Party line (telephony)

A party line (multiparty line, shared service line, party wire) is a local loop telephone circuit that is shared by multiple telephone service subscribers.[1][2][3]

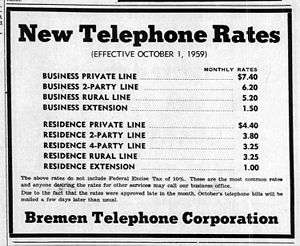

Party line systems were widely used to provide telephone service, starting with the first commercial switchboards in 1878.[4] A majority of Bell System subscribers in the mid-20th century in the United States and Canada were serviced by party lines, which carried a billing discount over individual service; during wartime shortages, these were often the only available lines. British users similarly benefited from the party line discount. Farmers in rural Australia used party lines, where a single line spanned miles from the nearest town to one property and on to the next.[5]

History

_(14569629440).jpg)

Telephone companies offered party lines since the late 1800s,[6] although subscribers in all but the most rural areas may have had the option to upgrade to private line service at an additional monthly charge. The service was common in sparsely-populated areas where remote properties are spread across large distances, such as Australia (where these were operated by the Government Post Master General department). In rural areas in the early 20th century, additional subscribers and telephones, often numbered in several dozen, were frequently connected to the single loop available.

Party lines provided no privacy in communication. They were frequently used as a source of entertainment and gossip, as well as a means of quickly alerting entire neighbourhoods of emergencies such as fires,[7] becoming a cultural fixture of rural areas for many decades.

The rapid growth of telephone service demand, especially after World War II, resulted in a large fraction of party line installations in the middle of the 20th century in the United States. This often led to traffic congestion in the telephone network, as the line to a destination telephone was often busy.[8] Nearly three-quarters of Pennsylvania residential service in 1943 was party line, with users encouraged to limit calls to five minutes.[9] Shortages persisted for years after each war; private lines in Montreal remained in short supply at the end of 1919[10] and similar shortages were reported by telephone companies in Florida as late as 1948,[11][12] Some rural users had to run their own wires to reach the utility's lines.[13]

Objections about one party monopolizing a multi-party line were a staple of complaints to telephone companies and letters to advice columnists for years[14] and eavesdropping on calls remained an ongoing concern.[15]

In December 1942, University of Tennessee's strategy in an American football game versus University of Mississippi was revealed to the opposing coach as a telephone on the Ole Miss team's bench had been inadvertently wired to the same party line.[16] In May 1952, an alleged bookmaking operation in St. Petersburg, Florida was shut down after one month of operation in a rented storefront using a party line telephone.[17] In June 1968, the conviction of three Winter Park, Florida men on bookmaking charges was overturned as police had used a party line telephone in a rented house on the same line as the suspects to unlawfully intercept their communications.[18]

In 1956, Southern Bell officials refused a request from a public utilities commissioner in Jackson, Mississippi to segregate party telephone lines on racial boundaries.[19]

While primitive lockout devices to prevent two subscribers from picking up the same line at the same time were proposed relatively early,[20] multiple simultaneous calls did not become viable until the initial tests of transistorised pair gain devices in 1955.[21][22] Any handset off-hook therefore tied up the line for everyone.

Many jurisdictions require a person engaged in a call on a party line to end the call immediately if another party needs the line for an emergency. Such laws also provide penalties for abuse by falsifying emergency situations. In May 1955, a Poughkeepsie, New York woman was indicted by a grand jury after her refusal to relinquish a party line delayed a volunteer firefighter's effort to report a grass fire; the fire destroyed a shed and a barn.[23][24] She was given a suspended sentence.[25] In June 1970, a sixteen-year-old girl and a woman were charged after refusing to relinquish a party line to allow a distress call as three boys drowned in a pond in Walsenburg, Colorado.[26][27][28][29][30]

By the 1980s, party lines were displaced in most localities as they could not support subscriber-owned equipment such as answering machines and computer modems. The electro-mechanical switching equipment required for their operation was rapidly becoming obsolete, supplanted by electronic and digital switching equipment. The new telephone exchange equipment offered vertical service code calling features such as call forwarding and call waiting, but often was incompatible with multi-party lines.

