Quality-adjusted life year

The quality-adjusted life year or quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) is a generic measure of disease burden, including both the quality and the quantity of life lived.[1][2] It is used in economic evaluation to assess the value for money of medical interventions. One QALY equates to one year in perfect health. If an individual's health is below this maximum, QALYs are accrued at a rate of less than 1 per year. To be dead is associated with 0 QALYs, and in some circumstances it is possible to accrue negative QALYs to reflect health states deemed 'worse than dead'.

Use

The QALY is often used in cost-utility analysis in order to estimate the cost-per-QALY associated with a health care intervention. This incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) can then be used to allocate healthcare resources, often using a threshold approach.[3]

In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, which advises on the use of health technologies within the National Health Service, has since at least 2013 used "£ per QALY" to evaluate their utility.[4][5]

Meaning

The concept of the QALY is credited to work by Klarman[6] and later Fanshel and Bush[7] and Torrance [8] who suggested the idea of length of life adjusted by indices of functionality or health.[9] It was officially named the QALY in print in an article by Zeckhauser and Shepard[10] It was later promoted through medical technology assessment conducted by the US Congress Office of Technology Assessment.

Then, in 1980, Pliskin proposed a justification of the construction of the QALY indicator using the multiattribute utility theory: if a set of conditions pertaining to agent preferences on life years and quality of life are verified, then it is possible to express the agent’s preferences about couples (number of life years/health state), by an interval (Neumannian) utility function. This utility function would be equal to the product of an interval utility function on « life years », and an interval utility function on « health state ». According to Pliskin et al., The QALY model requires utility independent, risk neutral, and constant proportional tradeoff behaviour.[11] Because of these theoretical assumptions, the meaning and usefulness of the QALY is debated.[12][13][14] Perfect health is hard, if not impossible, to define. Some argue that there are health states worse than being dead, and that therefore there should be negative values possible on the health spectrum (indeed, some health economists have incorporated negative values into calculations). Determining the level of health depends on measures that some argue place disproportionate importance on physical pain or disability over mental health.[15]

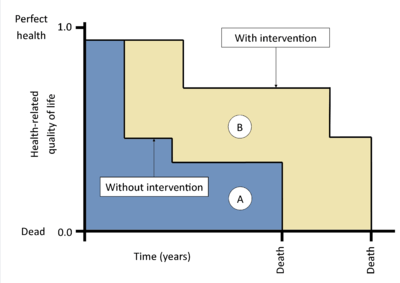

Calculation

The QALY is a measure of the value of health outcomes. Since health is a function of length of life and quality of life, the QALY was developed as an attempt to combine the value of these attributes into a single index number. The basic idea underlying the QALY is simple: it assumes that a year of life lived in perfect health is worth 1 QALY (1 Year of Life × 1 Utility value = 1 QALY) and that a year of life lived in a state of less than this perfect health is worth less than 1. In order to determine the exact QALY value, it is sufficient to multiply the utility value associated with a given state of health by the years lived in that state. QALYs are therefore expressed in terms of "years lived in perfect health": half a year lived in perfect health is equivalent to 0.5 QALYs (0.5 years × 1 Utility), the same as 1 year of life lived in a situation with utility 0.5 (e.g. bedridden) (1 year × 0.5 Utility). QALYs can then be incorporated with medical costs to arrive at a final common denominator of cost/QALY. This parameter can be used to develop a cost-effectiveness analysis of any treatment. Data is collected through use of surveys such as EQ-5D.

Weighting

The "weight" values between 0 and 1 are usually determined by methods such as those proposed in the Journal of Health Economics:[16]

- Time-trade-off (TTO): Respondents are asked to choose between remaining in a state of ill health for a period of time, or being restored to perfect health but having a shorter life expectancy.

- Standard gamble (SG): Respondents are asked to choose between remaining in a state of ill health for a period of time, or choosing a medical intervention which has a chance of either restoring them to perfect health, or killing them.

- Visual analogue scale (VAS): Respondents are asked to rate a state of ill health on a scale from 0 to 100, with 0 representing being dead and 100 representing perfect health. This method has the advantage of being the easiest to ask, but is the most subjective.

Another way of determining the weight associated with a particular health state is to use standard descriptive systems such as the EuroQol Group's EQ-5D questionnaire, which categorises health states according to five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities (e.g. work, study, homework or leisure activities), pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression.[17]

Debate

The method of ranking interventions on grounds of their cost per QALY gained ratio (or ICER) is controversial because it implies a quasi-utilitarian calculus to determine who will or will not receive treatment.[18] However, its supporters argue that since health care resources are inevitably limited, this method enables them to be allocated in the way that is approximately optimal for society, including most patients. Another concern is that it does not take into account equity issues such as the overall distribution of health states - particularly since younger, healthier cohorts have many times more QALYs than older or sicker individuals. As a result, QALY analysis may undervalue treatments which benefit the elderly or others with a lower life expectancy. Also, many would argue that all else being equal, patients with more severe illness should be prioritised over patients with less severe illness if both would get the same absolute increase in utility.[19] In 2013 the results of a European Commission Project, ECHOUTCOME[20] recommended to not use QALYs in health decision making after surveying 1361 subjects in the UK, Belgium, France and Italy and establishing that the four theoretical assumptions underlying QALYs are invalid (quality of life should be measured in consistent intervals; life years and QOL should be independent; people should be neutral about risk; and willingness to sacrifice life years should be constant over time), explaining why divergent QALY results can be generated using the same dataset.[21][22]

Future development

The UK Medical Research Council is exploring including other wellbeing factors (not just health) in future measures.[23]

See also

- Case mix index

- Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry

- Cost-utility analysis

- Disability-adjusted life year (DALY)

- Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (United Kingdom)

- Quality of life and measurements such as MANSA and Life Quality Index

References

- ↑ "Measuring effectiveness and cost effectiveness: the QALY". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Archived from the original on August 9, 2009.

