Battle of Taku Forts (1859)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Second Battle of Taku Forts was an Anglo-French attack against the Taku Forts along the Hai River in Tianjin, China, in June 1859 during the Second Opium War. A chartered American steamship arrived on scene and assisted the French and British in their attempted suppression of the forts.

Background

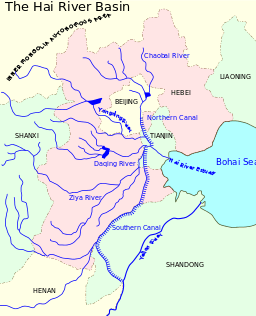

Taku is a village near the mouth of the Pei-ho River, which flows between low, muddy banks and runs into the Gulf of Pe-cho-li. Thirty-four miles above the river is Tientsin, constructed at the fork of the Pei-ho with the Grand Canal. Tientsin is the port of Peking and a place of much commerce. Peking is the capital of China and is about eighty miles above Tientsin. In the year 1858, French and British forces had battled their way to Tientsin, passing the Taku Forts at the Pei-ho's mouth with little difficulty, the works were insufficiently armed and held by a weak garrison which put up little defense. When Tientsin was occupied, the Chinese sued for peace, thus the first period of the war ended and a treaty was signed there containing among other stipulations, an agreement that the envoys of British and France were to be received at Peking within a year, and that the treaty was to be ratified there. Now the Chinese, as soon as the allies withdrew from Tientsin, began to regret having consented to allow the foreign ambassadors to enter their capital and attempted to have it arranged so that the treaty would be ratified elsewhere.

The United Kingdom and France insisted on the original agreement and the envoys of the two countries arrived off the mouth of the Pei-ho in June 1859 and announced their intention of proceeding up the river to Peking. A British fleet, under the command of Admiral James Hope, escorted them for protection against the Chinese fortifications. They had learned that they might be opposed, so prepared themselves.[4]:507

It was found that not only had the forts at the river mouth, which had easily been silenced the year before, been put into a state of repair, also, the river was blocked for stopping anything larger than rowing boats by a series of strong metal barriers. The Admiral was informed that these had been placed on the river to keep out pirates and it was promised by the Chinese government that they would be removed. Despite the promise, the local Mandarins began to start work on strengthening the defences of the river. On June 21, Admiral Hope sent the Quig commander, Hang Foo, a letter warning him that if the obstructions were not cleared out of the channel of the Pei-ho by the evening of the 24, he would remove them by force. Three days of peace passed and the Chinese failed to remove their defenses so the Anglo-French fleet began to prepare for battle.

The Engineers in the fleet surveyed the defences and watched a junk lowering an iron stake into the river, the base was three spiked legs, on top of the legs was a 25 feet (7.6 m) spike with an angled spiked arm pointing forward. At high water, this spike would be a few feet below water. The spikes were positioned so that they could pierce through the hull of a ship coming up the river at high tide. [4]:507 Beyond the spikes could be seen a barrier of logs fixed together to form cylinders, 24 feet (7.3 m) long, a cable passed through the centre of each cylinder and they were used to float two chains, run from bank to bank, below the water level.[4]:507

Hope had several powerful ships in his squadron, none of these could take a direct part in the coming fight though. This was due to the entrance of the Pei-ho, which was obstructed by a wide stretch of shallows, the depth of water on the bar being only two feet at low tide, and a little more than eleven at high tide. Because of this, the British could only rely on eleven steam powered gunboats for the actual fight against the Chinese forts. The Royal Navy gunboats were small wooden steamers of light draft built during the Crimean War for service in the shallow waters of the Baltic and Black Seas.

Admiral Hope crossed the bar with his eleven boats and anchored below the forts on the June 23. The gunboats were; HMS Plover, HMS Banterer, HMS Forester, HMS Haughty, HMS Janus, HMS Kestrel, HMS Lee, HMS Opossum and HMS Starling all of four guns apiece. HMS Nimrod and HMS Cormorant, both of six guns, were also present. Each of the gunboats had a crew of around fifty or sixty officers and men, so that the eleven small steamers together brought forty-eight guns and 500 men into the battle. The more heavily armed steamers, outside the sand bar, were to offload another 500 or 600 men, marines and sailors via steam launches, boats and an unknown number of junks. This force was meant to be used as a landing party to attack the forts once they had been silenced.

