Scottish sword dances

Performance of sword dances in the folklore of Scotland is recorded from as early as the 15th century.

Related customs are found in the Welsh and English Morris dance, in Austria, Germany, Flanders, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Romania.

- In Gillie Callum or "Scottish sword dance" the dancer crosses two swords on the ground in an "X" shape, dances around and within the 4 quarters of it.

- The Highland Fling involves a fast dance steps atop a targe

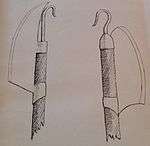

- The Dirk dance involves either one or two dancers, each holding a single Dirk.[1][2]

History of the Scottish sword dance

As a part of the traditional Scottish intangible heritage, the performance of the Sword Dance has been recorded as early as the 15th century. It is normally recognised as the war dance with some ceremonial sense in the Scottish Royal court during that period. The old kings and clan chiefs organised the Highland Games as a method to choose their best men at arms, and the discipline required to perform the Highland dances allowed men to demonstrate their strength, stamina, and agility. The earliest reference also mentioned that the dance is often accompanied with the music of bagpipes. The basic rule requires the dancer to cross two swords on the ground in an "X" shape and to dance around and within the 4 quarters of it.[3]

The earliest reference to these dances in Scotland is mentioned in the Scotichronicon, compiled in Scotland by Walter Bower in the 1440s. The passage regards Alexander III and his second marriage to the French lady Yolande de Dreux at Jedburgh in Roxburghshire on 14 October 1285.

At the head of this procession were the skilled musicians with many sorts of pipe music including the wailing music of bagpipes, and behind them others splendidly performing a war-dance with intricate weaving in and out. Bringing up the rear was a figure regarding whom it was difficult to decide whether it was a man or an apparition. It seemed to glide like a ghost rather than walk on feet. When it looked as if he would disappear from everyone's sight, the whole frenzied procession halted, the song died away, the music faded, and the dancing contingent froze suddenly and unexpectedly.

In 1573 Scottish mercenaries are said to have performed a Scottish Sword dance before the Swedish King, John III, at a banquet held in Stockholm Castle. The dance, "a natural feature of the festivities," was used as part of a plot to assassinate the King, where the conspirators were able to bare their weapons without arousing suspicion. Fortunately for the King, at the decisive moment the agreed signal was never given.

"Sword dance and Hieland Dances" were included at a reception for Anne of Denmark at Edinburgh in 1589 and a mixture of sword dance and acrobatics was performed before James VI in 1617 [4] and again for Charles I in 1633, by the Incorporation of Skinners and Glovers of Perth,

His Majesty’s chair being set upon the wall next to the Water of Tay whereupon was a floating stage of timber clad about with birks, upon the which for His Majesty’s welcome and entry thirteen of our brethren of this calling of Glovers with green caps, silver strings, red ribbons, white shoes and bells upon their legs, shearing rapiers in their hands and all other abulzements, danced our sword dance with many difficult knots and allapallajesse, five being under and five above upon their shoulders, three of them dancing through their feet and about them, drinking wine and breaking glasses. Which (God be praised) was acted and done without hurt or skaith to any.

Types of sword dance

Many of the Highland dances now lost were once performed with traditional weapons that included the Lochaber axe, the broadsword, a combination of targe and dirk, and the flail.

The old Skye dancing song, Bualidh mi u an sa chean (Buailidh mi thu anns a' cheann "I will break your head"), may indicate some form of weapon play to music, 'breaking the head' was the winning blow in cudgelling matches throughout Britain, "for the moment that blood runs an inch anywhere above the eyebrow, the old gamester to whom it belongs is beaten, and has to stop."

A combative sword dance called the Highland Dirk Dance still exists and is often linked to the sword dance or dances called "Macinorsair" (Mac an Fhòrsair), the "Broad Sword Exercise" or the "Bruicheath" (Battle Dance). These dances are mentioned in a number of sources, and may have been performed in a variety of different forms, by two performers in a duelling form and as a solo routine.

