Salmon cannery

A salmon cannery is a factory that commercially cans salmon. It is a fish processing industry that became established on the Pacific coast of North America during the nineteenth century, and subsequently expanded to other parts of the world that had easy access to salmon.

Background

The "father of canning" is the Frenchman Nicolas Appert. In 1795, he began experimenting with ways to preserve foodstuffs, placing food in sealed glass jars and then placing the jars in boiling water.[1] During the first years of the Napoleonic Wars, the French government offered a 12,000-franc prize to anyone who could devise a cheap and effective method of preserving large amounts of food. The larger armies of the period required increased and regular supplies of quality food. Appert submitted his invention and won the prize in January 1810. The reason for lack of spoilage was unknown at the time, since it would be another 50 years before Louis Pasteur demonstrated the role of microbes in food spoilage. However, glass containers presented challenges for transportation. Shortly after, the British inventor and merchant Peter Durand patented his own method, this time in a tin can, creating the modern-day process of canning foods.[2]

Canning was used in the 1830s in Scotland to keep fish fresh until it could be marketed. By the 1840s, salmon was being canned in Maine and New Brunswick.[3] The commercial salmon canneries had their main origins in California, and in the northwest of the US, particularly on the Columbia River. They were never important on the US Atlantic Coast, but by the 1940s, the principal canneries had shifted to Alaska.[4]

North America

Native Americans

Long before the appearance of Europeans, Native Americans operated a dried salmon industry from the Columbia River, trading salmon to the plains tribes.[4] The Native Americans usually captured salmon by manually hauling seine nets (dragnets). The nets were woven with spruce root fibers or wild grass, and used sticks made of cedar as floats and stones as weights. The movement of the sticks during seining helped keep the fish together. The technique was to "sweep nets during ebb tide from upstream to down, with the net anchored at the beach upstream. A boat then carried the net out and around salmon migrating upstream."[5]

.png)

Settlers

Prior to canning, fish were salted to preserve them. Cobb claims that at the start of the 19th century, the Russians marketed salted salmon caught in Alaska in St. Petersburg.[4][6] Shortly after, the Northwest Fur Company started marketing salted salmon from the Columbia River. It then merged with the Hudson's Bay Company, and the salmon was marketed in Australia, China, Hawaii, Japan and the eastern United States. Later, some salmon salteries were converted to salmon canneries.[4]

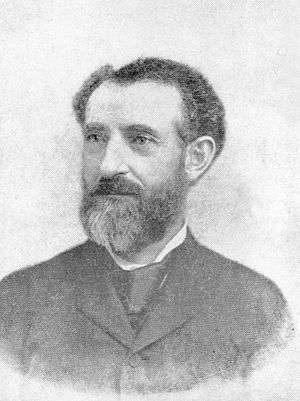

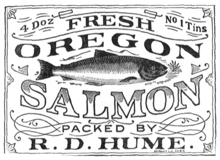

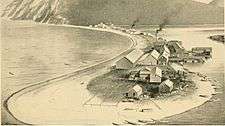

The first industrial scale salmon cannery in North America was established in 1864 on a barge in the Sacramento River by the four Hume brothers together with their partner Andrew S. Hapgood.[7] In 1866 the Hume brothers relocated the business to a site 50 miles inland on the Columbia River.[7] The history of North American salmon canneries is exemplified by their history on the Columbia River. Within a few years each of the Hume brothers had their own cannery. By 1872, Robert Hume was operating a number of canneries, bringing in Chinese people willing to work for low wages to do the cannery work, and having local Native American people do the fishing. By 1883, the salmon canneries had become the major industry on the Columbia River, with 1,700 gillnet boats supplying 39 canneries with 15,000 tonnes of salmon annually, mainly Chinook.[7]

The settlers learned the use of seine nets from Native Americans. By 1895 there were eighty-four seines on the Columbia, and Robert Hume started hauling them with teams of horses. The seines were operated from day break to dawn around islands and along beaches. At Puget Sound salmon were caught by fishing boats using purse seine nets. Purse seine nets are used to encircle a school of salmon and then trap them by drawing ("pursing") the bottom of the net together, as you would with a string purse. By 1905 the boats used engines for hauling the seine lines. In 1922 it was made illegal to use salmon purse seiners on and around the Columbia. In 1948, horse and manual seines were also outlawed.[5]

By 1889 the Chinook runs were declining, and the canneries started processing the less sought after steelhead and sockeye salmon, followed by coho and chum salmon. The number of salmon continued to decline because the canneries intercepted them before they could spawn in the upper river. The decline was accelerated by mining and forestry operations, and the introduction of grazing animals, which resulted in the spawning grounds becoming silted and polluted. Further aggravation resulted from the diversion of water for irrigation. Columbia salmon harvest managers responded to these declines by introducing the hatchery production of fish fry. As a result, production leveled and remained fairly stable for some decades, before going into a further steady decline from 1930. The Columbia's last major cannery closed in 1980.[7]

