Piano Concerto No. 24 (Mozart)

| Piano Concerto No. 24 | |

|---|---|

| by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | |

| |

| Key | C minor |

| Catalogue |

|

| Genre | Concerto |

| Style | Classical |

| Composed | 1786 |

| Published | 1800 |

| Movements | Three (Allegro, Larghetto, Allegretto) |

| Scoring | Piano and orchestra |

The Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K. 491, is a concerto for keyboard (usually a piano or fortepiano) and orchestra composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart composed the concerto in the winter of 1785–1786, finishing it on 24 March 1786, three weeks after the completion of the Piano Concerto No. 23 (K. 488) in A major. He premiered the work in early April 1786 at the Burgtheater in Vienna.

The work is one of only two minor-key piano concertos that Mozart composed, the other being the No. 20 (K. 466) in D Minor. None of Mozart's other piano concertos features a larger array of instruments: the work is scored for strings, woodwinds, horns, trumpets and timpani. The concerto consists of three movements. The first, Allegro, is in sonata form and is the longest opening movement for a concerto that Mozart had hitherto composed. The second movement, Larghetto, is in the relative major of E flat and features a strikingly simple principal theme. The final movement, Allegretto, returns to the home key of C minor and presents a theme followed by eight variations.

The work is one of Mozart's most advanced compositions in the concerto genre. Its early admirers included Ludwig van Beethoven and Johannes Brahms. Musicologist Arthur Hutchings considered it to be Mozart's greatest piano concerto.

Background

Mozart composed the concerto in the winter of 1785-86, during his fourth season in Vienna. It was the third in a set of three concertos composed in quick succession, the others being No. 22 (K. 482) in E-flat major and No. 23 (K. 488) in A major. Mozart finished composing the No. 24 shortly before the premiere of The Marriage of Figaro; the two works are assigned adjacent numbers of 491 and 492 in the Köchel catalogue.[1] While composed at the same time, the two works contrast greatly: the opera is almost entirely in major keys while the concerto is one of Mozart's few minor-key works.[2] The pianist and musicologist Robert D. Levin suggests that the concerto may have served as an outlet for a darker aspect of Mozart's creativity at the time he was composing the comic opera.[3] The premiere of the concerto was either on 3 or 7 April 1786 at the Burgtheater in Vienna; Mozart would have featured as the soloist and conducted the orchestra from the keyboard.[n 1]

In 1800, Mozart's widow Constanze sold the original score of the work to the publisher Johann Anton André of Offenbach am Main. It passed through a number of private hands during the nineteenth century before Sir George Donaldson, a Scottish philanthropist, donated it to the Royal College of Music in 1894. The College still houses the manuscript today.[9] The original score contains no tempo markings; the tempo for each movement is known only from the entries Mozart made into his catalogue.[10] The orchestral parts in the original score are written in a clear manner.[11] The solo part, on the other hand, is often incomplete, due to Mozart notating only the outer parts of passages of scales or broken chords. This suggests that Mozart improvised much of the solo part when performing the work.[12] The score also contains a number of late additions, including that of the second subject of the first movement's orchestral exposition.[13] There is the occasional notation error in the score, which musicologist Friedrich Blume attributed to Mozart having "obviously written in great haste and under internal strain".[14]

Overview

The concerto is divided into the following three movements:

- Allegro in C minor (3/4 time)

- Larghetto in E-flat major (cut common time)

- Allegretto (Variations) in C minor (cut common time)

The concerto is scored for one flute, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani and strings.[15] This amounts to the largest orchestra for which Mozart composed any of his concertos.[16] It is the only one of two of Mozart's piano concertos that is scored for both oboes and clarinets (the other one, his concerto for two pianos, only has clarinets in the revised version). Robert D. Levin writes: "The richness of wind sonority, due to the inclusion of oboes and clarinets, is the central timbral characteristic of [the concerto]: time and again in all three movements the winds push the strings completely to the side."[17] The solo instrument for the concerto is scored as a "cembalo". This term often denotes a harpsichord, but in this concerto, Mozart used it as a generic term that encompassed the fortepiano.[18]

First movement

The first movement is longer and more complex than any that Mozart had hitherto composed in the concerto genre.[19] It is in 3/4 time; among Mozart's piano concertos, No. 11 in F major and No. 14 in E-flat major are the only others to commence in triple metre.[20]

