Philosopher

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

|

| Philosophers |

| Traditions |

| Periods |

| Literature |

|

| Branches |

| Lists |

| Miscellaneous |

|

|

A philosopher is someone who practices philosophy, which involves rational inquiry into areas that are outside of either theology or science.[1] The term "philosopher" comes from the Ancient Greek φιλόσοφος (philosophos) meaning "lover of wisdom". The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek thinker Pythagoras.[2]

In the classical sense, a philosopher was someone who lived according to a certain way of life, focusing on resolving existential questions about the human condition, and not someone who discourses upon theories or comments upon authors.[3] Typically, these particular brands of philosophy are Hellenistic ones and those who most arduously commit themselves to this lifestyle may be considered philosophers.

In a modern sense, a philosopher is an intellectual who has contributed in one or more branches of philosophy, such as aesthetics, ethics, epistemology, logic, metaphysics, social theory, and political philosophy. A philosopher may also be one who worked in the humanities or other sciences which have since split from philosophy proper over the centuries, such as the arts, history, economics, sociology, psychology, linguistics, anthropology, theology, and politics.[4]

History

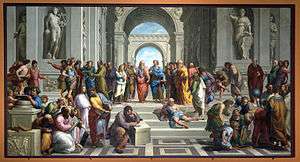

Ancient Greece and Rome

The separation of philosophy and science from theology began in Greece during the 6th century BC.[5] Thales, an astronomer and mathematician, was considered by Aristotle to be the first philosopher of the Greek tradition.[6]

While Pythagoras coined the word, the first known elaboration on the topic was conducted by Plato. In his Symposium, he concludes that Love is that which lacks the object it seeks. Therefore, the philosopher is one who seeks wisdom; if he attains wisdom, he would be a sage. Therefore, the philosopher in antiquity was one who lives in the constant pursuit of wisdom, and living in accordance to that wisdom.[7] Disagreements arose as to what living philosophically entailed. These disagreements gave rise to different Hellenistic schools of philosophy. In consequence, the ancient philosopher thought in a tradition.[8] As the ancient world became schism by philosophical debate, the competition lay in living in manner that would transform his whole way of living in the world.[9]

Among the last of these philosophers was Marcus Aurelius, who is widely regarded as a philosopher in the modern sense, but personally refused to call himself by such a title, since he had a duty to live as an emperor.[10]

Transition

According to the Classicist Pierre Hadot, the modern conception of a philosopher and philosophy developed predominately through three changes:

The first is the natural inclination of the philosophical mind. Philosophy is a tempting discipline which can easily carry away the individual in analyzing the universe and abstract theory.[11]

The second is the historical change through the Medieval era. With the rise of Christianity, the philosophical way of life was adopted by its theology. Thus, philosophy was divided between a way of life and the conceptual, logical, physical and metaphysical materials to justify that way of life. Philosophy was then the servant to theology.[12]

The third is the sociological need with the development of the university. The modern university requires professionals to teach. Maintaining itself requires teaching future professionals to replace the current faculty. Therefore, the discipline degrades into a technical language reserved for specialists, completely eschewing its original conception as a way of life.[12]

Medieval era

In the fourth century, the word philosopher began to designate a man or woman who led a monastic life. Gregory of Nyssa, for example, describes how his sister Macrina persuaded their mother to forsake "the distractions of material life" for a life of philosophy.[13]

Later during the Middle Ages, persons who engaged with alchemy was called a philosopher - thus, the Philosopher's Stone.[14]

Early Modern era

| “ | Generally speaking, university philosophy is mere fencing in front of a mirror. In the last analysis, its goal is to give students opinions which are to the liking of the minister who hands out the Chairs... As a result, this state-financed philosophy makes a joke of philosophy. And yet, if there is one thing desirable in this world, it is to see a ray of light fall onto the darkness of our lives, shedding some kind of light on the mysterious enigma of our existence. | ” |

| — Arthur Schopenhauer | ||

Many philosophers still emerged from the Classical tradition, as saw their philosophy as a way of life. Among the most notable are René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, Nicolas Malebranche, and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. With the rise of the university, the modern conception of philosophy became more prominent. Many of the esteemed philosophers of the eighteenth century and onward have attended, taught, and developed their works in university. Early examples include: Immanuel Kant, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.[15]

After these individuals, the Classical conception had all but died with the exceptions of Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche. The last considerable figure in philosophy to not have followed a strict and orthodox academic regime was Ludwig Wittgenstein.[16]