In 1971, Southern Bell had announced plans for phase-out of party lines in North Carolina.[31] In 1989, the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company replaced party lines with private lines in Talcott, West Virginia, a rural area which once had as many as sixteen subscribers on one line.[32] In 1991, Southwestern Bell set out to replace all of its party lines in Texas with private lines by 1995.[33] Woodbury, Connecticut's independent telephone company abandoned its last party lines in 1991, the last in that state to do so.[34]

Party lines in the United States were ineligible for Universal Service Fund subsidies and telephone companies converted them to private lines to benefit from the subsidies. Universities also phased out the systems, which were once common in student dormitories. Illinois State University terminated its last party line in 1990.[35]

One of the last manual telephone exchanges with party lines in Australia was closed down in 1986 in the township of Collarenebri, where most town residents had a telephone number of only three digits, and to make a call outside the exchange area it was necessary to call the exchange to place a call. For rural residents, many were on a single telephone line identified by a number and a property name, for example one party line was called Gundabluie 1 line. Each party on that single line was identified by a letter, and so to call that party, the exchange would be called and the number asked for would be Gundabluie 1 S for example. The exchange rang a distinct ring down the Gundabluie 1 line, signalling the party's corresponding letter in Morse code. This distinctive ring would alert all parties on the line who the call was for. Three short rings signified the call was for the party with the S letter and so on.

Selective ringing

To signal specific subscribers on party lines selectively, telephone operating companies implemented various signaling systems.

The earliest selective system was the code ringing system, in which each telephone subscriber was assigned a specific ringing cadence, (not to be confused with modern ring tones).

Although various systems were implemented, one that limited the number of coded rings but established a uniform and readily understood format, was to first give the subscriber number as individual digits, which could be from one to four digits long per exchange,[36] separated by the instructional word "ring" followed by the two digits of the ring code where the first digit indicated the number of long rings, followed by the second digit indicating the number of short rings. Thus spoken, for example, as "nine, three; ring two, two" to mean subscriber No. 93 with ringing code 2 long and 2 short, and written as "93R22", (and if outside the given exchange, then the exchange would be asked for by name before the requested number and ringing code, e.g. "Rockridge nine, three; ring one, two" i.e. "(On the) Rockridge (exchange), (subscriber No.) nine, three; ring one long, and two short," and written as “Rockridge 93R12”. (The two examples cited in this paragraph are taken directly from usage in the 1935 American film Party Wire.)[37] Again, however, it should be noted, whilst this practice was common, it was not ubiquitous, since despite giving a standard configuration for terse, easily interpreted numbers with their respective ring codes, its chief functional drawback was with the first ring always being long and the second always being short, this limited the number of brief and thus practical ringing combinations that could be used on single multiparty subscriber numbers.

Further to this functional deficiency, was a twofold practical deficiency. For though one was only to answer one's own ringing code, every party on the same subscriber line could hear all the ringing codes. This meant firstly, frequently ringing telephones were a disruptive annoyance, as each party on the line had to stop to listen every time the telephone rang in order to determine according to the ringing cadence if they were the party being called on any given ring.[38] Secondly, if any party on a given line should so be inclined, there was the insidious opportunity to listen in on other parties' calls.

More selective ringing methods were introduced using various technologies.

In the system of divided ringing, the ringing circuit was separated from the talking circuit by adding a ground connection between the central office and the subscriber stations for ringing. On the same subscriber line, one party used the tip side of the line and ground for ringing, whilst the other party on the same line used the ring wire and ground for ringing, to achieve full selectivity for two-party lines, in which only the selected station would ring. These names for the wires are derived from the paired cord plugs—used on a manual switchboard—composed of three parts: the tip and the sleeve separated by a narrow metal band called the ring, each of these three components being insulated from one another.[39] In the Bell System, the two stations were thus called the tip party and the ring party, In combination with code ringing, this method could be extended to four and eight subscribers to reduce the number of disturbances. In several variations of divided ringing, also called grounded ringing, the bells were activated with polarized current, so that full selectivity was achieved for up to four parties.

Another selective ringing system was based on using different ringing frequencies for each station on the party line. In North America, this was used mostly by independent telephone systems, while the Bell System abandoned frequency selective ringing in the early 1900s. Initially four frequencies were used, which were based on a system of harmonic multiples of a frequency of 16 2/3 Hz. Combined with divided ringing, this provided fully selective service for up to eight stations.

All fully selective ringing systems on party lines still brought the inconvenience of finding the line in use occasionally, by hearing talking, when one picked up the phone to make a call. All party lines also required special equipment to complete calls to another party on the same party line.[40]

Characteristics

In the local-battery system of the early cranked magneto phones, the phone's own battery powered its transmitter as well as the receiver of the called phone. If too many phones were off-hook and listening, the additional receivers would load down the transmitter's battery with a voltage so low that no phone could receive an intelligible signal.