The first movement follows the standard outline of a sonata form concerto movement of the Classical period. It begins with an orchestral exposition, which is followed by a solo exposition, a development section, a recapitulation, a cadenza and a coda. Within this conventional outline, Mozart engages in extensive structural innovation.[21]

Exposition

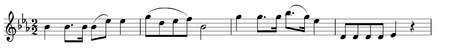

The orchestral exposition, 99 measures long, presents two groups of thematic material, one primary and one secondary, both in the tonic of C minor.[22] The orchestra opens the principal theme in unison, but not powerfully: the dynamic marking is piano.[23] The theme is tonally ambiguous, not asserting the home key of C minor until its final cadence in the thirteenth measure.[24] It is also highly chromatic: in its 13 measures it utilises all 12 notes of the chromatic scale.[25]

The solo exposition follows its orchestral counterpart, and it is here that convention is discarded from the outset: the piano does not enter with the principal theme. Instead, it has an 18-measure solo passage. It is only after this passage that the principal theme appears, carried by the orchestra. The piano then picks up the theme from its seventh measure.[26] Another departure from convention is that the solo exposition does not re-state the secondary theme from the orchestral exposition. Instead, a succession of new secondary thematic material appears. Musicologist Donald Tovey considered this introduction of new material to be “utterly subversive of the doctrine that the function of the opening tutti [the orchestral exposition] was to predict what the solo had to say.”[27]

One hundred measures into the solo exposition, which is now in the relative major of E-flat, the piano plays a cadential trill, leading the orchestra from the dominant seventh to the tonic. This suggests to the listener that the solo exposition has reached an end, but Mozart instead gives the woodwinds a new theme. The exposition continues for another 60 or so measures, before another cadential trill brings about the real conclusion, prompting a ritornello that connects the exposition with the development. The pianist and musicologist Charles Rosen argues that Mozart thus created a "double exposition". Rosen also suggests that this explains why Mozart made substantial elongations to the orchestral exposition during the composition process; he needed a longer orchestral exposition to balance its "double" solo counterpart.[28]

Development

The development begins with the piano repeating its entry to the solo exposition, this time in the relative major of E flat. The Concerto No. 20 is the only other of Mozart's concertos in which the solo exposition and the development commence with the same material. In the Concerto No. 24, the material unfolds in the development in a manner different from the solo exposition: the opening solo motif, with its half cadence, is repeated four times, with one intervention from the woodwinds, as if asking question after question. The final question is asked in C minor, and is answered by a descending scale from the piano that leads to an orchestral statement, in F minor, of the movement's principal theme.[29] The orchestral theme is then developed: the motif of the theme's fourth and fifth measures descends through the circle of fifths, accompanied by an elaborate piano figuration. After this, the development proceeds to a stormy exchange between the piano and the orchestra, which the twentieth-century Mozart scholar Cuthbert Girdlestone describes as "one of the few [occasions] in Mozart where passion seems really unchained",[30] and which Tovey describes as a passage of "fine, severe massiveness".[31] The exchange resolves to a passage in which the piano plays a treble line of sixteenth notes, over which the winds add echoes of the main theme. This transitional passage ultimately modulates to the home key of C minor, bringing about the start of the recapitulation with the conventional re-statement, by the orchestra, of the movement's principal theme.[32]

Recapitulation, cadenza and coda

The wide range of thematic material presented in the orchestral and solo expositions poses a challenge for the recapitulation. Mozart manages to recapitulate all of the themes in the home key of C minor. The themes are necessarily compressed, presented in a different order and with few virtuosic moments for the soloist.[33][34] The last theme to be recapitulated is the secondary theme of the orchestral exposition, which has not been heard for some 400 measures and is now adorned by a passage of triplets from the piano. The recapitulation concludes with the piano playing arpeggiated sixteenths before a cadential trill leads into a ritornello. The ritornello in turn leads into a fermata that prompts the soloist's cadenza.[35]

Mozart did not write down a cadenza for the movement, or at least there is no evidence of him having done so.[36] The lack of a Mozart cadenza led many 19th-century composers and performers, including Johannes Brahms, to write their own.[37] Uniquely among Mozart's concertos, the score does not direct the soloist to end the cadenza with a cadential trill. The omission of the customary trill is likely to have been deliberate, with Mozart choosing to have the cadenza connect directly to the coda without one.[38]

The conventional Mozartian coda would have seen the soloist with hands in lap (or perhaps conducting) while an orchestral tutti concluded the movement. In this movement, Mozart breaks with convention: the soloist interrupts the tutti with a virtuosic passage of sixteenth notes, and accompanies the orchestra through to the final pianissimo chords. These chords bring an end to the movement in the concerto's home key of C minor.[39][40]

