Red Ball Express

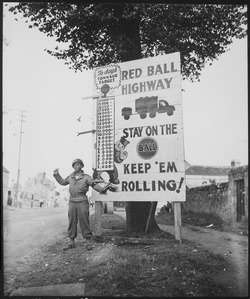

The Red Ball Express was a famed truck convoy system that supplied Allied forces moving quickly through Europe after breaking out from the D-Day beaches in Normandy in 1944. In order to expedite cargo to the front, trucks emblazoned with red balls followed a similarly marked route that had been closed to civilian traffic. These trucks were also given priority on regular roads.

The system originated in an urgent 36-hour meeting and began operating on August 25, 1944, staffed primarily with African-American soldiers.[1] At its peak, the Express operated 5,958 vehicles, and carried about 12,500 tons of supplies a day.[1] It ran until November 16, when the port facilities at Antwerp, Belgium, were opened, some French rail lines were repaired, and portable gasoline pipelines deployed.

History

Use of the term "Red Ball" to describe express cargo service dated at least to the end of the 19th century. Around 1892, the Santa Fe railroad began using it to refer to express shipping for priority freight and perishables.[2] Such trains and the tracks cleared for their use were marked with red balls. The term grew in popularity and was extensively used by the 1920s.

The need for such a priority transport service during World War II arose in the European Theater following the successful Allied invasion at Normandy in June 1944. In order to hobble the German army's ability to move forces and bring up reinforcements in a counter-attack the Allies had preemptively bombed the French railway system into ruins in the weeks leading up to the D-Day landing.

After the Allied breakout and the race to the Seine River, some 28 Allied divisions needed constant resupply. During offensive operations, each division consumed about 750 tons of supplies per day, totaling about 21,000 tons in all. The only way to deliver them was by truck – shortly giving birth to the Red Ball Express.

At its peak, it operated 5,958 vehicles and carried about 12,500 tons of supplies per day.[1][3] Colonel Loren Albert Ayers, known to his men as "Little Patton," was in charge of gathering two drivers for every truck, obtaining special equipment, and training port battalion personnel as drivers for long hauls. Able-bodied soldiers attached to other units whose duties were not critical were made drivers.[1] Almost 75% of Red Ball drivers were African Americans.[4]

In order to keep the supplies flowing without delay, two routes were opened from Cherbourg to the forward logistics base at Chartres. The northern route was used for delivering supplies, the southern for returning trucks. Both roads were closed to civilian traffic.[5]

"The highways in France are usually good, but are ordinarily not excessively wide. The needs of the rapidly advancing armies, consequently, promptly put the greatest possible demands upon them. To ease this strain, main highways leading to the front were set aside very early in the advance as "one way" roads from which all civil and local military traffic were barred. Tens of thousands of truckloads of supplies were pushed forward over these one way roads in a constant stream of traffic. Reaching the supply dumps in the forward areas, the trucks unloaded and returned empty to Arromanches, Cherbourg and the lesser landing places by way of other one way highways. Even the French railroads were, to some degree, operated similarly, with loaded trains moving forward almost nose to tail."[6]— For Want of a Nail: The Influence of Logistics on War (1948) by Hawthorne Daniel

Only convoys of at least five trucks were allowed,[1] to be escorted in front and behind by a jeep. In reality, it was not uncommon for individual trucks to depart Cherbourg as soon as they were loaded. It was also common to disable the engine governors to travel faster than 56 miles per hour (90 km/h).[1]

The convoys were a primary target of the German Luftwaffe. By 1944, however, German air power was so reduced that even these tempting and typically easy targets were rarely attacked. The biggest problems facing the Express were maintenance, finding enough drivers, and lack of sleep for overworked truckers.

In popular culture

Some trucking companies adopted the "red ball" name; In 1940, Gen. George Patton hired the Texas "Red Ball Express" trucking company to supply the Louisiana Maneuvers.

The World War II convoy was the subject of a movie named Red Ball Express in 1952. CBS later created a television sitcom called Roll Out which was loosely based on the movie.

See also

References

- Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Red Ball Express, 1944". U.S. Army Transportation Museum. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ↑ "Handling Fast Freight on the Santa Fe". The Railroad Gazette. The Railroad Gazette. 39 (8): 184–. August 25, 1905. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ The Real History of World War II: A New Look at the Past by Alan Axelrod, Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2008, ISBN 1-4027-4090-5, ISBN 978-1-4027-4090-9

- ↑ Rudi Williams (February 15, 2002). "African Americans Gain Fame as World War II Red Ball Express Drivers". United States Department of Defense. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ↑ Roland G. Ruppenthal (1995). The European Theater of Operations: Logistical Support of the Armies Vol 1. Washington,D.C.: US Army Center of Military History. p. 560.

- ↑ Daniel, Hawthorne. 1948. For Want of a Nail: The Influence of Logistics on War. New York: Whittlesey House. Pages 270-271.

- Bibliography

- David P. Colley (2000). The Road to Victory: The Untold Story of World War II's Red Ball Express. Potomac Books. ISBN 1-57488-173-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Red Ball Express. |