In 1928, in an attempt to measure the escapement of salmon in the south east of Alaska, the Bureau of Fisheries constructed four special weirs designed so the passing salmon could be counted (see photo below). Escapement is the proportion of spawning stock which survives fishing pressure during a salmon run. The counting stations were intended to provide harvest managers with data they needed to manage the salmon fisheries, but they missed much of the escapement. Smaller fish passed through the weirs uncounted, the salmon could not be counted during times of flood, and there were hundreds of other salmon streams in the area without counting stations.[8]

.jpg)

Timeline

- 1795–1810: Nicolas Appert works out how to preserve food in sealed jars and wins a 12,000-franc prize

- 1810: Peter Durand patents his more robust method of using tin cans, instead of breakable jars

- 1824: First recorded time salmon is canned, in Aberdeen, Scotland [4]

- 1839: Salmon first canned at Saint John, New Brunswick [4]

- 1864: First commercial salmon cannery is established on a barge in the Sacramento River [7]

- 1866: The cannery is relocated to the Columbia River, where it triggers an important industry [4][7]

- 1878: The industry spreads to Alaska, with a cannery on the Prince of Wales Island[4]

- 1890: Commercial scale operations start in northern Japan [4]

- 1906: Siberia establishes its salmon canning industry [4]

- 1936: International production peaks at about 300 thousand tonnes for the year [4]

- 1980: The Columbia River's last major cannery closes

Historical images

| Images |

|---|

Fishing for the cannery    Cannery processing   .png)  Cannery buildings     |

See also

- Alaska Packers' Association

- Alaska salmon fishery

- Alaskeros, salmon workers in Alaska

- Canned fish

- Canned sardines

- Cannery Row

- Columbia River Indigenous peoples

- History of fishing

- List of canneries

- List of canneries in British Columbia

- List of salmon canneries and communities

- List of seafood companies

- Rogue River Commercial fishing

- USS LCI(L)-1091

Notes

- ↑ Lance Day, Ian McNeil, ed. (1996). Biographical Dictionary of the History of Technology. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-19399-0.

- ↑ Klooster, John W (2009) Icons of invention: the makers of the modern world from Gutenberg to Gates p. 103, ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-34745-0.

- ↑ Newell, 1990, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Jarvis ND (1988) Curing and Canning of Fishery Products: A History Marine Fisheries Review, 50 (4): 180–185.

- 1 2 Smith, Courtland L Seine fishing Oregon Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ↑ Cobb JN (1917) Pacific salmon fisheries. Government Printing Office, Bur. Fish., Doc 1092. 297 pages.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Columbia River History: Canneries Northwest Power and Conservation Council. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ↑ Arnold, David F (2008) The fishermen's frontier: people and salmon in Southeast Alaska Page 81. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98788-0.

- ↑ Kaserman,Rebecca and René Horst (2008) "Aleuts in American Society: 1867-1941" Appalachian State University.

References

- Blyth, Gladys Young (2006) Salmon Canneries: British Columbia North Coast Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-2562-1.

- Budd, Robert and Imbert Orchard (2010) "Voices of British Columbia: Stories from Our Frontier" Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978-1-55365-463-6.

- Campbell, K. Mack (2004) Cannery Village: Company Town Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-0965-2.

- Crutchfield JA, Pontecorvo G (1969) The Pacific salmon fisheries: a study of irrational conservation. Johns Hopkins Press.

- Friday, Chris (1994) Organizing Asian American labor: the Pacific Coast canned-salmon industry, 1870-1942 Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-56639-139-9.

- Hume RD (1904) "The first salmon cannery". Pacific Fisherman Yearbook, 2 (1): 19–21.

- Muszyńska, Alicja (1996) Cheap wage labour: race and gender in the fisheries of British Columbia McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-1376-1.

- Newell, Dianne (1990) The Development of the Pacific salmon-canning industry: a grown man's game McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-0717-3.

- Radke AC and Radke BS (2002) Pacific American Fisheries, Inc: history of a Washington State Salmon Packing Company, 1890-1966 McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1185-6.

- Sisk, John (2005) "The Southeastern Alaska Salmon Industry: Historical Overview and Current Status" Southeast Alaska Conservation Assessment.., Chapter 9.5.

- Smith, Courtland L (1979) Salmon fishers of the Columbia Oregon State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87071-313-2.

- Yesaki M, Steves H and Steves K (2005) Steveston Cannery Row: an illustrated history Mitsuo. ISBN 978-0-9683807-1-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salmon canneries. |

|

|

- "A Brief Overview of the History of Fish Culture and its Relation to Fisheries Science" Gary D. Sharp, Center for Climate/Ocean Resources Study, Monterey.

- Cannery Workers and Their Unions, from the Waterfront Workers History Project.