Second movement

Alfred Einstein, writing in 1962, said of the concerto's second movement that it "moves in regions of the purest and most moving tranquility, and has a transcendent simplicity of expression".[42] Marked Larghetto, the movement is in E-flat major and cut common time. The trumpets and timpani play no part in the movement; they return for the third movement.[43]

The movement opens with the soloist playing the four-measure principal theme alone; it is then repeated by the orchestra. This theme is, in the words of Michael Steinberg, one of "extreme simplicity".[44] This was not always the case: Mozart's first sketch of the movement was much more complex. Mozart likely simplified the theme to provide a greater contrast with the dark intensity of the first movement.[45] After the orchestra repeats the principal theme there is a very simple four-measure bridge passage that Girdlestone calls to be ornamented by the soloist, arguing that "to play it as printed is to betray the memory of Mozart".[46][n 2] Following the bridge passage, the soloist plays the initial four-measure theme for a second time, before the orchestra commences a new section of the movement, in C minor. A brief return of the principal theme, its rhythm altered,[48] separates the C minor section from a section in A-flat major.[49] After the A-flat major section, the principal theme returns to mark the end of the movement, its rhythm altered yet again.[50] Now, the theme is played twice by the soloist, the two appearances being connected by the same simple four-measure bridge passage from the beginning of the movement. Girdlestone argues that here "the soloist will have to draw on his imagination to adorn [the simple bridge passage] a second time".[51] The overall structure of the movement is thus ABACA. The use of a recurring principal theme ("A", in E-flat major) and two secondary sections ("B", in C minor, and "C", in A-flat major) makes the movement characterisable as being in rondo form.[52]

In the middle statement of the principal theme (between the C minor and A-flat major sections) there is a notational error which, in a literal performance of the score, causes a harmonic clash between the piano and the winds. Mozart probably wrote the piano and wind parts at different times, resulting in an oversight by the composer.[53] Alfred Brendel, who has recorded the concerto on multiple occasions, argues that performers should not follow the score literally but correct Mozart's error. Brendel further argues that the time signature for the whole movement is a notational error: played in cut common time, the movement is, in his view, too fast.[54]

Third movement

The third movement features eight variations on a C-minor theme.[55] Hutchings considered it "both Mozart's finest essay in variation form and also his best concerto finale."[56]

The tempo marking for the movement is "Allegretto". Rosen opines that this calls for a march-like speed and argues that the movement is "generally taken too fast under the delusion that a quick tempo will give it a power commensurate with that of the opening movement."[57] Pianist Angela Hewitt sees in the movement not a march but a "sinister dance".[8]

The movement opens with the first violins stating the theme over a string and wind accompaniment. This theme consists of two eight-measure phrases, each repeated: the first phrase modulates from C minor to the dominant, G minor; the second phrase modulates back to C minor.[58] The soloist does not play any part in the statement of the theme, entering only in Variation I. Here, the piano ornaments the theme over an austere string accompaniment.[59]

Variations II to VI are what Girdlestone and Hutchings separately describe as "double" variations. Within each variation, each of the eight-measure phrases from the theme is further varied upon its repeat (AXAYBXBY).[60][61][n 3] Variations IV and VI are in major keys. Tovey refers to the former (in A-flat) as "cheerful" and the latter (in C) as "graceful".[62] Between the two major-key variations, Variation V returns to C minor; Girdlestone describes this variation as "one of the most moving".[63] Variation VII is half the length of the preceding variations, as it omits the repeat of each eight-measure phrase.[64] This variation concludes with an extra three-measure passage that culminates in a dominant chord, announcing the arrival of a cadenza.[65]

After the cadenza, the soloist opens the eighth and final variation alone, with the orchestra joining after 19 measures. The arrival of the final variation also brings a change in metre: from cut common time to compound duple time.[66] The final variation and the coda which follows both contain numerous neapolitan-sixth chords (which, in C minor, are composed of F, A-flat and D-flat). Girdlestone referred to the "haunting" effect of these chords and stated that the coda ultimately "proclaims with desperation the triumph of the minor mode".[67]

