Product (category theory)

In category theory, the product of two (or more) objects in a category is a notion designed to capture the essence behind constructions in other areas of mathematics such as the cartesian product of sets, the direct product of groups, the direct product of rings and the product of topological spaces. Essentially, the product of a family of objects is the "most general" object which admits a morphism to each of the given objects.

Definition

Let C be a category with some objects X1 and X2. A product of X1 and X2 is an object X (often denoted X1 × X2) together with a pair of morphisms π1 : X → X1, π2 : X → X2 that satisfy the following universal property:

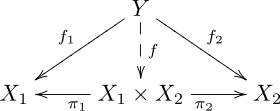

- for every object Y and pair of morphisms f1 : Y → X1, f2 : Y → X2 there exists a unique morphism f : Y → X such that the following diagram commutes:

The unique morphism f is called the product of morphisms f1 and f2 and is denoted < f1, f2 >. The morphisms π1 and π2 are called the canonical projections or projection morphisms.

Above we defined the binary product. Instead of two objects we can take an arbitrary family of objects indexed by some set I. Then we obtain the definition of a product.

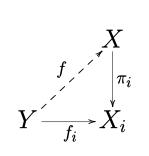

An object X is the product of a family (Xi)i∈I of objects iff there exist morphisms πi : X → Xi, such that for every object Y and a I-indexed family of morphisms fi : Y → Xi there exists a unique morphism f : Y → X such that the following diagrams commute for all i∈I:

The product is denoted Πi∈I Xi; if I = {1, ..., n}, then denoted X1 × ... × Xn and the product of morphisms is denoted < f1, ..., fn >.

Equational definition

Alternatively, the product may be defined through equations. So, for example, for the binary product:

- Existence of f is guaranteed by the operation < -,- >.

- Commutativity of the diagrams above is guaranteed by the equality ∀f1, ∀f2, ∀i∈{1, 2}, πi o < f1, f2 > = fi.

- Uniqueness of f is guaranteed by the equality ∀g : Y → X, < π1 o g, π2 o g > = g.[1]

As a limit

The product is a special case of a limit. This may be seen by using a discrete category (a family of objects without any morphisms, other than their identity morphisms) as the diagram required for the definition of the limit. The discrete objects will serve as the index of the components and projections. If we regard this diagram as a functor, it is a functor from the index set I considered as a discrete category. The definition of the product then coincides with the definition of the limit, { f }i being a cone and projections being the limit (limiting cone).

Universal property

Just as the limit is a special case of the universal construction, so is the product. Starting with the definition given for the universal property of limits, take J as the discrete category with two objects, so that CJ is simply the product category C × C. The diagonal functor Δ : C → C × C assigns to each object X the ordered pair (X, X) and to each morphism f the pair (f, f). The product X1 × X2 in C is given by a universal morphism from the functor Δ to the object (X1, X2) in C × C. This universal morphism consists of an object X of C and a morphism (X, X) → (X1, X2) which contains projections.

Examples

In the category of sets, the product (in the category theoretic sense) is the cartesian product. Given a family of sets Xi the product is defined as

- Πi∈I Xi := { (xi)i∈I | ∀i∈I, xi∈Xi }

with the canonical projections

- πj : Πi∈I Xi → Xj, πj((xi)i∈I) := xj.

Given any set Y with a family of functions

- fi : Y → Xi,

the universal arrow f is defined as

- f : Y → Πi∈I Xi, f(y) := (fi(y))i∈I .

Other examples:

- In the category of topological spaces, the product is the space whose underlying set is the cartesian product and which carries the product topology. The product topology is the coarsest topology for which all the projections are continuous.

- In the category of modules over some ring R, the product is the cartesian product with addition defined componentwise and distributive multiplication.

- In the category of groups, the product is the direct product of groups given by the cartesian product with multiplication defined componentwise.

- In the category of relations (Rel), the product is given by the disjoint union. (This may come as a bit of a surprise given that the category of sets (Set) is a subcategory of Rel.)

- In the category of algebraic varieties, the categorical product is given by the Segre embedding.

- In the category of semi-abelian monoids, the categorical product is given by the history monoid.

- A partially ordered set can be treated as a category, using the order relation as the morphisms. In this case the products and coproducts correspond to greatest lower bounds (meets) and least upper bounds (joins).

Discussion

The product does not necessarily exist. For example, an empty product (i.e. I is the empty set) is the same as a terminal object, and some categories, such as the category of infinite groups, do not have a terminal object: given any infinite group G there are infinitely many morphisms ℤ → G, so G cannot be terminal.

If I is a set such that all products for families indexed with I exist, then one can treat each product as a functor CI → C.[2] How this functor maps objects is obvious. Mapping of morphisms is subtle, because product of morphisms defined above does not fit. First, consider binary product functor, which is a bifunctor. For f1 : X1 → Y1, f2 : X2 → Y2 we should find a morphism X1 × X2 → Y1 × Y2. We choose < f1 o π1, f2 o π2 >. This operation on morphisms is called cartesian product of morphisms.[3] Second, consider product functor. For families {X}i, {Y}i, fi : Xi → Yi we should find a morphism Πi∈I Xi → Πi∈I Yi. We choose the product of morphisms {fi o πi }i.

A category where every finite set of objects has a product is sometimes called a cartesian category[3] (although some authors use this phrase to mean "a category with all finite limits").

The product is associative. Suppose C is a cartesian category, product functors have been chosen as above, and 1 denotes the terminal object of C. We then have natural isomorphisms

These properties are formally similar to those of a commutative monoid; a category with its finite products constitutes a symmetric monoidal category.

Distributivity

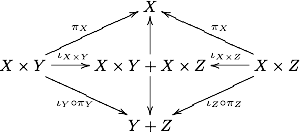

In a category with finite products and coproducts, there is a canonical morphism X×Y+X×Z → X×(Y+Z), where the plus sign here denotes the coproduct. To see this, note that we have various canonical projections and injections which fill out the diagram

The universal property for X×(Y+Z) then guarantees a unique morphism X×Y+X×Z → X×(Y+Z). A distributive category is one in which this morphism is actually an isomorphism. Thus in a distributive category, one has the canonical isomorphism

See also

- Coproduct – the dual of the product

- Diagonal functor – the left adjoint of the product functor.

- Limit and colimits

- Equalizer

- Inverse limit

- Cartesian closed category

- Categorical pullback

References

- ↑ Lambek J., Scott P. J. (1988). Introduction to Higher-Order Categorical Logic. Cambridge University Press. p. 304.

- ↑ Lane, S. Mac (1988). Categories for the working mathematician (1st ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 37. ISBN 0-387-90035-7.

- 1 2 Michael Barr, Charles Wells (1999). Category Theory - Lecture Notes for ESSLLI. p. 62.

- Adámek, Jiří; Horst Herrlich; George E. Strecker (1990). Abstract and Concrete Categories (PDF). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-60922-6.

- Barr, Michael; Charles Wells (1999). Category Theory for Computing Science (PDF). Les Publications CRM Montreal (publication PM023). Chapter 5.

- Mac Lane, Saunders (1998). Categories for the Working Mathematician. Graduate Texts in Mathematics 5 (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-387-98403-8.

- Definition 2.1.1 in Borceux, Francis (1994). Handbook of categorical algebra. Encyclopedia of mathematics and its applications 50-51, 53 [i.e. 52]. Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-521-44178-1.

External links

- Interactive Web page which generates examples of products in the category of finite sets. Written by Jocelyn Paine.

- Product in nLab