Saddle (landform)

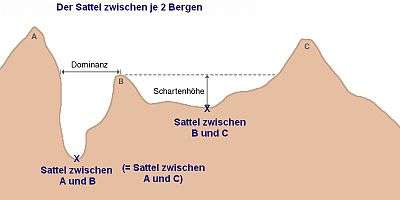

A cross-section diagram of three hills, with two saddles marked by X.

• There are three peaks (Schartenhöhe) or prominences shown labeled 'A', 'B', & 'C'.

• The diagram illustrates the topographic isolation (German: Dominanz)-the distance from a prominence which is also a minimum to the point of the same height.

• The 'isolation' (German: Dominanz) of the right two peaks is not labeled, but is represented by the dashed line.

• 'sattel zwischen' literally means saddle between so the labeling is saying the Saddle between A and C is the same saddle as between A and B

| Saddle elements in the Topography sub-discipline of Mathematics | |

|---|---|

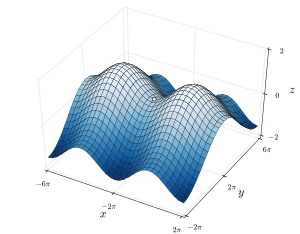

Saddle point between two hills (the intersection of the figure-eight -contour) |

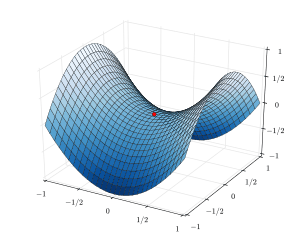

A saddle point on the graph of the surface defined by the equation: z=x2−y2 (Saddle Point shown in red) |

The saddle between two hills (or mountains) is the region surrounding the highest point of the lowest point on the line (tracing the drainage divide, the Col) connecting the peaks. When, and if, the saddle is navigable, even if only on foot, the saddle of a (optimal) pass between the two massifs, is the area generally found around the lowest route on which one could pass between the two summits, which includes that point which is a mathematically when graphed a relative high along one axis, and a relative low in the athwart axis, simultaneously; that point being by definition the Col of the saddle.

Mathematical Saddles

In mathematics, a saddle point is a point in the domain of a function where the slopes (derivitives) of orthoganal function components defining the surface become zero (a stationary point) but are not a local extremum on both axes. The saddle point will always occur at a relative minima along one axial direction (between peaks) and where the crossing axis is a relative maxima.

The name derives from the fact that the prototypical example in two dimensions is a surface that curves up in one direction, and curves down in a different direction, resembling a riding saddle or a mountain pass between two peaks forming a landform saddle. In terms of contour lines, a saddle point in two dimensions gives rise to a contour graph or trace that appears to intersect itself—such conceptually might form a 'figure eight' around both peaks; assuming the contour graph is at the very 'specific altitude' of the saddle point in three dimensions.

Structural geology

In structural geology a saddle is a depression located along the axial trend of an anticline.[1] This is not to be confused with a col which is typically a geomorphologic feature seen in landforms.

In plain language, a saddle is the lowest area between two highlands (prominences or peaks) but has two wings which span the divide (the line between the two prominences) by crossing the divide at an angle, so is concurrently the local highpoint of the land surface which falls off in the down direction. That is, the drainage divide is a ridge along the high point of the saddle, as well as between the two peaks so defines the major reference axis. A saddle can vary from a sharp narrow gap to a broad comfortable sway-backed shallow valley so long as it is both the high point in the sloping faces descending to lower elevations and the low area between the two (or three or four.[lower-alpha 1]) flanking summits. Concurrently, along a different axis, it is the low point between two peaks, so is the likely 'optimal' high point in a pass if the saddle is traversed by a track, road or railway.

|

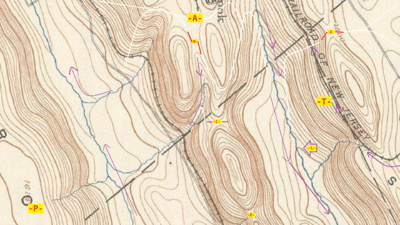

(Click for full screen image) • The map has been annotated with Purple arrows illustrating DOWN slopes for those unfamiliar with reading Topographic maps. Note the watercourses cut into the slopes creating a succession of Vee shaped notches. One of many places where this is shown is the arrow marked -L-. [lower-alpha 2] • There are white 'trails' illustrating how one might walk pushing a cart—some of these take a shallow angle across the terrain, a Traverse as does the railroad labeled with -T-. This diagram is labeled to illustrate a variety of landforms in a natural terrain setting. • The points -A-, -B-, -C-, -D- and, -E- all represent Saddles-relative minimums oriented to two or more nearby peaks, but a local maxima relative to lower (low land places) one might wish to go or come from. • The center-bottom point -E looms over two very steep slopes, so is unlikely to be used as a pass, save for mountaineers, and certainly not for transportation infrastructure. This makes it easy to classify as a Col, a non-pass, but still a saddle. [lower-alpha 3] • Toward the bottom left is -P' with an elevation annotation—these illustrate how the USGS denotes a prominence (peaks, and usually the highest on a ridgeline) on a map. | ||

Road beds, Cols and placements

Note, a road bed through a pass need not be through a Col (so will then have to be along a traverse face of one peak or the other, and the road bed will be cutting across the divide at nearly ninety degrees), but by not encompassing the Col, mathematically requires the road bed be above the altitude of the Col.

Notes

- ↑ See the center image point '-C-' in the topographical map image.

- ↑ Two of these valleys, or ravines show their respective stream's down flow in opposite directions on either side of the centered ridgeline's landforms.

A subtle thing, but when and where this occurs, the two watercourse either are the same stream and loop around the end of the mountain, or the ridge above is a 'drainage divide', and in North America the two streams are said to be in different watersheds. They have different outlets, perhaps thousands of miles apart. (The two sides of these peaks shown drain either to the Chesapeake Bay or to the Delaware River estuarys hundreds of miles apart.) - ↑ • -C- is a tougher case, for while its slopes are very steep, they might just possibly also be usable as a pass on a traversing climb. Such fine points are a matter of scale, and may rely upon field experience.

References

- ↑ "Glossary of Structural Geology". Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ↑ Whittow, John (1984). Dictionary of Physical Geography. London: Penguin, 1984, p. 464. ISBN 0-14-051094-X.

- ↑ Soanes, Catherine and Stevenson, Angus (ed.) (2005). Oxford Dictionary of English, 2nd Ed., revised, Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York, p. ISBN 978-0-19-861057-1.

- ↑ Monkhouse, FJ (1965). A Dictionary of Geography, 2nd edn.

- ↑ Chambers 21st Century Dictionary, Allied.