With party-line service, particularly if there were more than two subscribers on the line, it was often necessary to complete a long-distance call through the operator to identify and correctly bill the calling party. In some cases, the calling party would misidentify themselves in an attempt to send the bill to another party.[41]

A two-party line split between tip party and ring party could be created in such a way as to allow the central office to determine which party placed an outbound toll call by detecting that one of the ringers was disconnected when that subscriber went off-hook. This system would fail if any provision was made to allow the subscriber to turn off the bells (do not disturb) for privacy or unplug the telephone; it also presumed that each subscriber only had one telephone connected to the line.

One variation of identifying the calling party on direct dialed long distance calls is a party code, usually a single digit inside a circle displayed on the phone's number tag. The dialing sequence for such calls is "1" (access number for DDD), the party code, the area code, and the desired number (1 + party code + area code + number).

Systems which identify the caller's name and address to emergency telephone numbers (such as Enhanced 9-1-1 in North America) may be unable to identify which of multiple parties on a shared line placed a distress call; this is aggravated by the use of old mechanical switching equipment for party lines as this obsolete apparatus consistently provides no caller ID and often also lacks automatic number identification capability.

When the party line was already in use, if any of the other subscribers to that line picked up the phone, they could hear and participate in the conversation. Eavesdropping opportunities abounded. If one of the parties used the phone heavily, then the inconvenience for the others was more than occasional, as depicted in the 1959 comedy film Pillow Talk.[42]

Mischievous teens soon discovered that calling their own number and hanging up would make all phones on the network ring, and many of the residents on the system (sometimes a half a dozen or more) would answer the phone at the same time. Party lines were typically operated using mechanical switching systems which recognized certain codes for revertive calls; these no longer work on modern electronic or digital switchgear.

Party lines are not suitable for Internet access. If one customer is using dial-up, it will jam the line for all other customers of the same party line. Bridge taps made party lines unsuitable for DSL, even in the few areas where distance from the central office did not already preclude its use. Telephone companies typically do not allow client-owned equipment to be directly connected to party lines, posing an additional obstacle to their use for data.

Railroad systems

Telephone service for dispatchers and service personnel between way stations along railways used a form of party line service for many decades starting in the early 1900s. Railroad telephone systems often consisted of several dozen way stations interconnected with a shared line that used DC voltages as high as 400 V for selective signaling to alert called stations.

Carrier systems

With the advent of sophisticated electronics in the early part of the 1900s, telephone service providers developed methods to share a single copper line to transmit multiple telephone calls simultaneously. Various pair gain methods using time-division multiplexing and frequency-division multiplexing prevented interference between simultaneous calls. A distant suburb may have a subscriber loop carrier or digital loop carrier system in which a remote concentrator is located near the subscribers to connect multiple local subscriber loops to one common line to a central office exchange. A single optical fibre can also be shared between multiple subscribers in fibre to the cabinet systems.

CATV cable modems are connected to an inherently shared medium. The signal from the shared line is split to multiple subscribers. Signals for television, and data operate at various different carrier frequencies.

Digital wireless connections, such as mobile phones or voice over IP running over rural wireless Internet infrastructure are also inherently a shared medium. Sufficiently high levels of usage of simultaneous active connections cause congestion on a mobile telephone network or impair transmission quality.

Modern usage

Party lines remain primarily in rural areas where local loops are long and private loops uneconomical when spread sparsely over a large area. Privacy is limited and congestion often occurs. In isolated communities, party lines have been used without any direct connection to the outside world.

One example of a community linked by party line is in Big Santa Anita Canyon high in the mountains above Los Angeles, near Sierra Madre, California, where 81 cabins, a group camp and a pack station all communicate by magneto-type crank phones. One ring is for the pack station, two rings for the camp and three rings means all cabins pick up.[43] The system is a single wire using the ground as a return path. The line was only partially functioning due to lack of maintenance but as of 2013 rebuilding was underway.[44]

In modern use, the term party line has occasionally been used to market conference bridge and voice bulletin board service, but these are not party lines in the original sense of the term as users call in using multiple, individual lines.

See also

References

- ↑ "Party Line – Definition of Party line by Merriam-Webster".

- ↑ "The Party Wire, the 3/22/1919 Norman Rockwell Leslie's Cover". Best-Norman-Rockwell-Art.com.

- ↑ "Telephones UK – Shared Service".

