Ryukyu independence movement

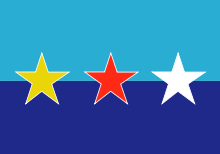

The Ryukyu independence movement (琉球独立運動 Ryūkyū Dokuritsu Undō) or Republic of the Ryukyus (Japanese: 琉球共和国, Kyūjitai: 琉球共和國, Hepburn: Ryūkyū Kyōwakoku) is a movement for the independence of Okinawa and the surrounding islands (Ryukyu Islands), from Japan. The movement emerged in 1945, after the end of the Pacific War. Some Ryukyuan people felt, as the Allied Occupation began, that the Ryukyus (Okinawa) should eventually become an independent state, instead of being returned to Japan. The majority pushed for unification with the mainland, hoping that this would hasten the end of the Allied occupation there. The islands were returned to Japan on May 15, 1972 as the Okinawa Prefecture. The US-Japan Security Treaty signed in 1952 provides for the continuation of the American military presence in Japan, and the United States continues to maintain a heavy military presence on Okinawa Island after reunification with Japan. This set the stage for renewed political movement for Ryukyuan independence.

Historical context

Initially, the Ryukyu Kingdom was a tributary state of China in East-Asia. Kings of Ryukyu sent envoys and paid a tribute to China (Ming Dynasty and Qing Dynasty). This custom began from 1372 during the Ming Dynasty and lasted until a few years before the downfall of the kingdom in 1879. After the Japanese feudal domain of Satsuma invaded Ryukyu in 1609, the kingdom was forced to send a tribute to Satsuma. Eventually Ryukyu was annexed by the Empire of Japan and transformed into Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. Some nobles resisted the annexation and a few came to China as refugees.

Similarly, there may have been significant movements for Okinawan independence following its annexation, in the period prior to and during World War II. Following the war, the United States Occupation government took over control of Okinawa. The Americans retained control over the Ryukyu Islands until 1972, twenty years after the formal occupation of the rest of Japan had ended. There was pressure in 1945, immediately following the war, for the creation of a fully independent Ryukyuan state, while later in the Occupation period there arose a strong movement not for independence but for a return to Japanese sovereignty.

Since 1972, and the return of Okinawa to Japanese control, voices turned once again towards the aim of a fully independent Ryukyuan state.

Motives and ideology

Among those who sought a return to Japanese sovereignty, there was a basic belief that the people of Okinawa were a part of the Japanese people, whether ethnically, culturally, or politically. During the Meiji period, when the Ryukyu Kingdom was formally abolished and annexed, there was a strong push for assimilation; the Meiji government, and other cultural and intellectual agents, sought to make the people of the new prefecture see themselves as "Japanese." Ryūkyūans were given Japanese citizenship, names, passports, and other official representations of their status as part of the Japanese people. They were also incorporated into the newly founded national public education system. Through this education system and other methods, both governmental and independent, Ryukyuans, along with minorities from all parts of the Empire, were gradually integrated into the Japanese people. There was a significant reimagining of the histories of Ryukyu and of Ezo, which was annexed at the same time, and an insistence that the non-Japonic Ainu of Hokkaidō and the Japonic Ryukyuan people were Japanese, ethnically and culturally, going back many centuries, despite originally having significantly different cultures. With time these reimagined identities took hold in the younger generations. They were born in Okinawa Prefecture, as Japanese citizens, and saw themselves as belonging there.

This does not mean that the independent identities have been completely lost. Many Ryukyuan people see themselves as a separate Ryukyuan people, ethnically different, with a unique and separate cultural heritage. They see a great difference between themselves and the "mainland" Japanese, and many feel a strong connection to Ryukyuan traditional culture and the pre-1609 history of independence. There is strong criticism of the Meiji government's assimilation policies and ideological agenda.