Critical reception

Ludwig van Beethoven admired the concerto and it may have influenced his Piano Concerto No. 3, also in C minor.[68][69] After hearing the work in a rehearsal, Beethoven reportedly remarked to a colleague that "[w]e shall never be able to do anything like that."[70][71] Johannes Brahms also admired the concerto, encouraging Clara Schumann to play it and writing his own cadenza for the first movement.[72] Brahms referred to the work as a "masterpiece of art and full of inspired ideas."[73]

Among modern and twentieth-century scholars, Girdlestone states that the concerto "is in all respects one of [Mozart's] greatest; we would fain say: the greatest, were it not impossible to choose between four of five of them."[74] Referring to the "dark, tragic and passionate" nature of the concerto, Einstein states that "it is hard to imagine the expression on the faces of the Viennese public" when Mozart premiered the work.[75] Musicologist Simon P. Keefe, in an exegesis of all of Mozart's piano concertos, writes that the No. 24 is "a climactic and culminating work in Mozart's piano concerto oeuvre, firmly linked to its predecessors, yet decisively transcending them at the same time."[76] The verdict of the Mozart scholar Alexander Hyatt King is that the concerto is "not only the most sublime of the whole series but also one of the greatest pianoforte concertos ever composed".[77] Arthur Hutchings's view is that "[w]hatever value we put upon any single movement from the Mozart concertos, we shall find no work greater as a concerto than this K. 491, for Mozart never wrote a work whose parts were so surely those of 'one stupendous whole'."[78]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- ↑ Some sources state that the premiere was on 3 April;[4][5] others suggest that it may have been on 7 April.[6][7][8]

- ↑ Tovey similarly acknowledges that the soloist may need to add ornamentation to the written-out part. However, Tovey cautions against taking ornamentation too far, stating that "one is thankful [for the soloist] to do as little as possible; for any deviation from Mozart's style, even a deviation into early Beethoven, sets one's teeth on edge."[47]

- ↑ The use by Girdlestone and Hutchings of the description "double" variations should not be confused with the double variation form often used by Joseph Haydn for the form of a whole movement (ABA1B1).

References

- ↑ Kerman, p. 166

- ↑ Steinberg, p. 312

- ↑ Levin, Robert D. "Piano Concerto in C minor, K, 491, annotated original score: Introduction" (PDF). www.baerenreiter.com. Bärenreiter.

- ↑ Steinberg, p. 312

- ↑ Irving, p. 238

- ↑ Levin, p. 380

- ↑ Keller, James M. "Mozart: Concerto No. 24 in C Minor for Piano and Orchestra, K. 491". San Francisco Symphony Orchestra.

- 1 2 Hewitt, Angela. "Piano Concerto No 24 in C minor, K491". Hyperion Records.

- ↑ Lawson, Colin. "Piano Concerto in C minor, K, 491, annotated original score: Preface" (PDF). www.baerenreiter.com. Bärenreiter.

- ↑ Steinberg, p. 312

- ↑ Levin, p. 380

- ↑ Mishkin. p. 352

- ↑ Mishkin, pp. 354-356

- ↑ Blume, p. 231

- ↑ Steinberg, p. 312

- ↑ Hutchings, p. 170

- ↑ Levin, p. 380

- ↑ Libin, p. 17

- ↑ Keefe (2003), p. 87

- ↑ Steinberg, p. 312

- ↑ Lindeman, p. 298

- ↑ Lindeman, p. 298

- ↑ Wen, p. 108

- ↑ Levin, pp. 380-381

- ↑ Steinberg, p. 312

- ↑ Tovey, p. 43

- ↑ Tovey, p. 43

- ↑ Rosen, pp. 245-246

- ↑ Girdlestone, pp. 395-396

- ↑ Girdlestone, p. 396

- ↑ Tovey, p. 43

- ↑ Girdlestone, p. 396

- ↑ Rosen, pp. 249-250

- ↑ Girdlestone, pp. 398-399

- ↑ Girdlestone, pp. 399-400

- ↑ Tovey, p. 45

- ↑ Bribitzer-Stull, p. 234

- ↑ Kerman, pp. 164-165

- ↑ Rosen, p. 250

- ↑ Girdlestone, p. 400

- ↑ Tovey, p. 45

- ↑ Einstein, p. 311

- ↑ Stock, p. 212

- ↑ Steinberg, p. 313

- ↑ Einstein, p. 138

- ↑ Girdlestone, p. 404

- ↑ Tovey, p. 45

- ↑ Steinberg, p. 313

- ↑ Stock, p. 213

- ↑ Steinberg, p. 313

- ↑ Girdlestone, p. 404

- ↑ Tischler, p. 111

- ↑ Levin, p. 392

- ↑ Brendel, Alfred (27 June 1985). "A Mozart Player Gives Himself Advice". The New York Review of Books.

