Race record

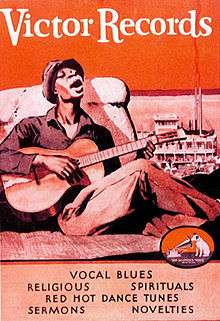

Race records were 78-rpm phonograph records marketed to African Americans from the 1920s through the early 1940s.[1] They primarily contained race music, comprising various African-American musical genres, including blues, jazz, and gospel music, and also comedy. These records were, at the time, the majority of commercial recordings of African-American artists in the US. Few African-American artists were marketed to white audiences. Race records were marketed by Okeh Records,[2] Emerson Records,[3] Vocalion Records,[4] Victor Talking Machine Company,[5] Paramount Records, and several other companies.

Terminology

Such records were labeled "race records" in reference to their marketing to African Americans, but white Americans gradually began to purchase such records as well. In the 16 October 1920 issue of the Chicago Defender, an African-American newspaper, an advertisement for Okeh records identified Mamie Smith as "Our Race Artist".[6] Most of the major recording companies issued "race" series of records from the mid-1920s to the 1940s.[7]

In hindsight the term race record may seem derogatory , but in the early 20th century the African-American press routinely used the term the Race to refer to African Americans as a whole and race man or race woman to refer to an African-American individual who showed pride in and support for African-American people and culture[8] (compare the cognate term la raza for Latin American cultural identity).

Transition to rhythm and blues

Billboard published a Race Records chart between 1945 and 1949, initially covering juke box plays and from 1948 also covering sales.[9] This was a revised version of the Harlem Hit Parade chart, which it had introduced in 1942.

In June 1949, at the suggestion of Billboard journalist Jerry Wexler, the magazine changed the name of the chart to Rhythm & Blues Records. Wexler wrote, "'Race' was a common term then, a self-referral used by blacks...On the other hand, 'Race Records' didn't sit well...I came up with a handle I thought suited the music well – 'rhythm and blues.'... [It was] a label more appropriate to more enlightened times."[10] The chart has since undergone further name changes, becoming the Soul chart in August 1969, the Black chart in June 1982,[11] the R&B chart in October 1990, and the R&B/Hip-Hop chart in December 1999.

See also

- Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs, for a history of the Billboard R&B record chart, known as the Race Records chart from February 1945 to June 1949

- African American music

- List of number-one rhythm and blues hits (United States) (Billboard, 1942–1959)

- Cover versions

References

- ↑ Oliver, Paul. "Race record." Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 13 Feb. 2015.

- ↑ photo

- ↑ photo

- ↑ photo

- ↑ photo

- ↑ Killmeier, Matthew A. (2002). "Race Music". St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture.

- ↑ Gammond, Peter (1991). The Oxford Companion to Popular Music. p. 477.

- ↑ Race Music: Chapter One

- ↑ Killmeier, Matthew A. (2002). "'race music' and 'race records' were terms used to categorize practically all types of African-American music in the 1940s". St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture.

- ↑ Wexler, Jerry; Ritz, David (1993). Rhythm and the Blues: A Life in American Music. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-224-03963-6.

- ↑ George, Nelson (June 26, 1982). "Black Music Charts: What's in a Name?". Billboard. p. 10.

- Ramsey, Guthrie P., Jr. (2003). Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop. Music of the African Diaspora, 7. Berkeley and London: University of California Press; Chicago, Illinois: Center for Black Music Research, Columbia College. ISBN 0-520-21048-4.

- Foreman, Ronald C., Jr. (1969). Jazz and Race Records, 1920–32. University Microfilms International.

Listening

External links

- St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture, Race music

- PBS, Race records

- NPR, Black and White: Crossing the Border, Closing the Gap