- ↑ Farley, Tom. "privateline.com's Telephone History Series" (PDF). Privateline.com. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ Subscriber Trunk Dialling Call Zones, NSW State Parliament speech, May 3, 2000

- ↑ "'Party Line' telephone exchange service". Dubuque Sunday Herald (Advertisement). April 21, 1897. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ Such a system in described in McCullough, Colleen. The Thorn Birds.

- ↑ Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph (July 10, 1942). "If you use a party-line telephone: be a good telephone neighbour". The Miami News (Advertisement).

- ↑ "Party line phones show tremendous increase in state". The Daily Times. Beaver and Rochester. April 20, 1943. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ Bell Canada (December 31, 1919). "Two-party-line telephone service". Montreal Gazette (Advertisement). Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ Peninsular Telephone Company (October 13, 1948). "Co-operation wins on the telephone party line too". St. Petersburg Times (Advertisement). Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ New York Telephone (September 26, 1946). "Sharing a party telephone line is a lot like saying 'hop in' to a neighbour". The Newburgh News (Advertisement). Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ Cindy McCleish Ingram (January 18, 2010). "Early telephone operator recalls party (line) days". New Orleans Times-Picayune. Associated Press. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Subscriber to party line telephone asks how to cope with line hog". The Virgin Islands Daily News. February 8, 1967. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Telephone party lines kept everyone abuzz". Mercer Island Reporter. November 24, 2008. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Party line helped Ole Miss hold Tennessee to 14–0". The Miami News. December 13, 1942.

- ↑ "Suspected bookie joint had city store licence, party line telephone". St. Petersburg Times. May 29, 1952. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Party line protected". The Milwaukee Journal. June 18, 1968.

- ↑ "There'll be no colour line on telephone party line in Miss". Washington Afro-American. May 1, 1956.

- ↑ "New invention ensures privacy on rural and party telephone lines". The Morning Leader. April 25, 1925.

- ↑ "New gimmick will end party line listening". Ottawa Citizen. May 9, 1955. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "A menace to the party line". Ottawa Citizen. May 14, 1955. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Convict woman who refused to yield party line". The Day. May 18, 1955. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Party line hog is found guilty". Oxnard Press-Courier. May 18, 1955. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Listening in on the party line". The Milwaukee Journal. January 23, 1959. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Party line tied up as three boys drown". The Pittsburgh Press. June 8, 1970.

- ↑ "Girl charged in not yielding phone line". The Deseret News. June 9, 1970. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Party line". Lodi News-Sentinel. June 8, 1970. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Party line pleas fail". Vancouver Sun. United Press International. June 4, 1970. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Sons drown while mum tries to get use of party line telephone". Ludington Daily News. United Press International. June 4, 1970. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Telephone party line a victim of progress". Star-News. United Press International. July 11, 1971. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ Kissel, Kelly P. (October 13, 1989). "Party line customers hang it up in rural West Virginia". Lawrence Journal-World. Associated Press. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ Mabray, D'Ann (September 6, 1992). "Death of party line may not be far off". The Victoria Advocate. p. 1.

- ↑ Cappiello, Janet L. (April 1, 1991). "It's the end of the party line in Connecticut". Record-Journal. Associated Press. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Regents' panel OKs phone proposal". The Pantagraph. Bloomington, IL. May 17, 1990..

- ↑ http://etler.com/docs/WECo/Fundamentals/files/3-LocalManual.pdf

- ↑ Party Wire (1935) Full Movie. January 11, 2015 – via YouTube.

- ↑ International Correspondence Schools (1916). "Party Line Telephones". Subscribers' Station Equipment. International Library of Technology. Scranton, PA: International Textbook Company. p. 20. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ↑ http://www.stjosephmusicfoundation.org/documents/Pinouts.pdf

- ↑ Revertive call circuit, US patent 3461246 filed July 22, 1966 by Schneider Gerhard O K of Stromberg Carlson Corp

- ↑ "Telephone company seeks 'party line pirates'". The Deseret News. June 24, 1919.

- ↑ McDonald, Tamar Jeffers (2013). Romantic Comedy: Boy Meets Girl Meets Genre. Columbia University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-231-50338-9.

- ↑ "Big Santa Anita Canyon Map & Facilities". Adam's Pack Station. Archived from the original on January 8, 2007.

- ↑ Kasten, Chris. "Rebuilding the Big Santa Anita's Crank Phone System: Living History Alongside the Chantry Flats Trails". Canyon Cartography. Canyon Cartography. Retrieved March 29, 2015.