Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome

| Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Patient with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | medical genetics |

| ICD-10 | Q87.2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 759.89 |

| OMIM | 180849 |

| DiseasesDB | 29344 |

| MedlinePlus | 001249 |

| eMedicine | derm/711 ped/2026 |

| MeSH | D012415 |

| GeneReviews | |

| Orphanet | 783 |

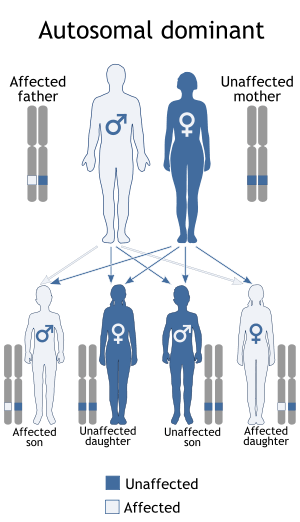

Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome (RTS), also known as broad thumb-hallux syndrome or Rubinstein syndrome,[1] is a condition characterized by short stature, moderate to severe learning difficulties, distinctive facial features, and broad thumbs and first toes.[2] Other features of the disorder vary among affected individuals. People with this condition have an increased risk of developing noncancerous and cancerous tumors, leukemia, and lymphoma. This condition is sometimes inherited as an autosomal dominant pattern and is uncommon, many times it occurs as a de novo (not inherited) occurrence, it occurs in an estimated 1 in 125,000-300,000 births.

Features of Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome

A case was described in 1957 by Michail, Matsoukas and Theodorou.[3] In 1963, Jack Herbert Rubinstein (1925–2006) and Hooshang Taybi (1919–2006) described a larger series of cases.[4]

Typical features of the disorder include:

- Broad thumbs and broad first toes

- Mental disability

- Small height, bone growth, small head

- Cryptorchidism in males

- Unusual facies involving the eyes, nose, and palate

- Anesthesia may be dangerous in these patients: “According to the medical literature, in some cases, individuals with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome may have complications (e.g., respiratory distress and/or irregular heart beats [cardiac arrythmias]) associated with a certain muscle relaxant (succinlycholine) and certain anesthesia. Any situations requiring the administration of anesthesia or succinlycholine (e.g., surgical procedures) should be closely monitored by skilled professionals (anesthesiologists or Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists, CRNA's).”[5] Primary literature suggests the children may have a higher rate of cardiac physical and conduction abnormalities which may cause unexpected results with cardioactive medications.[6] A further editorial reply in the British Journal of Anaesthesia discusses changes in the face and airway structure making it more difficult to secure the airway under anaesthesia, however, complications appeared in a minority of cases, and routine methods of airway control in the operating room appears to be successful. They recommended close individual evaluation of Rubinstein–Taybi patients for anaesthetic plans.[7]

A 2009 study found that children with RTS were more likely to be overweight and to have a short attention span, motor stereotypies, and poor coordination, and hypothesized that the identified CREBBP gene impaired motor skills learning.[8] Other research has shown a link with long-term memory (LTM) deficit.[9][10] See also Epigenetics in learning and memory.

Genetics

Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome is a microdeletion syndrome involving chromosomal segment 16p13.3 and is characterized by mutations in the CREBBP gene.[11][12] The CREBBP gene makes a protein that helps control the activity of many other genes. The protein, called CREB-binding protein, plays an important role in regulating cell growth and division and is essential for normal fetal development. If one copy of the CREBBP gene is deleted or mutated, cells make only half of the normal amount of CREB binding protein. A reduction in the amount of this protein disrupts normal development before and after birth, leading to the signs and symptoms of Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome.

Mutations in the EP300 gene are responsible for a small percentage of cases of Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. These mutations result in the loss of one copy of the gene in each cell, which reduces the amount of p300 protein by half. Some mutations lead to the production of a very short, nonfunctional version of the p300 protein, while others prevent one copy of the gene from making any protein at all. Although researchers do not know how a reduction in the amount of p300 protein leads to the specific features of Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome, it is clear that the loss of one copy of the EP300 gene disrupts normal development.

