Passport system in the Soviet Union

The passport system of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was an organizational framework of the single national civil registration system based upon identification documents, and managed in accordance with the laws by ministries and other governmental bodies authorized by the Constitution of the USSR in the sphere of internal affairs.

Prehistory: 1917–1932

The foundations of the passport system of the Russian Empire, inherited by a Russian Republic in March, 1917 for a short period of 8 months, were scattered with the October Revolution, which dismantled all the state apparatus, including police as one of the backbone elements of this system. The allegation that in the first post-revolutionary years an internal passport system did not exist at all neither in the RSFSR, nor in the USSR (established December 29, 1922),[1] is only partially true: old passports were not made null and void in the function of an identification tool. However, by 1917 a known part of the adult population had no passports at all: many peasants, soldiers and officers, prisoners, etc.

Personal Identification

"Metrika" (Russian: метрика), an excerpt from the birth registration books (Russian: Метрическая книга) was a kind of identity document available to everybody.

On December 18, 1917 the Sovnarkom issued the decree[2] which laid the legal and institutional framework for the organization of registration and statistics of the three major type of life events: birth, marriage/divorce, and death. Once run by the church, all this paperwork was transferred to the state authorities.

As it was before the revolution, the "metriks" records (both in the books and in the excerpts given to the parents) contained such critical identification parameters as: date and place of birth, name and sex of a child, full names of his parents (if known). By default, a child inherited a surname of its father (if known), mother (if single); however both parents were not limited in their choice. Unlike the pre-revolutionary "metriks", civilian documents of new Soviet authorities said nothing of parents' religion. Also, due to the non-clerical status of the birth registration, an information about "vospriemniki" (godfather and godmother) also disappeared from this document.

The system originates in the Decree of the VTsIK and RSFSR Sovnarkom About Personal Identity Cards issued on June 20, 1923, which abolished all previously-existing travel and residence permit documents (but allowed various documents for personal identification). Urban population had to obtain ID cards at the local militsiya departments, rural residents were serviced by volost ispolkoms (executive governmental offices). The ID cards were valid for three years. They could have a photo pasted on. Neither photos nor ID cards were obligatory. The system of residential registration existed, but any personal documents were valid for this purpose and the registration, although known as "propiska" was not associated with the residential permit of the later propiska system.

The Small Soviet Encyclopedia released in May 1930 seems to be the last encyclopedical source which fixed the early post-revolutionary nihilistic treatment of the passport system as a tool of the so-called "police state" where it provides "police supervision and taxation system". Stating that the whole concept of the "passport system" is unknown to the Soviet system of rights, the author insists that the passport system is also burdensome to the contemporary bourgeois (i.e. non-socialist) states which tend to simplify or even abolish this system.[3]

History: 1932–1991

On December 27, 1932 the USSR Central Executive Committee and Sovnarkom issued a decree About establishment of the Unified Passport System within the USSR and the Obligatory Propiska of Passports. The declared purposes were the improvement of population bookkeeping in various urban settlements and "the removal of persons not engaged in industrial or other socially-useful work from towns and cleansing of towns from hiding kulaks, criminals and other antisocial elements. "Hiding kulaks" was an indication at fugitive peasants who tried to run away from the collectivization. "Removal" usually resulted in some form of forced labour.

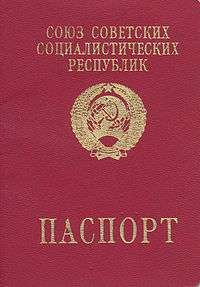

Passports were introduced for urban residents, sovkhozniks and workers of novostroykas (новостройка, a major construction site of a new town, plant, railway station, etc.). It should be noted that according to the 1926 Soviet Census 82% of population in the Soviet Union was rural. Kolkhozniks and individual peasants did not have passports and could not move into towns without permission. Permissions were given by chairpersons of collective farms or rural councils. Repeated violation of the passport regime was a criminal offence. Passports were issued by the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs (Soviet law enforcement) and until the 1970s had a green cover.

The implementation of the passport system was based on the USSR Sovnarkom decree dated April 22, 1933 About the Issue of Passports to the USSR Citizens in the territory of the USSR. The document declared that all citizens at least sixteen years old residing in cites, towns, and urban workers' settlements, as well as residing within one hundred kilometres of Moscow and Leningrad, within fifty kilometres of Kharkov, Kiev, Minsk, Rostov-on-Don and Vladivostok and within the hundred-kilometre zone along the Western border of the USSR were required to have a passport with propiska. Within these territories passports were the only valid personal identification document. Since 1937 all passports had a photo headshot of its owner.

On September 10, 1940 the USSR Sovnarkom decreed the Passport Statute (Russian: Положение о паспортах, Položenye o pasportakh). It provisioned a special treatment of propiska in capital cities of republics, krais, and oblasts, in state border areas and at important railroad junctions.

On October 21, 1953 the USSR Council of Ministers decreed the new Passport Statute. It made passports obligatory for all citizens older than sixteen years in all non-rural settlements. Rural residents could not leave their place of residence for more than thirty days, and even for this leave a permit from a selsoviet was required. The notion of "temporary propiska" was introduced, in addition to the regular or "permanent" one. A temporary propiska was issued for work-related reasons and for study away from home.

Since the First Congress of Collective Farms Workers in the summer of 1969, the Council of Ministers of the USSR relieved the rural residents from procedural difficulties in obtaining the Soviet passport.

On August 28, 1974 the USSR Council of Ministers issued a new Statute of the Passport System in the USSR and new rules of propiska. The latter rules were in effect until October 23, 1995. However the "blanket passportisation" was started only in 1976 and finished in 1981.

See also

Further reading

- Борисенко В. Паспортная система в России: история и современность [The Passport System in Russia: History and Modernity] (doc) (in Russian).

- Развитие паспортной системы в условиях укрепления административно-командной системы в СССР… [Development of the Passport System…] (in Russian). Sverdlovsk Regional Office of the Federal Migration service of the Russian Federation (MIA).

- Dzhuvaha, V. (28 March 2008). Безпаспортне кріпацтво [Passportless serfdom] (in Ukrainian). Tyzhden. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

References

- ↑ Борисенко В. Паспортная система в России: история и современность [The Passport System in Russia: History and Modernity] (doc) (in Russian).

- ↑ Декрет ВЦИК, СНК РСФСР от 18 декабря 1917. О гражданском браке, о детях и о ведении книг актов состояния [On civil marriage, on children, and on the book registration of acts of civil status] (in Russian). СУ РСФСР. — 1917. — № 11. — ст. 160.

- ↑ Паспорт [Passport]. Малая Советская Энциклопедия (in Russian). т. 6. (1 ed.). М.: Акционерное общество „Советская Энциклопедия”. 1930 [April 30, 1930]. col.342–343.

Паспортная система была важнейшим орудием полицейского воздействия и податной политики в т.н. «полицейском государстве»… Особо тягостная для трудовых масс, паспортная система стеснительна и для гражданского общества буржуазного гос-ва, к-рое упраздняет или ослабляет её. Советское право не знает паспортной системы.