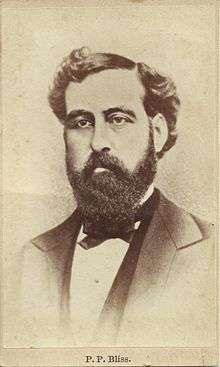

Philip Bliss

Philip Paul Bliss (9 July 1838 – 29 December 1876) was an American composer, conductor, writer of hymns and a bass-baritone[1] Gospel singer. He wrote many well-known hymns, including Almost Persuaded; Hallelujah, What a Saviour!; Let the Lower Lights Be Burning; Wonderful Words of Life and the tune for Horatio Spafford's It Is Well with My Soul.

Bliss's house in Rome, Pennsylvania is now operated as the Philip P. Bliss Gospel Songwriters Museum.

Early life

Bliss was born in Clearfield County, Pennsylvania (although possibly in Rome, PA) in a log cabin. His father was Mr. Isaac Bliss, a practicing Methodist, who taught the family to pray daily. Isaac loved music and allowed Philip to develop his passion for singing.

When he was a boy, Bliss’s family moved to Kinsman, Ohio in 1844, and then returned to Pennsylvania in 1847, settling first in Espeyville, Crawford County, and a year later in Tioga County.[2] Bliss had little formal education and was taught by his mother, from the Bible.

At age 10, while selling vegetables to help support the family, Bliss first heard a piano. At age 11, he left home to make his own living. He worked in timber camps and sawmills. While working, he irregularly went to school to further his education.

Teaching

At 17, Bliss finished his requirements to teach. The next year, in 1856, he became a schoolmaster at Hartsville, New York, and during the summer he worked on a farm.

In 1857, Bliss met J. G. Towner, who taught singing. Towner recognised Bliss’s talent and gave him his first formal voice training. He also met William B. Bradbury, who persuaded him to become a music teacher. His first musical composition was sold for a flute. In 1858, he took up an appointment in Rome Academy, Pennsylvania.

In 1858, in Rome, Bliss met Lucy J. Young, whom he married on June 1, 1859. She came from a musical family and encouraged the development of his talent. She was a Presbyterian, and Bliss joined her Church.

At age 22, Bliss became an itinerant music teacher. On horseback, he went from community to community accompanied by a melodeon. Bliss’s wife’s grandmother lent Bliss $30 so he could attend the Normal Academy of Music of New York for six weeks. Bliss was now recognised as an expert within his local area. He continued the itinerant teaching.

At this time he turned to composition. None of his songs were ever copyrighted.

Evangelist

In 1864, the Blisses moved to Chicago. Bliss was then 26. He became known as a singer and teacher. He wrote a number of Gospel songs. Bliss was paid $100 for a concert tour which lasted only a fortnight. He was amazed so much money could be earned so quickly. The following week, he was drafted for service in the Union Army. Because the war was almost over, his notice was canceled after a few weeks. The unit he served with was the 149th Pennsylvania Infantry.

Following this, Bliss went on another concert tour, but this failed. He was, however, offered a position at Root and Cady Musical Publishers, at a salary of $150 per month. Bliss worked with this company from 1865 until 1873. He conducted musical conventions, singing schools and concerts for his employers. He continued to compose hymns, which were often printed in his employer’s books.

In 1869, Bliss formed an association with Dwight L. Moody. Moody and others urged him to give up his job and become a missionary singer. In 1874, Bliss decided he was called to the task of “winning souls”. He then became a full-time evangelist. Bliss made significant amounts of money from royalties and gave them to charity and to support his evangelical endeavours.

Bliss wrote the gospel song "Hold the Fort" after hearing Major Daniel Webster Whittle narrate an experience in the American Civil War.[3]

Death

On 29 December 1876, the Pacific Express train on which Bliss and his wife were traveling in approached Ashtabula, Ohio. While the train was in the process of crossing a trestle bridge, which collapsed, all the carriages fell into the ravine below. Bliss escaped from the wreck, but the carriages caught fire and Bliss returned to try to extricate his wife. No trace of either body was discovered. Ninety-two of the 159 passengers are believed to have died in what became known as the Ashtabula River Railroad Disaster.

The Blisses were survived by their two sons, George and Philip Paul, then aged four and one, respectively.

A monument to Bliss was erected in Rome, Pennsylvania.

Found in his trunk, which somehow survived the crash and fire, was a manuscript bearing the lyrics of the only well-known Bliss Gospel song for which he did not write a tune. Soon thereafter, set to a tune specially written for it by James McGranahan, it became one of the first songs recorded by Thomas Alva Edison, that song being I Will Sing of My Redeemer.[4]

Works

According to the Philip P. Bliss Gospel Songwriters Museum, the books of songs by Philip P. Bliss are as follows: The Charm (1871); The Song Tree, a collection of parlor and concert music (1872); The Sunshine for Sunday Schools (1873); The Joy for conventions and for church choir music (1873); and Gospel Songs for Gospel meetings and Sunday schools (1874). All of these books were copyrighted by John Church and Co.

In addition to these publications, in 1875, Bliss compiled, and in connection with Ira D. Sankey, edited Gospel Hymns and Sacred Songs. In 1876, his last work was the preparation of the book known as Gospel Hymns No. 2, Sankey being associated with him as editor. These last two books are published by John Church and Co. and Biglow and Main jointly - the work of Mr. Bliss in them, under the copyright of John Church and Co.

Many of his pieces appear in the books of George F. Root and Horatio R. Palmer, and many were published in sheet music form. A large number of his popular pieces were published in The Prize, a book of Sunday school songs edited by Root in 1870.

Connection to Titanic

Survivors of the RMS Titanic disaster, including Dr. Washington Dodge, reported that passengers in lifeboats sang the Bliss hymn "Pull For The Shore", some while rowing. During a May 11, 1912 luncheon talk at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco, just a few weeks after his family and he survived the sinking of the ocean liner, Dodge recounted:

"Watching the vessel closely, it was seen from time to time that this submergence forward was increasing. No one in our boat, however, had any idea that the ship was in any danger of sinking. In spite of the intense cold, a cheerful atmosphere pervaded those present, and they indulged from time to time in jesting and even singing `Pull for (the) Shore' ..."

See also

- Ninde, Edward S.; The Story of the American Hymn, New York: Abingdon Press, 1921.

- Wells, Amos R.; A Treasure of Hymns, Boston: United Society of Christian Endeavour, 1914

Notes

- ↑ The Heart of a Hymn writer, Masters Peter; Men of Purpose, Wakeman Publishers Ltd,London,1973 ISBN 978-1-870855-41-9

- ↑ Whittle, Daniel Webster (1877). Memoirs of Philip P. Bliss. Chicago: A. S. Barnes & Company. p. 17. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- ↑ "D. W. Whittle". Bible Study Tools. Retrieved 2012-07-18.

- ↑ McCann, Forrest M. (1997). Hymns and History: An Annotated Survey of Sources. Abilene, TX: ACU Press. Pp. 154, 359-360. ISBN 0-89112-058-0

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Philip Paul Bliss |

- Spafford Hymn Manuscript Peace Like a River / It is Well with my Soul - as originally penned by Horatio Spafford

- Christian Biography Resources

- The Memoirs of PP Bliss

- Bliss Photo & Disaster Monument

- The Music of Philip Paul Bliss

- Philip P. Bliss Gospel Songwriters Museum

- Free scores Mutopia Project

- Works by or about Philip Bliss at Internet Archive