Modern academia

In the modern era, those attaining advanced degrees in philosophy often choose to stay in careers within the educational system. According to a 1993 study by the National Research Council (as reported by the American Philosophical Association), 77.1% of the 7,900 holders of a Ph.D. in philosophy who responded were employed in educational institutions (academia). Outside of academia, philosophers may employ their writing and reasoning skills in other careers, such as medicine, bioethics, business, publishing, free-lance writing, media, and law.[17]

Prizes in philosophy

Various prizes in philosophy exist. Among the most prominent are:

Certain esteemed philosophers, such as Henri Bergson, Bertrand Russell, Albert Camus, and Jean-Paul Sartre, have also won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The John W. Kluge Prize for the Study of Humanity, created by the Library of Congress to recognize work not covered by the Nobel Prizes, was given to philosophers Leszek Kołakowski in 2003, Paul Ricoeur in 2004, and Jürgen Habermas and Charles Taylor in 2015.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ Russell, Bertrand (1946). A History of Western Philosophy. Great Britain: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. p. 10. Retrieved 31 March 2016 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ φιλόσοφος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ↑ Pierre Hadot, The Inner Citadel. pg. 4

- ↑ Shook, John R., ed. (2010). Dictionary of Modern American philosophers (online ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. Introduction. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199754663.001.0001. ISBN 9780199754663. OCLC 686766412. (subscription required (help)).

The label of “philosopher” has been broadly applied in this Dictionary to intellectuals who have made philosophical contributions regardless of academic career or professional title. The wide scope of philosophical activity across the time-span of this Dictionary would now be classed among the various humanities and social sciences which gradually separated from philosophy over the last one hundred and fifty years. Many figures included were not academic philosophers but did work at the philosophical foundations of such fields as pedagogy, rhetoric, the arts, history, politics, economics, sociology, psychology, linguistics, anthropology, religion, and theology. Philosophy proper is heavily represented, of course, encompassing the traditional areas of metaphysics, ontology, epistemology, logic, ethics, social/political theory, and aesthetics, along with the narrower fields of philosophy of science, philosophy of mind, philosophy of language, philosophy of law, applied ethics, philosophy of religion, and so forth

- ↑ Russell, Bertrand (1946). A History of Western Philosophy. Great Britain: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. p. 11. Retrieved 31 March 2016 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Aristotle, Metaphysics Alpha, 983b18.

- ↑ That is to say philosophically - Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life, trans. Michael Chase. Blackwell Publishing, 1995. pg. 27: Introduction: Pierre Hadot and the Spiritual Phenomenon of Ancient Philosophy by Arnold I. Davidson. Citing Hadot, 'Presentation au College International de Philosophie,' p. 4.

- ↑ Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life, trans. Michael Chase. Blackwell Publishing, 1995. pg. 5: Introduction: Pierre Hadot and the Spiritual Phenomenon of Ancient Philosophy by Arnold I. Davidson. Citing Hadot, 'Theologie, exegese, revelation' p. 22

- ↑ Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life, trans. Michael Chase. Blackwell Publishing, 1995. pg. 30: Introduction: Pierre Hadot and the Spiritual Phenomenon of Ancient Philosophy by Arnold I. Davidson. Citing Hadot, Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques, p. 13

- ↑ Wikisource:Meditations#THE EIGHTH BOOK

- ↑ Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life, trans. Michael Chase. Blackwell Publishing, 1995. pg. 31: Introduction: Pierre Hadot and the Spiritual Phenomenon of Ancient Philosophy by Arnold I. Davidson. Citing Hadot, 'Presentation au College International de Philosophie,' p.7

- 1 2 Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life, trans. Michael Chase. Blackwell Publishing, 1995. pg. 32: Introduction: Pierre Hadot and the Spiritual Phenomenon of Ancient Philosophy by Arnold I. Davidson.

- ↑ Readings in World Christian History (2013), p. 147, 149

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". etymonline.com.

- ↑ Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life, trans. Michael Chase. Blackwell Publishing, 1995. pg. 271: Philosophy as a Way of Life

- ↑ A. C. Grayling. Wittgenstein: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2001. pg. 15

- ↑ APA Committee on Non-Academic Careers (June 1999). "A non-academic career?" (3rd ed.). American Philosophical Association. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ↑ Schuessler, Jennifer (11 August 2015). "Philosophers to Share $1.5 Million Kluge Prize". New York Times. p. C3(L). Retrieved 6 April 2016.