A French frigate, the Duhalya, was also on the scene but was too large to engage in the battle. Her crew would participate in the final land engagement. None of the Britons expected that the ensuing battle would prove a difficult task. The Taku Forts consisted of many structures, a big Chinese fort on the south side protected the coast, with earthen ramparts stretching nearly half a mile long, and guard towers behind them. At the other end of the complex sat another large fortress on the north bank of the river, many other smaller forts sat in between the two larger forts. Though the British believed that only a small Quig garrison held the defences, this due to a previous bombardment and attack in which the British and French successfully captured the positions. After this engagement it was found that hundreds of artillery pieces protected the forts with hundreds of Qing Army troops.

Battle

Naval engagement

On the evening of June 24, no answer having been received from the Quig commander, Rear Admiral Hope announced that the attack would be made next day and after dark the Admiral sent in one of his officers, Captain George Willes, and a few enlisted men to examine the obstacles in the river and see what he could do to remove them. Three armed launches, filled with explosives, accompanied Captain Willes. Rowing up quietly under cover of the darkness, Willes discovered the row of iron stakes. The first barrier was just opposite the lower side of the big South Fort as it was called. After passing cautiously between two of the spikes, the British sailors rowed up the river for a quarter of a mile when they came to a second barrier. The barrier was a heavy cable of cocao fibre and two chain cables, all strewn across the channel, twelve feet apart and supported at every thirty feet by a floating boom, securely anchored up and down the river's flow. Two of the British boats were left to place a mine under the middle of the second floating barrier. Captain Willes pushed on farther into the darkness, headed for a third obstacle in the Pei-ho of two huge rafts, moored as to leave only a narrow channel in middle of the waterway, this passage was also defended with large iron spikes.

Willes got out on one of the rafts and got on hands and knees and after investigating the situation, Willes decided that mere ramming with a gunboat's prow would not be enough to displace the barricade. As he lay on the raft he could see the Chinese sentries on the riverbank, but was unseen by them. Returning to his boat, he rode the Pei-ho's current back down to the second barrier. By this time the mine was ready and once the fuse was lit, the Britons pulled down the stream to the main flotilla. The resulting explosion revealed the Briton's presence to a Chinese artillery battery who proceeded with firing a few cannon shots from the South Fort but the cannon balls missed. The small expedition was regarded as a complete success; despite Willes failure to destroy two of the three barriers. Before the next morning the Chinese had repaired the space blown clear by the mine, thus rendering Willes mission as pointless. On Saturday morning, June 25, reportedly a bright and hot day, the gunboat flotilla cleared for action. Admiral Hope’s orders were that nine of the ships should anchor close to the first barrier and bring their guns to bear on the forts, while the two others break through the barriers and clear the way for a further advance.

High tide came at 11:30 am, and it was intended that all of the gunboats would be in position by that time. However, the difficulty of moving so many ships in a narrow channel no more than 200 yards wide, with a strong current and with mud banks covered by shallow water on each side, moving gunboats through the channel proved to be a great risk and it was not long before Banterer and Starling were aground. During all of the initial maneuvers, the Chinese forts had not shown any sign of life. Their embrasures were closed; a few black flags flew on the upper works, not a single soldier was seen on the mud ramparts. Plover, with all steam and Admiral Hope aboard, was close to the first barrier of iron spikes with Opossum, now commanded by Captain Willes. The task of Opossum was to destroy the first obstacle. At 2:00 pm upon a signal from the Rear Admiral, Opossum attached a cable, passed it over one of her winches, reversed her engines, and tried rip the spike up and out of the river bottom. It was so well emplaced that it was half an hour of work, to remove two obstacles and place buoys to mark the opening.[4]:508 The British commander in Plover now steamed through the gap opened by Opossum, followed in succession by other gun boats.

The two little gun boats approached the floating barrier. It was at this point the Chinese in the South Fort opened fire from a leftmost rampart. Immediately along the walls of all the forts; banners were raised on every flag pole, embrasures were opened and guns pushed out. From about 600 yards away on the leftmost rampart and from the front of the North Fort, the Chinese artillery rapidly fired amazingly accurate cannon shots, aimed at the leading ships. General Hope Grant's signal came, "Engage the enemy," flew from the masthead of Plover; her four guns opened, three of them on the big fort to the left. Two hundred yards off, the other gun responded to the North Fort. After the other ten gunboats received the signal, they anchored and began to open fire on the Chinese positions.[4]:508 The battle was a close quarters gunnery action, the Chinese fire, instead of slackening from British return fire, seemed to have grown fiercer. The British later reported that when one gun and crew were killed by their fire, another gun and crew would quickly filling the embrasure. Chinese troops fired so steadily and aimed that for years afterwards many of the British veterans believed that trained European artillerymen were actually firing the Chinese gun batteries. After less than twenty minutes, Plover had thirty-one killed or wounded out of a forty-man crew.