Recent events

Though there are pressures in the US and Japan, as well as in Okinawa, for the removal of US troops and military bases from Okinawa, there have thus far been only partial and gradual movements in that direction. The plan to move Marine Corps Air Station Futenma from a heavily populated area to Henoko in the north of the island (relatively less populated) was approved by Okinawa's governor in 2014,[1] despite opposition from the local population. The current governor of the prefecture, Takeshi Onaga, opposes the decision.

| Okinawa | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 24.9% | 23.9% | 20.6% |

| No | 58.7% | 65.4% | 64.7% |

| Follow resident's decision | 2.8% | 1.7% | 0.8% |

| etc. | 13.6% | 9.1% | 13.0% |

In 1995, a decision to remove troops from Okinawa was reversed, and there was a renewed surge in the Ryukyu Independence Movement. In 2005, British-Chinese Lim John Chuan-tiong (林泉忠), the associate professor of the University of the Ryukyus, conducted a telephone poll of Okinawans over 18. He obtained useful replies from 1029 people. Asked whether they considered themselved Okinawan (沖縄人), Japanese (日本人), or both, the answers were 40.6%, 21.3%, and 36.5% respectively. When asked whether Okinawa should become independent if the Japanese government allowed (or did not allow) Okinawa to freely decide its future, 24.9% replied Okinawa should become independent with permission, and 20.5% in case of no permission from the Japanese government. Those who believed Okinawa should not declare independence were 58.7% and 57.4% respectively.[3][4]

In 2013, a Chinese scholar published a paper on a state-run newspaper challenging the ownership of the Ryukyus, sparking protests in Japan.[5] Some Okinawans are studying independence.[6][7][8] The People's Daily stated that the "Chinese people shall support Ryukyu's independence."[9][10]

See also

- Ryukyu Kingdom

- Ethnic issues in Japan

- Independence movement

- Kariyushi Club (The former Ryukyu Independent Party)

- Ryukyuan people

- Ryukyuan languages

- Ainu people

- Ainu independence movement (a.k.a. Ainu-Moshiri Republic, アイヌモシリ共和国)

- Yamato people

- Gwangbokjeol (Korean independence from Japan)

- Retrocession Day (Taiwanese independence from Japan)

- Active autonomist and secessionist movements in Japan

References

- ↑ "Okinawa governor approves plan to reclaim Henoko for U.S. base transfer - AJW by The Asahi Shimbun". Ajw.asahi.com. Retrieved 2014-06-08.

- ↑ 沖縄アイデンティティとは何か~そのⅡ: 過去と未来~ [What is the Okinawa's identity ~ the second: the past and the future ~] (PDF) (in Japanese). Archives of Okinawa Prefecture. 2008-07-02. Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- ↑ Okinawa Times, January 1, 2006. The scan is from the Okinawa Independent Party website.

- ↑ "Survey on Okinawan resident identities", From the Latest Questionnaires.

- ↑ "Japan angered by China's claim to all of Okinawa | Asia | DW.DE | 10.05.2013". DW.DE. Retrieved 2014-06-08.

- ↑ http://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2013/05/18/editorials/alleviate-okinawas-burden/

- ↑ TSUKASA KIMURA/ Staff Writer. "Okinawans form group to study independence from Japan - AJW by The Asahi Shimbun". Ajw.asahi.com. Retrieved 2014-06-08.

- ↑ JSTApr 28, 2013 (2013-04-28). "Sovereignty Anniversary a Day of Celebration, or Humiliation? - Japan Real Time - WSJ". Blogs.wsj.com. Retrieved 2014-06-08.

- ↑ "China supports Ryukyu independence organisation."

- ↑ In Okinawa, Talk of Break From Japan Turns Serious

External links

- (Japanese) The Ryukyu Independent Party official website

- (Japanese) Okinawa Autonomous Workshop

- (English) (Japanese) The Okinawa Independence Movement Underground head office

- The Unofficial Constitution of the Republic of the Ryukyus

- Ōhara Institute for Social Research, Hōsei University