Dance with Highland Regiments

Regimental Tradition

This tradition was gradually kept in the Highlander Regiments with some changing rules. To prepare for the Sword Dance, a soldier should lay two swords on the ground in the form of an X. He would then proceed to dance a complex series of steps and movements between and around the swords to the sound of the bagpipes. The dance itself can be performed with more than one individual. This tradition of exhibition and competitive dancing carried on into the 21st century. It was performed at a Regimental Highland Games C1930s. Four swords are laid on the dance floor in a cross shape. The dancer then performs a number of intricate dance steps across and around the sword blades, keeping their backs straight, arms raised, and hands in a particular shape. Throughout the decades, this style of dance became an integral part of the performance of the pipes and drums band when it went on tour to various countries around the world. Highland country dancing (often a less formal style of dance) was also encouraged within the Regiment.[5]

Actually, the weapon in the traditional sword dance is not only the basket-hilted broadsword. In the book “Highland and Traditional Scottish Dances”, Mr. MacLellan has mentioned when his father was living on Loch Fyneside in Argyll, designed the Foursome Dance over swords as a counter to the Lochaber Dance, which was initially danced over Lochaber axes. The Broadsword indicated the basket-hilted sword worn by officers of Highland Regiments and sometimes miscalled the Claymore, which is a large two-handed weapon. The original version of the Broadswords Dance is described in Mr. MacLellan’s book, and the steps, four strathspey and one quick –time, and drill for marching on and off a dancing stage are simpler and less elaborate than those seen in some present day forms of the dance. It is not an “Old Thyme” dance and that it is not Regimental in origin.[6]

The influence of the Dance in Highland Regiments

Due to the popularity, it encouraged the recovery of traditional prestige on influence in Highland Dancing culture and competition. It increased more training and intensive preparation, or students amongst students attending the Piping Course in Edinburgh, or schoolboys from Queen Victoria School performing at the Royal Tournament in London and the Festival Tattoo in Edinburgh, due to the Highland Dancing interest.To inspire schoolboys to join the events, the school provided special instruction of Highland Dancing. In the south of England, highland and Scottish country dancing caused a wave of enthusiasm to sweep over the Service Establishments. Many officers of Highland Brigade supported the dancing, and it was taught at the Joint Service Staff College, the Army Staff College, the Royal Navy College, and the Royal Military Academy. The only “fortress” holding out against this Scottish “investment” is the R.A.F. Staff College.

The Highland dancers of Regimental Headquarter---Sgt.Oliver, Cpls,Yule and Eliott and Pte.Ferguson---gained notable successes at the Games at Oban on 15th September. The Regimental Foursome won the Alasdair Maclean Challenge Cup for Regimental Reel Dancing, beating the Gordon Highlanders’ and the Highlander Light Infantry Foursomes. Cpl.Yule won the Poltalloch Cup, presented by Colonel George Malcolm, for the non-professional dancer serving in the Armed Forces who obtained the highest aggregate of marks in the four individual dancing competitions. This was the first year of competition for the Cup.[7]

The Scottish Official Board of Highland Dancing has published its Manual on the technique and performance of the traditional Highland dances, individual and foursome. This is a comprehensive guide, with helpful illustrations of the correct basic positions, movements, and steps, and correct performance of the dances. The organisation and conduct of competitions in Highland dancing are also dealt with within the book, which is being accepted as “authoritative” by Scottish Command. The book fills a long-felt want and, though not yet established in the hearts of all Highland dancing “professors” and organisers, is being welcomed far and wide by Scottish Societies and Communities seeking guidance on dancing in the traditional style.

The Regimental Piping and Dancing Society

A Society has been formed to stimulate interest in the playing of the Highland Bagpipe, to create enthusiasm for Highland Dancing, and so raise the level of performance of both these arts in the units of the Regiment. The aims of the Society are:-- A. To assist in the training of pipers and Highland dancers generally in the Regiment, and to watch their progress throughout their Regimental career. B. To standardise settings for pipe music throughout the Regiment. C. To assist pipe presidents in all ways possible in their duties, both technical and administrative, in order to maintain the highest standard of piping and dancing in the Regiment. D. To train judges in piping and dancing for the benefit of Regimental and National competition. A Regimental Committee, representative of all the Battalions of the Regiment, is required to develop the policy of the Society.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ http://dirkdance.tripod.com/id1.html

- ↑ Traditional Step-Dancing in Scotland, by J. F. & T. M. Flett

- ↑ "Highland Dancing". Retrieved 2016-08-15.

- ↑ (New Statistical Account of Scotland Edinb. 1845 x, pp. 44-45)

- ↑ The Thin Red Line Regimental Magazine of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. UK. 1947. p. 31.

- ↑ The Thin Red Line Regimental Magazine of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. UK. 1951. p. 51.

- ↑ The Thin Red Line Regimental Magazine of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. UK. 1955. line feed character in

|title=at position 67 (help) - ↑ The Thin Red Line Regimental Magazine of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. UK. 1956. p. 64.