R.U.R.

| R.U.R. | |

|---|---|

|

A scene from the play, showing three robots | |

| Written by | Karel Čapek |

| Date premiered | 25 January 1921 |

| Original language | Czech |

| Genre | Science fiction |

R.U.R. is a 1920 science fiction play by the Czech writer Karel Čapek. R.U.R. stands for Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti (Rossum’s Universal Robots).[1] However, the English phrase Rossum’s Universal Robots had been used as the subtitle in the Czech original.[2] It premiered on 25 January 1921 and introduced the word "robot" to the English language and to science fiction as a whole.[3]

R.U.R. quickly became famous and was influential early in the history of its publication.[4][5][6] By 1923, it had been translated into thirty languages.[4][7]

The play begins in a factory that makes artificial people, called roboti (robots), from synthetic organic matter. They are not exactly robots by the current definition of the term; these creatures are closer to the modern idea of cyborgs, androids or even clones, as they may be mistaken for humans and can think for themselves. They seem happy to work for humans at first but a robot rebellion leads to the extinction of the human race. Čapek later took a different approach to the same theme in War with the Newts, in which non-humans become a servant class in human society.[8]

R.U.R. is dark but not without hope and was successful in its day in both Europe and North America.[9]

Characters

Parentheses indicate differences in translations.

- Humans[10]

- Harry Domin (Domain) — General Manager, R.U.R.

- Fabry — Chief Engineer, R.U.R.

- Dr. Gall — Head of the Physiological Department, R.U.R.

- Dr. Hellman (Hallemeier) — Psychologist-in-Chief

- Jacob Berman (Busman) — Managing Director, R.U.R.

- Alquist — Clerk of the Works, R.U.R.

- Helena Glory — President of the Humanity League, daughter of President Glory

- Emma (Nana) — Helena's maid

- Robots and robotesses

- Marius, a robot

- Sulla, a robotess

- Radius, a robot

- Primus, a robot

- Helena, a robotess

- Daemon (Damon), a robot

Plot

Act I

Helena, the daughter of the president of a major industrial power, arrives at the island factory of Rossum's Universal Robots. She meets Domin, the General Manager of R.U.R., who tells her the history of the company:

In 1920 a man named Rossum came to the island to study marine biology, and in 1932 he accidentally discovered a chemical that behaved exactly like protoplasm, except that it did not mind being knocked around. Rossum attempted to make a dog and a man, but failed. His nephew came to see him, and the two argued non-stop, largely because Old Rossum only wanted to create animals to prove that not only was God not necessary but that there was no God at all, and Young Rossum only wanted to make himself rich. Eventually, Young Rossum locked his uncle in a laboratory to play with his monsters and mutants, while Young Rossum built factories and cranked out Robots by the thousands. By the time the play takes place (in the 1950s or 1960s, presumably), Robots are cheap and available all over the world. They have become absolutely necessary because they allow products to be made at a fifth the previous cost.

Helena meets Fabry, Dr. Gall, Alquist, Busman, and Hallemeier, and reveals she is a representative of the League of Humanity, a human rights organization that wishes to "free" the Robots. The managers of the factory find this a ridiculous proposition, since they see Robots as appliances. Helena requests that the Robots be paid so that they can buy things they like, but the Robots do not like anything. Helena is eventually convinced that the League Of Humanity is a waste of money, but continues to argue on the fact that robots should still have a "soul". Later, Domin confesses that he loves Helena and forces her into an engagement.

Act II

Ten years later, Helena and her nurse Nana are talking about current events—particularly the decline in human births. Helena and Domin reminisce about the day they met and summarize the last ten years of world history, which has been shaped by the new worldwide Robot-based economy. Helena meets Dr. Gall's new Robot experiment, Radius, and Dr Gall describes his experimental Robotess, Robot Helena. Both are more advanced, fully featured versions. In secret, Helena burns the formula required to create Robots. The revolt of the Robots reaches Rossum's island as the act ends.

