Richard Oswald (merchant)

Richard Oswald (1705 - 6 November 1784) was a Scottish merchant, slave trader, and advisor to the British government on trade regulations and the conduct of the American War of Independence. He is best known as the British peace commissioner who in 1782 negotiated the Peace of Paris.

Merchant

Oswald was born in Scotland in 1705 to the Reverend George Oswald of Dunnet. As a young man he lived for six years in Virginia as a merchant. He then returned to England and established himself in mercantile business in London for the next thirty years. While in London, he devoted a considerable amount of time to the African slave trade. In 1748, the firm of Alexander Grant, Richard Oswald, and Company purchased Bance Island, on the Sierra Leone River, where the Royal African Company had erected a fort. Oswald and his associates gained control of other small islands through treaties with native chiefs and established on Bance Island a trading station for factors in the trafficking of slaves.[1]

Oswald also was instrumental in directing English businessmen to promising locales in America for growing rice and indigo. Oswald directed English planter Francis Levett, who formerly worked for the Levant Company, to promising locations in British East Florida for his rice and indigo plantations, and urged East Florida Governor James Grant to make generous land grants to Levett, whom Oswald called his "worthy friend" to whom he owed "particular obligations."[2] Oswald's extensive network of business connections served him well in building his slave-tradingempire.[3]

Oswald was a premier "networker" of his day. He put together deals with investors who had immaculate connections, thus assuring himself of immediate social entree. In his petitions to the Board of Trade and Plantations for the settlement of Nova Scotia plantations, for instance, Oswald demonstrated his ability to bring together fellow profit-seekers who could pass muster with the King. Those he put forward for Nova Scotia, for instance, included: a former governor (Thomas Pownall); the Royal cartographer (JohnMitchell); Member of Parliament Robert Jackson; MP and Paymaster for the Marines John Tucker; and a Judge of the Marshalsea Court and cousin of adventurer Sir Michael Herries Levett Blackborne, who was himself stepbrother to Thomas Blackborne Thoroton, brother-in-law of the Marquess of Granby. This formula of connecting power-brokers was Oswald's stock-in-trade, and the key to his success.[4][5]

Oswald also had a cadre of young merchants whom he trained. Among these was John Levett, brother of planter Francis, who was in Oswald's employ as a young man. Levett (1725-1807) was born in Turkey to an English merchant father, and later settled in India, where he became a free merchant and invested in shipping, as well as becoming the Mayor of Calcutta. As a former trader in the Levant, Levett was ready to help Indian silk merchants supplant the former Mediterranean silk trade, which had fallen off. The English merchants were sensitive to the vagaries of fashion. Each year merchant Richard Oswald sent wigs to Levett in Calcutta, for instance. At the same time, Oswald associates like John Levett in Calcutta kept an eye on local trends, and adjusted their schemes to fit them. Levett, for instance, who had previously managed some German bread interests for Oswald, now planted cornfields in Bengal.

Oswald always kept his finger on the pulse of the world markets. When he needed Chinese laborers for his own estates, for instance, he approached John Levett in Calcutta, who employed Chinese laborers in his Bengal operations growing arrack for his distilleries. The relationships between the various associates in Oswald's extended trading empire grew so cozy that John Levett was corresponding with Oswald about the marble chimney-piece sculptures that his brother Francis Levett was purchasing on Oswald's behalf in Livorno, Italy, where Francis was then living as an English merchant.[6] Oswald was particularly close to the Levett and Thoroton families, as well as to the Duke of Rutland.[7] In letters to British General and East Florida Governor James Grant, Oswald confided that at one dinner of investors in East Florida and Nova Scotia that "Oswald had been dining at the Duke's with Lord Granby, Mr. Thoroton, and others where jokes passed round the table about the many settlements that would be needed to satisfy Mr. Thoroton's nine children."[8]

Recently published research identifies Richard Oswald as the likely anonymous author of the encyclopedic two volume American Husbandry (London, 1775).

Peace Commissioner

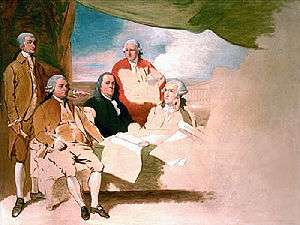

In 1782, Oswald was selected by Lord Shelburne to open informal negotiations with the Americans, to be held in Paris. Because of his prior experience living in America and his knowledge of its geography and trade, he had been consulted frequently by the British Ministry about matters concerning the war. Lord Shelburne chose Oswald because he thought his selection would appeal to Benjamin Franklin. Oswald shared Franklin's free trade commercial views; he possessed a "philosophic disposition"; and he had previously had a limited correspondence with Franklin.[9] Franklin was impressed with Oswald's negotiating skills and described him as a man with an "Air of great Simplicity and Honesty."[10]

Treaty of Paris

.jpg)

On July 25, 1782, official negotiations began. The preliminary articles were signed by Oswald for Great Britain, and John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and Henry Laurens for the United States on November 30, 1782. With almost no alterations, these articles were made into a treaty on September 3, 1783. Oswald was criticised in Britain for giving the Americans too much. The Duke of Richmond urged the recall of Oswald, charging that he "plead only the Cause of America, not of Britain."[11] Oswald resigned his cabinet post and returned to his estate of Auchincruive in Ayrshire where he died on November 6, 1784.

Oswald was related to American soldier and journalist Eleazer Oswald.[12]

After his death, fellow slave traders John and Alexander Anderson, also with interests on Bance Island, were appointed executors of his estate.[13]:612

References

- ↑ Stitt Robinson Jr., The Folly of Invading Virginia, 1781 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1953), 36.

- ↑ Julianton Plantation, English Plantations in East Florida, Florida History Online

- ↑ Citizens of the World: London Merchants and the Integration of the British Atlantic Community 1735-1785, David Hancock, Cambridge University Press, 1995

- ↑ Citizens of the World: London Merchants and the Integration of the British Atlantic Community, 1735-1785, David Hancock, Cambridge University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-521-62942-X, 9780521629423

- ↑ Representations to the Lords of Trade to the King, June 5, 1764, heritage.nf.ca

- ↑ Citizens of the World: London Merchants and the Integration of the British Atlantic Community, 1735-1785, David Hancock, Cambridge University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-521-62942-X, 9780521629423

- ↑ Colonial Plantations and Economy in Florida, Jane G. Landers, University Press of Florida, 2000

- ↑ The humor was explained by the relationships between the various families. "The central figure in the Granby- Rutland family group," according to the Florida Historical Quarterly, "was Thomas Thoroton who had married an illegitimate daughter of the Duke of Rutland and served him as his principal agent. Although Thoroton received no order in council for land in East Florida, he was a member of the East Florida Society and also of the Nova Scotia Society of London as well. Thoroton was the link between the East Florida and Nova Scotia speculators, particularly after Richard Oswald and James Grant decided to give up their Nova Scotia interests and concentrate on Florida.

- ↑ Robinson, Folly of Invading Virginia, 39.

- ↑ Robinson, Folly of Invading Virginia, 40.

- ↑ Robinson, Folly of Invading Virginia, 42.

- ↑ Boatner, Mark M. III (1994). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1., 820

- ↑ Laurens, Henry; Chesnutt, David R. (2003). The Papers of Henry Laurens: September 1, 1782-December 17, 1792. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press.