Rimfire ammunition

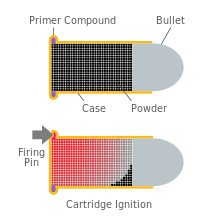

Rimfire is a method of ignition for metallic firearm cartridges as well as the cartridges themselves. It is called rimfire because the firing pin of a gun strikes and crushes the base's rim to ignite the primer. This is in contrast to the more common centerfire method, where the firing pin strikes the primer cap at the center of the base of the cartridge. The rim of the rimfire cartridge is essentially an extended and widened percussion cap which contains the priming compound, while the cartridge case itself contains the propellant powder and the projectile (bullet). Once the rim of the cartridge has been struck and the bullet discharged, the cartridge cannot be reloaded, because the head has been deformed by the firing pin impact. While many other different cartridge priming methods have been tried since the 19th century, only rimfire technology and centerfire technology survive today in significant use.

Characteristics

Rimfire cartridges are limited to low pressures because they require a thin case so that the firing pin can crush the rim and ignite the primer. Rimfire cartridges of .44 caliber (actually .45 caliber) up to .56 caliber were once common when black powder was used as a propellant. However, modern rimfire cartridges use smokeless powder which generates much higher pressures and tend to be of .22 caliber (5.5 mm) or smaller.[1] The low pressures necessitated by the rimfire design mean that rimfire firearms can be very light and inexpensive, which has helped lead to the continuing popularity of these small-caliber cartridges.

Economics

Rimfire cartridges are typically inexpensive, primarily due to the inherent cost-efficiency of the ability to manufacture the cartridges in large lots. The price of metals used in the cartridges (lead, copper and zinc) increased in 2002; the prices of the ammunition then further increased in 2012 possibly due to hoarding.[2]

History

The idea of placing a priming compound in the rim of the cartridge evolved from an 1831 patent, which called for a thin case, coated all along the inside with priming compound.

By 1845, this had evolved into the Flobert .22 BB Cap, in which the priming compound is distributed just inside the rim. The .22 BB Cap is essentially just a percussion cap with a round ball pressed in the front, and a rim to hold it securely in the chamber. Intended for use in an indoor "gallery" target rifle, it used no gunpowder, but relied entirely on the priming compound for propulsion. Its velocities were very low, comparable to an airgun. The next rimfire cartridge was the .22 Short, developed for Smith & Wesson's first revolver, in 1857; it used a longer rimfire case and 4 grains (260 mg) of black powder to fire a conical bullet.

This led to the .22 Long, with the same bullet weight as the short, but with a longer case and 5 grains (320 mg) of black powder. This was followed by the .22 Extra Long with a case longer than the .22 Long and a heavier bullet. The .22 Long Rifle is a .22 Long case loaded with the heavier Extra Long bullet intended for better performance in the long barrel of a rifle. Larger rimfire calibers were used during the American Civil War in the Henry Repeater, the Spencer Repeater, the Ballard rifle and the Frank Wesson carbine. While larger rimfire calibers were made, such as the, .30 rimfire, .32 rimfire, .38 rimfire .41 Short, the .44 Henry Flat devised for the famous Winchester 1866 carbine, up to the .58 Miller, the larger calibers were quickly replaced by centerfire versions, and today the .22 caliber rimfires are all that survive of these early rimfire cartridges.

The early 21st century has seen a revival in interest in rimfire cartridges, with two new rimfires introduced, both in .17 caliber (4.5 mm)[3] and the re-introduction of the 5mm Remington Rimfire Magnum in 2008.[4]

A new and increasingly popular rimfire, the 17 HMR is based on a .22 WMR casing with a smaller formed neck which accepts a .17 bullet. The advantages of the 17 HMR over .22 WMR and other rimfire cartridges are its much flatter trajectory, and its highly frangible hollow point bullets (often manufactured with plastic "ballistic tips" that improve the bullet's external ballistics). The .17 HM2 [Hornardy Mach 2] is based on the .22 Long Rifle and offers similar performance advantages over its parent cartridge, at a significantly higher cost. While .17 HM2 sells for about four times the cost of .22 Long Rifle ammunition (per box of 50 rounds), it is still significantly cheaper than most centerfire ammunition, and somewhat cheaper than the .17 HMR.

