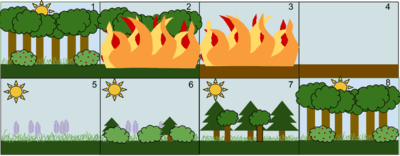

Secondary succession

1. A community

2. A disturbance, a fire, destroys the forest

3. The fire burns the forest to the ground

4. The fire leaves behind empty, but not destroyed soil

5. Grasses and other herbaceous plants grow back first

6. Small bushes and trees begin to colonize the public area

7. Fast growing evergreen trees and bamboo trees develop to their fullest, while shade-tolerant trees develop in the understory

8. The short-lived and shade intolerant evergreen trees die as the larger deciduous trees overtop them. The ecosystem is now back to a similar state to where it began.

Secondary succession is one of the two types of ecological succession of plant life. As opposed to the first, primary succession, secondary succession is a process started by an event (e.g. forest fire, harvesting, hurricane) that reduces an already established ecosystem (e.g. a forest or a wheat field) to a smaller population of species, and as such secondary succession occurs on preexisting soil whereas primary succession usually occurs in a place lacking soil.

Simply put, secondary succession is the ecological succession that occurs after the initial succession has been disrupted and some plants and animals still exist. It is usually faster than primary succession as:

- Soil is already present, so there is no need for pioneer species;

- Seeds, roots and underground vegetative organs of plants may still survive in the soil.

Mechanism

Many mechanisms can trigger succession of the second including facilitation such as trophic interaction, initial composition, and competition-colonization trade-offs.[1] The factors that control the increase in abundance of a species during succession may be determined mainly by seed production and dispersal, micro climate; landscape structure (habitat patch size and distance to outside seed sources);[1] Bulk density, pH, soil texture (sand and clay).[2]

Vegetation

Imperata grasslands are caused by human activities such as logging, forest clearing for shifting cultivation, agriculture and grazing, and also by frequent fires. The latter is a frequent result of human interference.[3] However, when not maintained by frequent fires and human disturbances, they regenerate naturally and speedily to secondary young forest. The time of succession in Imperata grassland (for example in Samboja Lestari area), Imperata cylindrica has the highest coverage but it becomes less dominant from the fourth year onwards. While Imperata decreases, the percentage of shrubs and young trees clearly increases with time. In the burned plots, Melastoma malabathricum, Eupatorium inulaefolium, Ficus sp., and Vitex pinnata. strongly increase with the age of regeneration, but these species are commonly found in the secondary forest.[4]

Soil

Soil properties change during secondary succession in Imperata grassland area. The effects of secondary succession on soil are strongest in the A-horizon (0–10 cm), where an increase in carbon stock, N, and C/N ratio, and a decrease in bulk density and pH are observed. Soil carbon stocks also increase upon secondary succession from Imperata grassland to secondary forest.[5]

Post-fire succession

Soil

Generation of carbonates from burnt plant material following fire disturbance causes an initial increase in soil pH that can affect the rate of secondary succession, as well as what types of organisms will be able to thrive. Soil composition prior to fire disturbance also influences secondary succession, both in rate and type of dominant species growth. For example, high sand concentration was found to increase the chances of primary Pteridium over Imperata growth in Imperata grassland. [6] The byproducts of combustion have been shown to affect secondary succession by soil microorganisms. For example, certain fungal species such as Trichoderma polysporum and Penicillium janthinellum have a significantly decreased success rate in spore germination within fire-affected areas, reducing their ability to recolonize.[7]

Vegetation

Vegetation structure is affected by fire. In some types of ecosystems this creates a process of renewal. Following a fire, early successional species disperse and establish first. This is then followed by late successional species. Species that are fire intolerant are those that are more flammable and are desolated by fire. More tolerant species are able to survive or disperse in the event of fire. The occurrence of fire leads to the establishment of deadwood and snags in forests. This creates habitat and resources for a variety of species. Fire can act as a seed dispersing stimulant. Many species require fire events to reproduce, disperse, and establish. For example, the knobcone pine ("Pinus attenuata") has closed cones that open for dispersal when exposed to heat caused by forest fires. This particular conifer grows in clusters because of this limited method of seed dispersal. A tough fire resistant outer bark and lack of low branches help the knobcone pine survive fire with minimal damage.[8]

References

- 1 2 Cook, W.M., Yao, J., Forster, B.L., Holt, R.D., Patricks, L.B., 2005. Secondary succession in an experimentally fragmented landscape: Community pattern across space and time. Ecology, 86: 1267-1279

- ↑ Van der Kamp, J., Yassir, I., Buurman, P., 2009. Soil carbon changes upon secondary succession in Imperata grasslands (East Kalimantan, Indonesia). Geoderma, 149: 76-83

- ↑ MacKinnon, K., Hatta, G., Halim, H., Mangalik, A., 1996. Ecology of Kalimantan. The ecology of Indonesia Seri Vol. III

- ↑ Yassir, I., Van der Kamp, J., Buurman, P., 2010. Secondary succession after fire in Imperata grasslands of East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 137: 172-182

- ↑ Van der Kamp, J., Yassir, I., Buurman, P., 2009. Soil carbon changes upon secondary succession in Imperata grasslands (East Kalimantan, Indonesia). Geoderma, 149: 76-83

- ↑ Yassir, I. (15 April 2010). "Secondary succession after fire in Imperata grasslands of East Kalimantan, Indonesia". Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 137: 172-182. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2010.02.001.

- ↑ Widden, P. (March 1975). "The effects of a forest fire on soil microfungi". Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 7 (2): 125–138. doi:10.1016/0038-0717(75)90010-3.

- ↑ Burczyk, Jaroslaw; Adams, W. T.; Shimizu, Jarbas Y. (3 October 1996). "Mating patterns and pollen dispersal in a natural knobcone pine (Pinus attenuata Lemmon.) stand". Heredity. 77: 251,260. Retrieved 27 May 2016.