Act III

The characters sense that the very universality of the Robots presents a danger. Reminiscent of the Tower of Babel, the characters discuss whether creating national Robots who were unable to communicate beyond their language group would have been a good idea. As Robot forces lay siege to the factory, Helena reveals she has burned the formula necessary to make new robots. The characters lament the end of humanity and defend their actions, despite the fact that their imminent deaths are a direct result of those actions. Busman is killed attempting to negotiate a peace with the Robots, who then storm the factory and kill all the humans except for Alquist, whom the Robots spare because they recognize that "he works with his hands like the Robots."[11]

Epilogue

Years have passed and all humans had been killed by the robot revolution except for Alquist. He has been working to recreate the formula that Helena destroyed. Because he is not a scientist, he has not made any progress. He has begged the robot government to search for surviving humans, and they have done so. There are none. Officials from the robot government approach Alquist and first order and then beg him to complete the formula, even if it means he will have to kill and dissect other Robots to do so. Alquist yields, agreeing to kill and dissect, which completes the circle of violence begun in Act Two. Alquist is disgusted by it. Robots Primus and Helena develop human feelings and fall in love. Playing a hunch, Alquist threatens to dissect Primus and then Helena; each begs him to take him- or herself and spare the other. Alquist realizes that they are the new Adam and Eve, and gives charge of the world to them.

Robots

The Robots described in Čapek's play are not robots in the popularly understood sense of an automaton. They are not mechanical devices, but rather artificial biological organisms that may be mistaken for humans. A comic scene at the beginning of the play shows Helena arguing with her future husband, Harry Domin, because she cannot believe his secretary is a robotess:

DOMIN: Sulla, let Miss Glory have a look at you.

HELENA: (stands and offers her hand) Pleased to meet you. It must be very hard for you out here, cut off from the rest of the world.

SULLA: I do not know the rest of the world Miss Glory. Please sit down.

HELENA: (sits) Where are you from?

SULLA: From here, the factory

HELENA: Oh, you were born here.

SULLA: Yes I was made here.

HELENA: (startled) What?

DOMIN: (laughing) Sulla isn't a person, Miss Glory, she's a robot.

HELENA: Oh, please forgive me ...

In a limited sense, they resemble more modern conceptions of man-made life forms, such as the Replicants in Blade Runner, and the humanoid Cylons in the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica, but in Čapek's time there was no conception of modern genetic engineering (DNA's role in heredity was not confirmed until 1952). There are descriptions of kneading-troughs for robot skin, great vats for liver and brains, and a factory for producing bones. Nerve fibers, arteries, and intestines are spun on factory bobbins, while the Robots themselves are assembled like automobiles.[12] Čapek's robots are living biological beings, but they are still assembled, as opposed to grown or born.

One critic has described Čapek's Robots as epitomizing "the traumatic transformation of modern society by the First World War and the Fordist assembly line."[12]

Origin of the word

The play introduced the word robot, which displaced older words such as "automaton" or "android" in languages around the world. In an article in Lidové noviny Karel Čapek named his brother Josef as the true inventor of the word.[13] In Czech, robota means forced labour of the kind that serfs had to perform on their masters' lands and is derived from rab, meaning "slave".[14]

The name Rossum is an allusion to the Czech word rozum, meaning "reason", "wisdom", "intellect" or "common-sense". [8] It has been suggested that the allusion might be preserved by translating "Rossum" as "Reason" but only the Majer/Porter version translates the word as "Reason".[15]

Production history

The work was published in Prague by Aventinum in 1920 and premiered in that city on 25 January 1921. It was translated from Czech into English by Paul Selver and adapted for the English stage by Nigel Playfair in 1923. Selver's translation abridged the play and eliminated a character, a robot named "Damon".[16] In April 1923 Basil Dean produced R.U.R. for the Reandean Company at St Martin's Theatre, London.[17]

The American première was at the Garrick Theatre in New York City in October 1922, where it ran for 184 performances, a production in which Spencer Tracy and Pat O'Brien played robots in their Broadway debuts.[18]

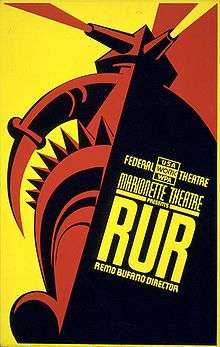

It also played in Chicago and Los Angeles during 1923.[19] In the late 1930s, the play was staged in the U.S. by the Federal Theatre Project's Marionette Theatre in New York.