1 out of 100,000 to 125,000 children are born with RTS.

See also

References

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome -180849

- ↑ Petrij, F; Dauwerse, HG; Blough, RI; Giles, RH; van der Smagt, JJ; Wallerstein, R; Maaswinkel-Mooy, PD; van Karnebeek, CD; van Ommen, GJ; van Haeringen, A; Rubinstein, JH; Saal, HM; Hennekam, RC; Peters, DJ; Breuning, MH (March 2000). "Diagnostic analysis of the Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome: five cosmids should be used for microdeletion detection and low number of protein truncating mutations.". Journal of Medical Genetics. 37 (3): 168–76. doi:10.1136/jmg.37.3.168. PMC 1734540

. PMID 10699051.

. PMID 10699051. - ↑ Michail J, Matsoukas J, Theodorou S (1957). "Pouce bot arqué en forte abduction-extension et autres symptômes concomitants" [Arched, clubbed thumb in strong abduction-extension & other concomitant symptoms]. Revue De Chirurgie Orthopédique Et Réparatrice De L'appareil Moteur (in French). 43 (2): 142–6. PMID 13466652.

- ↑ Rubinstein JH, Taybi H (June 1963). "Broad thumbs and toes and facial abnormalities. A possible mental retardation syndrome". Am. J. Dis. Child. 105: 588–608. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1963.02080040590010. PMID 13983033.

- ↑ http://www.rubinstein-taybi.org/anesthesia.html[]

- ↑ Stirt JA (July 1981). "Anesthetic problems in Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 60 (7): 534–6. doi:10.1213/00000539-198107000-00016. PMID 7195672.

- ↑ Dearlove OR, Perkins R (March 2003). "Anaesthesia in an adult with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 90 (3): 399–400; author reply 399–400. doi:10.1093/bja/aeg537. PMID 12594162.

- ↑ Galéra C, Taupiac E, Fraisse S, et al. (2009). "Socio-behavioral sharacteristics of children with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome". J Autism Dev Disord. 39 (9): 1252–1260. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0733-4. PMID 19350377.

- ↑ Bourtchouladze R, Lidge R, Catapano R, et al. (September 2003). "A mouse model of Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome: defective long-term memory is ameliorated by inhibitors of phosphodiesterase 4". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (18): 10518–22. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10010518B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1834280100. JSTOR 3147748. PMC 193593

. PMID 12930888.

. PMID 12930888. - ↑ Alarcón JM, Malleret G, Touzani K, et al. (June 2004). "Chromatin acetylation, memory, and LTP are impaired in CBP+/- mice: a model for the cognitive deficit in Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome and its amelioration". Neuron. 42 (6): 947–59. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.021. PMID 15207239.

- ↑ Wójcik, C; Volz, K; Ranola, M; Kitch, K; Karim, T; O'Neil, J; Smith, J; Torres-Martinez, W (February 2010). "Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome associated with Chiari type I malformation caused by a large 16p13.3 microdeletion: a contiguous gene syndrome?". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 152A (2): 479–83. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.33303. PMID 20101707.

- ↑ Petrij F, Giles RH, Dauwerse HG, et al. (July 1995). "Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome caused by mutations in the transcriptional co-activator CBP". Nature. 376 (6538): 348–51. Bibcode:1995Natur.376..348P. doi:10.1038/376348a0. PMID 7630403.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome. |

- RTS – Rubinstein–Taybi Syndrome – Associazione italiana RTS

- RTS – Rubinstein–Taybi Syndrome – a site devoted to the families and people diagnosed with Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome.

- RTS – Rubinstein–Taybi Syndrome Argentina – RTS Argentina – www.rubinsteintaybi.com.ar – Grupo de Apoyo – Historias.

- Dutch RTS-site – RTS the Netherlands

- History of RTS by J.H. Rubinstein.

- GeneReview/UW/NIH entry on Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome

- Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome due to 16p13.3 microdeletion on ORPHAnet