- ↑ "Entry for "QALY"". Bandolier Journal Glossary. Oxford University.

- ↑ Weinstein, Milton; Zeckhauser, Richard (1973-04-01). "Critical ratios and efficient allocation". Journal of Public Economics. 2 (2): 147–157. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(73)90002-9.

- ↑ "Measuring effectiveness and cost effectiveness: the QALY". NICE. 20 April 2010. Retrieved 15 Jun 2015.

- ↑ "Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013". NICE. 2013. Retrieved 15 Jun 2015.

- ↑ Klarman, Herbert E.; Francis, John O'S; Rosenthal, Gerald D. (1968). "Cost effectiveness analysis applied to the treatment of chronic renal disease". Medical care. 6 (1): 48–54. doi:10.1097/00005650-196801000-00005. Retrieved 2014-05-06.

- ↑ Fanshel, Sol; Bush, J.W. (1970). "A health-status index and its application to health-services outcomes" (PDF). Operations Research. 18 (6): 1021–66. doi:10.1287/opre.18.6.1021. Retrieved 2014-05-06.

- ↑ Torrance, G W; Thomas, W.H.; Sackett, D.L. (1972). "A utility maximization model for evaluation of health care programs". Health services research. 7 (2): 118–133. ISSN 0017-9124. PMC 1067402

. PMID 5044699.

. PMID 5044699. - ↑ Kaplan, Robert M. (1995). "Utility assessment for estimating quality-adjusted life years" (PDF). Valuing health care: Costs, benefits, and effectiveness of pharmaceuticals and other medical technologies: 31–60. Retrieved 2014-05-06.

- ↑ Zeckhauser, Richard; Shepard, Donald (1976). "Where Now for Saving Lives?". Law and Contemporary Problems. 40 (4): 5–45. doi:10.2307/1191310. ISSN 0023-9186.

- ↑ Pliskin, J. S.; Shepard, D. S.; Weinstein, M. C. (1980). "Utility Functions for Life Years and Health Status". Operations Research. 28: 206–24. doi:10.1287/opre.28.1.206. JSTOR 172147.

- ↑ Prieto, Luis; Sacristán, José A (2003). "Problems and solutions in calculating quality-adjusted life years (QALYs)". Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 1: 80. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-80. PMC 317370

. PMID 14687421.

. PMID 14687421.

- ↑ Schlander, Michael (2007-07-09). Lost in Translation? Over-Reliance on QALYs May Lead to Neglect of Relevant Evidence (PDF). Copenhagen, Denmark: Institute for Innovation & Valuation in Health Care. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- ↑ Mortimer, D.; Segal, L. (2007). "Comparing the Incomparable? A Systematic Review of Competing Techniques for Converting Descriptive Measures of Health Status into QALY-Weights". Medical Decision Making. 28 (1): 66–89. doi:10.1177/0272989X07309642. PMID 18263562.

- ↑ Dolan, P (January 2008). "Developing methods that really do value the 'Q' in the QALY" (PDF). Health Economics, Policy and Law. 3 (1): 69–77. doi:10.1017/S1744133107004355.

- ↑ Torrance, George E. (1986). "Measurement of health state utilities for economic appraisal: A review". Journal of Health Economics. 5: 1–30. doi:10.1016/0167-6296(86)90020-2. Retrieved 2014-12-01.

- ↑ EuroQol Group (1990-12-01). "EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life". Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 16 (3): 199–208. doi:10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. ISSN 0168-8510. PMID 10109801.

- ↑ Schlander, Michael (2010-05-23), Measures of efficiency in healthcare: QALMs about QALYs? (PDF), Institute for Innovation & Valuation in Health Care, retrieved 2010-05-23

- ↑ Nord, Erik; Pinto, Jose Luis; Richardson, Jeff; Menzel, Paul; Ubel, Peter (1999). "Incorporating societal concerns for fairness in numerical valuations of health programmes". Health Economics. 8 (1): 25–39. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(199902)8:1<25::AID-HEC398>3.0.CO;2-H. PMID 10082141.

- ↑ "Echoutcome". echoutcome.eu.

- ↑ Dreaper, J. (24 January 2013). "Researchers claim NHS drug decisions are flawed". BBC News.

- ↑ Holmes D (March 2013). "Report triggers quibbles over QALYs, a staple of health metrics". Nat. Med. 19 (3): 248. doi:10.1038/nm0313-248. PMID 23467219.

- ↑ https://www.mrc.ac.uk/funding/how-we-fund-research/highlight-notices/improving-cross-sector-comparisons-beyond-qaly/