In 1989, a new, unabridged translation by Claudia Novack-Jones restored the elements of the play eliminated by Selver.[16][20] Another unabridged translation was produced by Peter Majer and Cathy Porter for Methuen Drama in 1999. [15]

Critical reception

Reviewing the New York production of R.U.R., The Forum magazine described the play as "thought-provoking" and "a highly original thriller".[21] John Clute has lauded R.U.R. as "a play of exorbitant wit and almost demonic energy" and lists the play as one of the "classic titles" of inter-war science fiction.[22] Luciano Floridi has described the play thus: "Philosophically rich and controversial, R.U.R. was unanimously acknowledged as a masterpiece from its first appearance, and has become a classic of technologically dystopian literature."[23] Jarka M. Burien called R.U.R. a "theatrically effective, prototypal sci-fi melodrama".[9] On the other hand, Isaac Asimov, author of the Robot series of books and creator of the Three Laws of Robotics, stated: "Capek's play is, in my own opinion, a terribly bad one, but it is immortal for that one word. It contributed the word 'robot' not only to English but, through English, to all the languages in which science fiction is now written."[3] In fact, Asimov's "Laws of Robotics" are specifically and explicitly designed to prevent the kind of situation depicted in R.U.R. - since Asimov's Robots are created with a built-in total inhibition against harming human beings or disobeying them.

Adaptations

On 11 February 1938, a thirty-five-minute adaptation of a section of the play was broadcast on BBC Television – the first piece of television science-fiction ever to be broadcast.[24] In 1941 BBC radio presented a radio play version, and in 1948, another television adaptation – this time of the entire play, running to ninety minutes – was screened by the BBC. In this version Radius was played by Patrick Troughton who was later the second actor to play The Doctor in Doctor Who, None of these three productions survive in the BBC's archives. BBC Radio 3 dramatised the play again in 1989, and this version has been released commercially. The Hollywood Theater of the Ear dramatized an unabridged audio version of R.U.R. which is available on the collection 2000x: Tales of the Next Millennia.[25][26]

In August 2010, Portuguese multi-media artist Leonel Moura's R.U.R.: The Birth of the Robot, inspired by the Capek play, was performed at Itaú Cultural in São Paulo, Brazil. It utilized actual robots on stage interacting with the human actors.[27]

An electro-rock musical, Save The Robots is based on R.U.R., featuring the music of the New York City pop-punk art-rock band Hagatha.[28] This version with book and adaptation by E. Ether, music by Rob Susman, and lyrics by Clark Render was an official selection of the 2014 New York Musical Theatre Festival season.[29]

On 26 November 2015 The RUR-Play: Prologue, the world's first version of R.U.R. with robots appearing in all the roles, was presented during the robot performance festival of Cafe Neu Romance at the gallery of the National Library of Technology in Prague, Czech Republic.[30][31][32][33] The concept and initiative for the play came from Christian Gjørret, the leader of "Vive Les Robots!",[34] who on 29 January 2012, during a meeting with Steven Canvin of LEGO Group, presented the proposal for Lego to support the play with their LEGO MINDSTORMS robot kit. On 29 April 2015 the Czech R.U.R. team,[35] which consisted primarily of high school students from Gymnazium Jesenik[36] began to develop the play. Paul Selver and Nigel Playfair's 1923 translation was used and the members of the team provided the voices. The play was directed by Filip Worm and the full realization was led by Roman Chasák.[30]

In popular culture

- In the American science fiction television series Dollhouse, the antagonist corporation, Rossum Corp., is named after the play.[37]

- In the Star Trek episode "Requiem for Methuselah", the android's name is Rayna Kapec (an anagram, though not a homophone, of Capek, Čapek without its háček).

- In Batman: The Animated Series, the scientist that created the HARDAC machine is named Karl Rossum. HARDAC created mechanical replicants to replace existing humans, with the ultimate goal of replacing all humans. One of the robots is seen driving a car with "RUR" as the license plate number.

- In the 1977 Doctor Who serial "The Robots of Death", the robot servants turn on their human masters under the influence of an individual named Taren Capel.

- In the 1995 science fiction series The Outer Limits, in the remake of the "I, Robot" episode from the original 1964 series, the business where the robot Adam Link is built is named "Rossum Hall Robotics".

- The 1999 Blake's 7 radio play The Syndeton Experiment included a character named Dr. Rossum who turned humans into robots.[38]

- In the "Fear of a Bot Planet" episode of the animated science fiction TV series Futurama, the Planet Express crew is ordered to make a delivery on a planet called "Chapek 9", which is inhabited solely by robots.

- In Howard Chaykin's Time² graphic novels, Rossum's Universal Robots is a powerful corporation and maker of robots.

See also

References

- ↑ Roberts, Adam (2006). The History of Science Fiction. New York, NY: PALGRAVE MACMILLAN. p. 168. ISBN 9780333970225.

- ↑ Kussi, Peter. Toward the Radical Center: A Čapek Reader. (33).