Her commander, Lieutenant Rason, was cut in half by a round shot; James Hope was wounded in the thigh but refused to leave the deck and Captain McKenna, who was attached to his staff, was killed while at Hope's side. Only nine unwounded men were left on board, but they, with the help of some of their fellow wounded crew, kept two of the guns in action. They fought on a deck covered with blood and bits of splintered wood. Around this time the American steamer Toey-Wan of the Pacific Squadron arrived and anchored outside the bar. Commodore Josiah Tattnall of the United States Navy was on board, and he went to Plover, under fire from the Chinese guns, to offer assistance to the British. Commodore Tattnall, a veteran of the War of 1812, put aside his mistrust of the British and justified his presence by stating "blood is thicker than water", a now famous saying. The United States government, as a neutral power, did not order any American vessels to proceed in this attack. Tattnall offered to send in his steam launch to help evacuate the dead and wounded from danger, an offer which was gratefully accepted by the Britons. When Tattnall left Rear Admiral Hope for Powhatan in his launch, he was forced to wait a moment at Plover's port side for his men who had come aboard with the Commodore. A moment later a few men returned, covered in black powder marks and sweaty from excitement.

The American Commodore asked, "What have you been doing, you rascals?" "Don’t you know we're neutrals" "Beg pardon, sir," said one of the men, "but they were a bit short-handed with the bow-gun, and we thought it no harm to give them a hand while we were waiting." At 3:00 pm, James Hope ordered Plover, now nearly destroyed, to drop down the river to a safer station, and he transferred his flag to Opossum. A few minutes later, a round shot crashed through Opossum's rigging close to the Admiral, knocking him down and breaking three of his ribs; a bandage was fastened around his chest and he was seated on the deck of the gunboat where he still kept his command. Later on he even insisted on being lifted into its barge in order to visit and encourage the crews of Haughty and Lee. "Opossum, ahoy!" called an officer from Haughty, "Your stern is on fire." "Can't help it", shouted back Opossum's commander. "Can’t spare men to put it out. Have only enough to keep our guns going." After this Opossum was apparently relieved and gave up the fight for a while to steam down to the first barrier. Lee and Haughty now bore the brunt of the engagement, they suffered severely. Everything on the two gunboat's decks was turned into scraps from Chinese fire and Lee was hit well in several places at and below the water line.

Woods, her boatswain, informed her commander, Lieutenant Jones, that unless holes in his hull could be plugged Lee would sink, as her pumps and engine could not get the water out as fast as it was rushing in. "Well, then, we must sink," said the lieutenant; "you cant get at the worst of the holes from inside, and I'm not going to order a man to go over the side with the tide running down like this, and our propeller going." Woods replied by promptly volunteering to go over the side and see what he could do. His commander warned him that the screw must be kept going, or the ship would drift out of place. Besides the possibility of drowning, Woods would risk being killed by the propeller blades; but Woods, went over the side anyway, with a line around his waist and with a few plugs and rags in his hands. when Woods dove in he was almost swept up by the screw several times. Fortunately for him, he was capable of escaping the screw and successfully plugged several shot-holes. All of this became unnecessary though because Lee continued to fill up with river water and had to give up her place in the fight to run aground, preventing her sinking. Cormorant which was now the flagship, replaced the grounded Lee. Plover, after severe damage was sunk just after Admiral Hope transferred to the other gunboat. Hope suffered from fainting at some point so his doctors persuaded him to send himself to one of the three steamships on the other side of the bar. Captain Shadwell, the next senior officer, then took command of the attacking fleet. At 5:30 pm and after three hours of fighting, Kestrel sank at her anchors. Of the eleven gunboats, six were sunk, disabled or put out of action.

Land engagement

The fire of the Chinese forts was slackening though and at 6:30 pm, after a rushed meeting aboard Cormorant, it was resolved to commence with a land attack of marines and sailors who had been waiting in small boats and inside the bar. Their objective was to capture the South Fort by means of a frontal assault. The time was after 7:00 pm and very little daylight was left for the landing party, when the boats were towed in by Opossum, Toey Wan and one of the armed steamships, being used by the American Commodore.

