellular endoparasite. This parasite relies on a third organism, in the form of an Anopheles mosquito vector. The host blood provides an ideal rich source of glucose and amino acids to the parasite, particularly during blood stage infection where Plasmodium infects erythrocytes.[12] In order to acquire essential nutrients Plasmodium has to compete with both the vertebrate and insect host and therefore must be highly efficient, regulating uptake according to nutrient availability.[12] Plasmodium, along with many other endoparasitic parasites, have numerous channels in their parasitophorous vacuole membrane rendering it permeable to organic solutes to allow the uptake of necessary nutrients. The Plasmodium falciparum hexose transporter (PfHT) is such a transporter, which is critical for the uptake of glucose and fructose and therefore survival of the parasite.[13] These organic molecules have to cross three membranes altogether; the plasma membrane of the erythrocyte, the parasitophorous vacuole membrane and the Plasmodium plasma membrane, facilitated by transporters such as PfHT.[14]

Ectoparasitism

Ectoparasites live on the outer surface of the host. This group includes ticks, leeches, mites and the tsetse fly. Ectoparasites do not have a readily available source of nutrients available on the outer surface of the host so they therefore require adaptations which enable them to gain access to host nutrients. This requires penetrative features which can insert into the host, as well as the ability to secrete digestive enzymes and the presence of a gut to digest host-derived nutrients.[1] Ectoparasites also have a variety of parasite transporters and permeases to enable them to acquire nutrition from their host, across numerous membranes. Many ectoparasites are known to be vectors of pathogens, so they therefore transmit these pathogens during nutrient acquisition.[15]

Tsetse flies, the insect vector of Trypanosoma brucei, the causative agent of African trypanosomiasis are an example of an ectoparasite. These insects have specialised structures, known as a proboscis to pierce and draw nutrients from their host. These then employ transport proteins to transport the essential nutrients across membranes, ultimately from the host to the tsetse fly gut for digestion. Various permeases have been characterised including those that import hexoses, carboxylates, and amino acids.[16][17]

Another ectoparasite is scabies, caused by Sarcoptes scabiei. Scabies, transmitted by female mites, depends on nutrition from its host for survival. This ectoparasite obtains nutrients by burrowing into the skin of the host. Studies have also identified the presence of scabies mite inactivated protease paralogues (SMIPPs), which are believed to compete with host proteases.[18]

Effects on the host

Parasitic nutrition is beneficial to the parasite but typically detrimental to the host since it deprives the host of nutrients. This mode of nutrition has numerous side effects on the host including weight loss, anaemia, obstruction of the intestine, damage to the host intestinal wall and in some cases transmission of serious pathogens e.g. the ectoparasitic tsetse fly which transmits African trypanosomiasis.[1][2][8][12]

Applications

Nutrient acquisition is an important component of parasite pathogenesis since it is critical to parasite survival.[12] Understanding the mechanisms of parasite nutrient acquisition therefore identifies novel targets which we can exploit as a form of parasite control e.g. through knock-out or inhibition of crucial transporters or destruction of penetrative anatomical features. Several studies have looked into nutrient acquisition as a method of parasite control, including the development of vaccines against helminth parasites by targeting digestive proteases.[19]

Parasitic nutrition in plants

Plants are typically autotrophic organisms meaning that they synthesise their own 'food' from inorganic compounds by photosynthesis. Some plants however are unable to synthesise their own 'food' by photosynthesis and therefore acquire nutrients by parasitic nutrition from other living plants. Plants which acquire their nutrients in this way are known as parasitic plants.[20] These plants have modified root structures known as haustorium, which the parasitic plants use to penetrate the vascular bundle of host plants and essentially 'steal' nutrients from host plants.[1][21]

Parasitic plants include Dodder, Rafflesia and Broomrape.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cain; et al. (2011). "13". Parasitism (Second ed.). Sinauer Associates.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Dalton; et al. (2004). "Role of the tegument and gut in nutrient uptake by parasitic platyhelminths". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 82: 211–232. doi:10.1139/Z03-213.

- ↑ Sibley LD (2004). "Intracellular Parasite Invasion Strategies". Science. 304: 248–253. doi:10.1126/science.1094717.

- 1 2 Bhardwaj and Skelly (2011). "Characterization of Schistosome Tegumental Alkaline Phosphatase (SmAP)". PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 5: 1–8. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001011.

- ↑ Jackson AP (2007). "Origins of amino acid transporter loci in trypanosomatid parasites". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 1–17. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-26.

- ↑ McManus DP (2009). "Reflections on the biochemistry of Echinococcus: past, present and future". Parasitology. 136: 1643–1652. doi:10.1017/S0031182009005666.

- ↑ Reitsma; et al. (2007). "The endothelial glycocalyx: composition, functions, and visualization". European Journal of Physiology. 454: 345–359. doi:10.1007/s00424-007-0212-8.

- 1 2 Shrihari; et al. (2011). "Intestinal Perforation due to Tapeworm: Taenia Solium". Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 5: 1101–1103.

- ↑ Hall; et al. (2011). "Insights into blood feeding by schistosomes from a proteomic analysis of worm vomitus". Molecular & Biochemical Parasitology. 179: 18–29. doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.05.00.

- 1 2 Bos; et al. (2009). "Analysis of regulatory protease sequences identified through bioinformatic data mining of the Schistosoma mansoni genome". BMC Genomics. 10: 1–14. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-488.

- ↑ Delcroix; et al. (2006). "A multienzyme network functions in intestinal protein digestion by a platyhelminth parasite". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 22: 39316–29.

- 1 2 3 4 Landfear SM (2011). "Nutrient Transport and Pathogenesis in Selected Parasitic Protozoa". Eukaryotic Cell. 10: 483–493. doi:10.1128/EC.00287-10.

- ↑ Slavic; et al. (2010). "Life cycle studies of the hexose transporter of Plasmodium species and genetic validation of their essentiality". Molecular Microbiology. 75: 1402–13. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07060.x.

- ↑ Leirião; et al. (2004). "Survival of protozoan intracellular parasites in host cells". European Molecular Biology Organisation Reports. 5: 1142–1147. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400299.

- ↑ Nieto; et al. (2007). "Ectoparasite diversity and exposure to vector-borne disease agents in wild rodents in central coastal California". Journal of Medical Entomology. 44: 328–335. doi:10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[328:edaetv]2.0.co;2.

- ↑ Geiser; et al. (2005). "Molecular Pharmacology of Adenosine Transport in Trypanosoma brucei: P1/P2 Revisited". Molecular Pharmacology. 68: 589–595. doi:10.1124/mol.104.010298.

- ↑ Igoillo-Esteve; et al. (2011). "Glycosomal ABC transporters of Trypanosoma brucei: Characterisation of their expression, topology and substrate specificity". International Journal of Parasitology. 41: 429–438. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.11.002.

- ↑ Henggae; et al. (2006). "Scabies: a ubiquitous neglected skin disease". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 6: 769–779. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(06)70654-5.

- ↑ Pearson; et al. (2010). "Blunting the knife: development of vaccines targeting digestive proteases of blood-feeding helminth parasites". Biological Chemistry. 391: 901–911. doi:10.1515/bc.2010.074.

- ↑ Plant Defense: Warding Off Attack by Pathogens, Herbivores and Parasitic Plants (First ed.). John Wiley and Son. 2010.

- ↑ Marquardt; et al. (2010). "Constraints on host use by a parasitic plant". Oecologia. 164: 177–184. doi:10.1007/s00442-010-1664-7.