A notable rimfire cartridge that is still in production in Europe, and is chambered by the Winchester Model 39 in the 1920s, is the 9 mm Flobert. This cartridge can fire a small ball, but is primarily loaded with a small amount of shot, and used in smoothbore guns as a miniature shotgun, or "garden gun". Its power and range are very limited, making it suitable only for pest control.[3] An example of rare but modern 9 mm Flobert Rimfire among hunters in Europe is the 1.75" Brass Shotshell manufactured by Fiocchi in Lecco, Italy using a .25 oz shot of #8 shot with a velocity of 600 fps.

Below is a list of the most common current production rimfire ammunition:

- The powderless .22 Cap rounds (.22 CB), including BB Cap (.22 BB).

- .22 Short, used for target shooting and Olympic and ISSF 25 m Rapid Fire Pistol competition until 2005

- .22 Long (obsolete but available)

- .22 Long Rifle (.22 LR), the most common cartridge made

- .22 Stinger (a form of .22 Long Rifle with a slightly longer case and the same overall loaded length), its case is the basis for the .17 HM2[5]

- .22 Winchester Rimfire (.22 WRF) AKA .22 Remington Special (obsolete but available)

- .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire (.22 WMR)

- 5 mm Remington Rimfire Magnum (formerly discontinued but currently in commercial production by Aguila Ammunition/Centurion)

- .17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire (.17 HMR), a .17 caliber cartridge based on a modified .22 WMR case

- .17 Hornady Mach 2 (.17 HM2), a .17 caliber cartridge based on a modified .22 Stinger case[6]

- .17 Winchester Super Magnum (.17 WSM) a .17 caliber cartridge based on a modified .27 caliber nail gun blank case

Shot

Some rimfire cartridges are loaded with a small amount of #11 or #12 shot (about 1/15th ounce). This "rat-shot" is only marginally effective in close ranges, and is usually used for shooting rats or other small animals. It is also useful for shooting birds inside storage buildings as it will not penetrate walls or ceilings. At a distance of about 10 feet (3 m) the pattern is about 8 inches (20 cm) in diameter from a standard rifle, which is about the maximum effective range. Special smoothbore shotguns, such as Marlin's Garden Gun can produce effective patterns out to 15 or 20 yards using .22 WMR shotshells, which hold 1/8 oz. of #11 or #12 shot contained in a plastic capsule.

Shotshells will not feed reliably in some magazine fed firearms, due to the unusual shape of some cartridges that are crimped closed at the case mouth, and the relatively fragile plastic tips of other designs. Shotshells will also not produce sufficient power to cycle semiautomatic actions, because, unlike projectile ammunition, nothing forms to the lands and grooves of the barrel to create the pressure necessary to cycle the firearm's action.

Collectibility

Rimfire ammunition is popular with ammunition cartridge collectors, who base much of the collectibility value of rimfire cartridges on the rarity of the stamped mark on the head of the cartridge (the headstamp). There is a subcategory of collectible rimfire ammunition with headstamps commemorating certain persons who have worked in the industry, often issued in extremely small quantities on the occasion of that person's retirement. Often the majority of these cartridges are given to the retiring individual, leaving him or her to decide to whom they are traded or distributed. This increases their perceived value as collectibles.

See also

References

- ↑ Bussard, Michael (2010 )"The Impossible .22 Rimfire", American Rifleman

- ↑ "Ammo shortage is from panic buying, hoarding". TuscaloosaNews.com.

- 1 2 Frank C. Barnes (2003) [1965]. Cartridges of the World (10th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87349-605-1.

- ↑ http://5mmforums.com/the-centurion-5mm-remington-rimfire-magnum/

- ↑ Hornady .17 Mach 2

- ↑ "Hornady's New .17 Mach 2 by Chuck Hawks".

Further reading

- Suydam, Charles R. The American Cartridge: An Illustrated Study of the Rimfire Cartridge in the United States. Alhambra, Calif: Borden Pub, 1986. OCLC 26915839