- ↑ Hutchings, p. 174

- ↑ Hutchings, p. 173

- ↑ Rosen, p. 250

- ↑ Girdlestone, p. 407

- ↑ Girdlestone, p. 408

- ↑ Girdlestone, p. 408

- ↑ Hutchings, p. 174

- ↑ Tovey, p. 46

- ↑ Girdlestone, p. 409

- ↑ Girdlestone, p. 408

- ↑ Girdlestone, p.410

- ↑ King, p. 99

- ↑ Girdlestone, p.410

- ↑ Tovey, p. 46

- ↑ Einstein, p. 311

- ↑ Tovey, p. 46

- ↑ Kinderman, p. 297

- ↑ Wen, pp. 123-124

- ↑ Wen, p. 107

- ↑ Girdlestone, p. 410

- ↑ Einstein, p. 138

- ↑ Keefe (2001), p. 78

- ↑ King, p. 95

- ↑ Hutchings, p. 174

Sources

- Blume, Friedrich (1956). "The Concertos: (1) Their Sources". In H. C. Robbins Landon and Donald Mitchell. The Mozart Companion. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 2048847.

- Bribitzer-Stull, Matthew (2006). "The Cadenza as Parenthesis: An Analytic Approach". Journal of Music Theory. 50 (2).

- Einstein, Alfred (1945). Mozart, His Character, His Work (1962 edition). New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 511324.

- Girdlestone, Cuthbert (1948). Mozart's Piano Concertos. London: Cassell. OCLC 247427085.

- Hutchings, A. (1948). A Companion to Mozart's Piano Concertos. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 20468493.

- Irving, John (2003). Mozart's Piano Concertos. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 0754607070.

- Keefe, Simon P. (2003). "The concertos in aesthetic and stylistic context". In Simon P. Keefe. The Cambridge Companion to Mozart. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521001927.

- Keefe, Simon P. (2001). Mozart's Piano Concertos: Dramatic Dialogue in the Age of Enlightenment. Rochester, New York: Boydell Press. ISBN 085115834X.

- Kerman, Joseph (1994). "Mozart's Piano Concertos and Their Audience". In James M. Morris. On Mozart. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521476615.

- Kinderman, William (1996). "Dramatic Development and Narrative Design in the First Movement of Mozart's Piano Concerto in C Minor, K. 491". In Neil Zaslaw. Mozart's Piano Concertos: Text, Context, Interpretation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472103148.

- King, A. Hyatt (1952). "Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)". In Ralph Hill. The Concerto. Melbourne: Penguin Books. OCLC 899058745.

- Lindeman, Stephan D. (1999). Structural Novelty and Tradition in the Early Romantic Piano Concerto. Stuyvesant, New York: Pendragon Press. ISBN 1576470008.

- Levin, Robert D. (2003). "Mozart's Keyboard Concertos". In Robert L. Marshall. Eighteenth-Century Keyboard Music. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415966426.

- Libin, Laurence (2003). "The Instruments". In Robert L. Marshall. Eighteenth-Century Keyboard Music. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415966426.

- Mishkin, Henry G. (1975). "Incomplete Notation in Mozart's Piano Concertos". The Musical Quarterly. 61 (3). doi:10.1093/mq/lxi.3.345.

- Rosen, Charles (1976). The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (Revised ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0571049052.

- Steinberg, Michael (1998). The Concerto : A Listener's Guide. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019802634X.

- Stock, Jonathan P.J. (May 1997). "Orchestration as Structural Determinant: Mozart's Deployment of Woodwind Timbre in the Slow Movement of the C Minor Piano Concerto K. 491". Music & Letters. 78 (3).

- Tischler, Hans (1966). A Structural Analysis of Mozart's Piano Concertos. Brooklyn: Institute of Mediaeval Music. ISBN 0912024801.

- Tovey, Donald (1936). Essays in Musical Analysis, volume 3. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 22689261.

- Wen, Eric (1990). "Enharmonic transformation in the first movement of Mozart's Piano Concerto in C Minor, K. 491". In Hedi Siegel. Schenker Studies: Symposium: Papers. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521360382.

External links

- Konzert für Klavier und Orchester in c KV 491: Score and critical report (German) in the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe

- Piano Concerto No. 24: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- BBC Discovering Music (browse for .ram file for this work)