Captain Shadwell took command of the landing party, which was made up of sailors under Captain Vansittart, and Commanders Heath and Commerell. Sixty French sailors, under a Commander Tricault, of Duhalya accompanied Captain Shadwell. The marines were under Colonel Lemon and a party of engineers and sappers with ladders for scaling walls. As the boats pulled into the shore, the fire from the North Fort had ceased, and only an occasional shot was fired from the long rampart of the South fort. The landing zone area was 500 yards (460 m) in front of the rightmost bastion of the South Fort, below the stakes. The tide had fallen so far that it was not possible to get very near to the actual shore, this made the landing of almost 1,200 men more difficult than it could have been if the tide was still high. The column of land forces had to make its way across 500 yards (460 m) to 600 yards (550 m) of mud, weeds, and small pools of water, the ground was reportedly so soft in places that a man could sink to his waist if they step in the wrong spot.[4]:509 As soon as the men of the first landing boat stepped ashore, the entire front of the South Fort responded with a large salvo of cannon fire. The silence of the Chinese guns was obviously a ruse meant to lure the British and French into making a land attack. The plan of the Chinese worked perfectly. Once hearing the sounds of the South Fort, the gunboats resumed fire until the land force began their advance on the fort.

The Chinese gunners concentrated their cannons, swivel guns and rockets on the landing party. As the Britons and French came within range, Chinese riflemen and archers opened upon them from a crowded crest of the South Fort's rampart. As the Anglo-French shore party struggled onwards, round shot, grape shot and balls from the Chinese swivel guns, muskets, rockets and arrows, fell among the allies in showers according to survivors. It was very hard to return the fire as many rifles were full of mud and their ammunition was wet.[4]:509 Captain Shadwell was one of the first men wounded; Vansittart fell, with one leg wounded by a musket ball. Dozens of dead and wounded lay on the field. The wounded had to be carried back to the boats to save them from sinking in the mud. Three broad ditches lay between the landing zone and the fort. No more than 150 men reached the second of these and only fifty advanced to the third which was just below the Chinese rampart. The British and French ammunition cartridges were nearly all useless from moist terrain, and had only one scaling ladder by the time they reached the wall. The ladder was raised against the rampart, and ten men were climbing up it when a volley of small arms fire from above killed three men and wounded five others.

The ladder was then thrown back by the Chinese and broken. The British and French were forced to retreat to their boats after facing firm resistance. At 10:00 pm the wounded were sent back to the boats.[4]:510 The sky was dark but was kept lit by the Chinese who burnt blue lights and launched rockets and fireballs at the retiring French and Britons. After this the battle was over. Sixty-eight men were killed in the land attack and nearly 300 wounded. Twelve of the dead were Frenchmen, along with twenty-three of the wounded, the French commander was also wounded. Eighty-one Britons in total died as result of the fighting with a total of 345 wounded. Sometime during the battle, an American launch, evacuating wounded and with Commodore Josiah Tattnall on board, was attacked by Chinese batteries, one American sailor was killed and one other was slightly wounded, the Commodore was unharmed. Several of the landing boats had been sunk while waiting on the river bank during the land battle. When the Anglo-French force retreated, many had to wait in the water till they could be extracted. At 1:00 am on June 26, the last men of the landing party re-embarked their ships. The remaining gunboats retreated down to the bar. Another shore party was sent in later that morning, their mission was to blow up or burn the grounded gunboats that could not be freed and were in threat of being captured by the Chinese, whether this mission was completed or not is not known, though two of the grounded gunboats are said to have been re-floated. Chinese strength and casualties are unknown.

Aftermath

The battle on the Pei-ho river ended. The disaster put an end to further attempts to reach Peking.

The course of events was analysed, previous battles against the Chinese had been easily won and this may had led to underestimating the enemy. The stakes and barrier, apart from stopping the gun boats simply sailing past the forts had done little damage. The reduction in fire from the fort leading to the decision to send in the land force was a trick that the Allied force fell for. Making the land assault at low tide, leaving the troops to wallow exhausted in the mud would have been avoided if the attack had been made at high tide, when the small boats could have landed the troops almost under the fort walls.[4]:510

Within the next year an allied force of British and French troops, under General Sir James Hope Grant and General de Montauban, launched an expedition. This engagement led to the 1860 Third Battle of Taku Forts in which the allies were successful, opening the route to Peking. The Second Opium War ended soon after.

References

- 1 2 3 Janin, Hunt (1999). The India-China Opium Trade in the Nineteenth Century. McFarland. p. 126–127. ISBN 0-7864-0715-8.

- 1 2 3 4 The Second Battle of the Taku Forts (第二次大沽口之战) Archived September 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Raugh, Harold E. (2004). The Victorians at War, 1815-1914: An Encyclopedia of British Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 100. ISBN 1-57607-925-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

Sources

- Bartlett, Beatrice S. Monarchs and Ministers: The Grand Council in Mid-Ch'ing China, 1723–1820. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1991.

- Ebrey, Patricia. Chinese Civilization: A Sourcebook. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993.

- Elliott, Mark C. "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies." Journal of Asian Studies 59 (2000): 603-46.

- Faure, David. Emperor and Ancestor: State and Lineage in South China. 2007.