- 1 2 Asimov, Isaac (September 1979). "The Vocabulary of Science Fiction.". Asimov's Science Fiction.

- 1 2 Voyen Koreis. "Capek's RUR". Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Tim Madigan (July–August 2012). "RUR or RU Ain't A Person?". Philosophy Now. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ↑ Charles T. Rubin (2011). "Machine Morality and Human Responsibility". The New Atlantis. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ↑ "Ottoman Turkish Translation of R.U.R. – Library Details" (in Turkish). Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- 1 2 Roberts, Adam "Introduction", to RUR & War with the Newts. London, Gollancz, 2011, ISBN 0575099453 (pp. vi–ix).

- 1 2 Jarka M. Burien, "Čapek, Karel" in Gabrielle H. Cody, Evert Sprinchorn (eds.) The Columbia Encyclopedia of Modern Drama, Volume One. Columbia University Press, 2007. ISBN 0231144229, (pp. 224–225).

- ↑ On the meaning of the names, see Ivan Klíma, Karel Čapek: Life and Work, 2002, p. 82.

- ↑ Capek, Karel (2001). R.U.R.. translated by Paul Selver and Nigel Playfair. Dover Publications. p. 49.

- 1 2 John Rieder, "Karl Čapek", in Mark Bould, ed. Fifty Key Figures in Science Fiction. London, Routledge, 2010. ISBN 9780415439503 (pp.47-51)

- ↑ "Who did actually invent the word "robot" and what does it mean?". Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ "robot – definition of robot by the Free Online Dictionary". Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- 1 2 Klíma, Ivan, Karel Čapek:Life and Work. Catbird Press, 2002 ISBN 0945774532, (p. 260).

- 1 2 Abrash, Merritt (1991). "R.U.R. Restored and Reconsidered". 32 (2). Extrapolation: 185–192.

- ↑ History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe, Volume 3

- ↑ Corbin, John (10 October 1922). "A Czecho-Slovak Frankenstein". New York Times. p. 16/1.; R.U.R (1922) at the Internet Broadway Database

"Spencer Tracy Biography". Biography.com. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

Swindell, Larry. Spencer Tracy: A Biography. New American Library. pp. 40–42. - ↑ Butler, Sheppard (16 April 1923). "R.U.R.: A Satiric Nightmare". Chicago Daily Tribune. p. 21.; "Rehearsals in Progress for 'R.U.R.' Opening". Los Angeles Times. 24 November 1923. p. I13.

- ↑ Peter Kussi, ed. (1990). Toward the Radical Center: A Karel Čapek Reader. Highland Park, NJ: Catbird Press. pp. 34–109. ISBN 0945774060.

- ↑ Roland Holt, "Plays Tender and Tough", The Forum magazine, November 1922, (pp. 970-976).

- ↑ Clute, John (1995). Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 119, 214. ISBN 0751302023.

- ↑ Luciano Floridi, Philosophy and Computing: An Introduction. Taylor & Francis, 2002 ISBN 0203015312, (p.207).

- ↑ Telotte, J. P. (2008). The essential science fiction television reader. University Press of Kentucky. p. 210. ISBN 0-8131-2492-1.

- ↑ "2000x: Tales of the Next Millennia". Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ "2000X: Tales of the Next Millennia". Amazon.com. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ "Itaú Cultural: Emoção Art.ficial "2010 Schedule"". Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ "Save The Robots the Musical Summary".

- ↑ "Save The Robots: NYMF Developmental Reading Series 2014". Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- 1 2 "The RUR-Play:Prologue"

- ↑ "Cafe Neu Romance"

- ↑ "VIDEO: Poprvé bez lidí. Roboti zcela ovládli Čapkovu hru R.U.R.". iDNES.cz. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- ↑ "Entertainment Czech Republic Robots | AP Archive". www.aparchive.com. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- ↑ "Christian Gjorret on Roboto Performance Festival

- ↑ "R.U.R. Team"

- ↑ "Gynmazium Jesenik"

- ↑ Dollhouse:"Getting Closer" between 41:52 and 42:45

- ↑ Review of Syndeton Experiment, by Chris Orton at Judith Proctor's Blake's 7 site

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to R.U.R.. |

| Czech Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- R.U.R. in Czech from Project Gutenberg

- English language translation by David Wyllie

- Audio extracts from the SCI-FI-LONDON adaptation

- Karel Čapek bio.

- Online facsimile version of the 1920 first edition in Czech.